“Forever Young”: Digital De-Aging, Memory, and Nostalgia

Kathleen Loock / Europa-Universität Flensburg

Digital de-aging, the process of making actors appear younger on screen than they actually are, is becoming the new normal in Hollywood. After first experimentations with computer-generated youthfulness in a flashback scene of X-Men: The Last Stand (Ratner) in 2006, and—already much more refined—in 2008’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Fincher), TRON: Legacy (Kosinski), which was released in 2010, had 60-year-old actor Jeff Bridges play opposite his digitally rejuvenated self, who looked like the 32-year-old Bridges from 1982’s TRON (Lisberger). Having an older character interact with his younger self in this manner pushed the boundaries of digital de-aging, which has since further advanced and become an increasingly more convincing and, overall, more common visual effect in Hollywood cinema. From Orlando Bloom as unaging elf Legolas in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (Jackson, 2013) to Michael Douglas’s Hank Pym in Ant-Man (Reed, 2015) and Ant-Man and the Wasp (Reed, 2018), from Robert Downey Jr., who plays a young version of Tony Stark in Captain America: Civil War (Russo & Russo, 2016), to the de-aged Kurt Russell in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (Gunn, 2017), Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (Rønning & Sandberg, 2017), and Colin Firth in Kingsman: The Golden Circle (Vaughn, 2017)—(mostly male) actors are getting a digital facelift that erases their real age and chronology.

The practice has finally become so prevalent that 2019 has variously been called “a monumental year for de-aging in film” (Kemp), “a year haunted by the digital phantoms of movie stars as they once looked” (Dowd), and the year when “Hollywood has become unstuck in time” (Breznican). A total of six blockbusters—Captain Marvel (Boden & Fleck), Avengers: Endgame (Russo & Russo), It Chapter Two (Muschietti), Gemini Man (Lee), Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker (Abrams), and The Irishman (Scorsese)—de-aged their stars with the help of visual effects companies like Lola VFX, Weta Digital, and Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). These companies have perfected their different techniques over the last few years, which involve “digital cosmetics” to smooth out wrinkles and remove blemishes with patches, blurs, glows, and digital paint, as well as tracking markers, scans, CGI models, performance capture technology, and reference material from past performances that is combined with the new footage. Considering the digitally edited faces of Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci in The Irishman, director Martin Scorsese expressed worries about what he calls the “youthification” of actors he has known and worked with all his life (Rose). Digital de-aging is supposed to be an invisible effect in the service of unprecedented realism. But, as Scorsese’s misgivings and many critics’ voices show, it still remains a controversial filmmaking tool and one, I argue, that enters into competition with memory and nostalgia for the past.

To be sure, the increasingly realist aesthetic of digital de-aging has been lauded as a breakthrough for visual effects technology and storytelling. It has proven to solve problems with the rules about time and time travel in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and made it possible to realize the science-fiction premises of movies like TRON: Legacy, Terminator: Genisys (Taylor, 2015), and Gemini Man, where time warps and cloning drive the plots, as well as decades-spanning epics such as The Irishman, that center on the long-term development of (aging) characters, without layers of make-up, prosthetics, or casting different (i.e., younger) actors in the same roles. Advocates of the practice have pointed out how de-aging supports the suspension of disbelief as it allows filmmakers to create less disruptive links between the past and the present. “Youthified” actors have also commented on how de-aging might impact the longevity of their careers. In The Irishman: In Conversation, the Netflix special feature that has Scorsese, De Niro, Pacino, and Pesci talking about the production of The Irishman, De Niro weighs in on the de-aging technology, predicting that, “We’ll all be able to act for another 30 years.” At a screening of Gemini Man, Will Smith joked about the future use of his data and how he will no longer need to stay in shape: “There’s a completely digital 23-year-old version of myself that I can make movies with now. … I’m gonna get really fat and really overweight” (King).

More skeptical observers of the trend have expressed their fears about the legal implications of digital de-aging technology and the data it amasses and about the diminishing prospects for young actors to land a breakout role. They are also worried about the gray area in which Hollywood’s de-aging efforts and inexpensive, accessible deepfake software seem to converge, arguing that “the drive to fool the viewer is the same” (King). Most notably, however, there is disagreement about whether the technology has sufficiently advanced so that de-aging does not have an “uncanny valley” effect (Masahiro). Despite the high degree of verisimilitude digitally rejuvenated faces have achieved in Hollywood, something seems to be off with “youthified” versions of familiar actors on screen that threatens to disturb audiences and cause discomfort. The uncanniness of a de-aged Will Smith or Robert De Niro can be located in the occasional weird sheen on their altered features as well as in the unnatural movements that either seem inhumanly fast and smooth (in the case of Gemini Man) or belong to an elderly, less intense actor rather than the one that digital de-aging technology has created. “You can make a seventy-something Robert De Niro look young (or at least, come somewhat close to it),” writes Vulture’s Bilge Ebiri, “but you can’t really make him act young. Especially for an audience that remembers what a young Robert De Niro did look like, and sound like, and move like.” This observation is as important as the fact that Gemini Man’s young, muscular Will Smith is nothing like the lanky, mustache-wearing Will Smith audiences know from the 1990s sitcom, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air (NBC, 1990-1996).

I suggest that there is an alienating disconnect that has ultimately less to do with the technical perfection and realist aesthetic of de-aging and more to do with the ways in which the digital doppelgänger interferes with a star’s intertextuality (i.e., the ways in which an actor’s previous films and—aging—star persona determine readings of his or her performances) and, above all, with the memories, desires, and nostalgic longings that audiences associate with a familiar actor’s actual younger self. A de-aged Will Smith or Robert De Niro, in other words, may serve Hollywood’s storytelling purposes, yet the discrepancy between what audiences recall and what they see onscreen may pose an existential threat to how people understand (and remember) themselves and the world in which they live in relation to popular culture. By following an actor’s work over many years and decades, audiences synchronize their own memories and lived experiences with movies, TV shows, and career trajectories, often with a nostalgic glance backwards that helps to construct and maintain a coherent, consistent sense of identity in the present. If digital de-aging produces “youthified” versions of familiar actors as it helps aging performers to stay “forever young,” it produces alternate realities that threaten to overwrite audience memory and eventually detract from the illusion that de-aging technology seeks to create.

Image Credits:

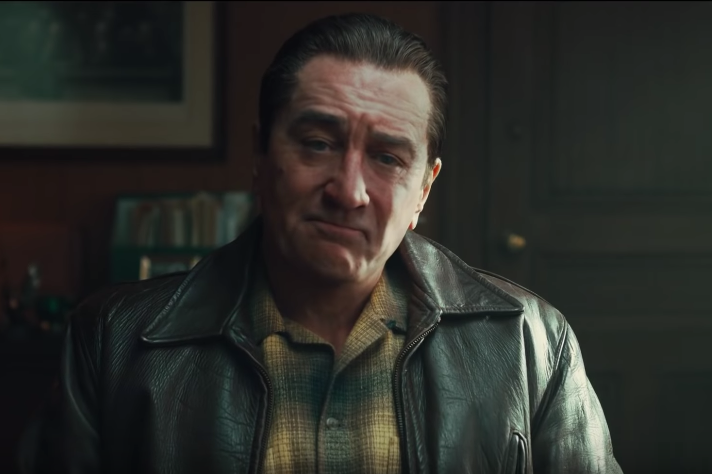

- In The Irishman, digital de-aging allowed Robert De Niro to play the same character at multiple points in his life.

- Over the past decade, digital de-aging has become increasingly more convincing and more common in Hollywood cinema, turning back the clock on (mostly male) actors.

- Martin Scorsese relied on the digital de-aging of actors Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci to tell his character-driven, decades-spanning mob epic The Irishman.

- In Gemini Man, 51-year-old Will Smith plays opposite a 23-year-old version of himself.

Breznican, Anthony. “The Irishman, Avengers: Endgame, and the De-aging Technology That Could Change Acting Forever.” Vanity Fair 9 Dec. 2019. Web. 9 Mar. 2020. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/12/the-de-aging-technology-that-could-change-acting-forever

Dowd, A. A. “Gemini Man Uses De-Aging Technology to Make a Case against De-Aging Technology.” AV Club 15 Oct. 2019 Web. 9 Mar. 2020. https://film.avclub.com/gemini-man-uses-de-aging-technology-to-make-a-case-agai-1839041610

Ebiri, Bilge. “So, How Is the De-Aging in The Irishman? Incredibly Impressive.” Vulture 27 Sept. 2019. Web. 9 Mar. 2020. https://www.vulture.com/2019/09/the-de-aging-in-the-irishman-how-bad-is-it.html

Kemp, Matt. “‘Holy Grail’ Digital Effects Rewinding the Clock for Actors.” AP News 12 Jan. 2020. Web. 9 Mar. 2020. https://apnews.com/43f8ed7e9a753c2191c9af7f4754bd6c

King, Darryn. “The Game-Changing Tech Behind Gemini Man’s ‘Young’ Will Smith.” Wired 24 Sept. 2019. Web. 9 Mar. 2020. https://www.wired.com/story/game-changing-tech-gemini-man-will-smith/

Masahiro, Mori. “The Uncanny Valley.” Trans. Karl F. MacDorman and Norri Kageki. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine (June 2012): 98-100. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6213238

Rose, Steve. “Will Hollywood’s New Youthifying Tech Keep Old Actors in Work for Ever?” The Guardian 10 June 2019. Web. 10 Mar. 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/jun/10/will-hollywoods-new-youthifying-tech-keep-old-actors-in-work-for-ever

Pingback: Convocatorias en publicaciones científicas – FACSO Educación Virtual

this is extremely so cool to watch and play

it is a great app store

watch ipl live

best information about Mini Militia Mod Apk