Over*Flow: Digital Humanity: Social Media Content Moderation and the Global Tech Workforce in the COVID-19 Era

Sarah T. Roberts / University of California, Los Angeles

Author’s Note: Over the past days, I have fielded many questions asking about commercial content moderation work during the global coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. There are many aspects to consider, including location, logistics and infrastructure, legal worker protections, and state-level actions. As I have written and rewritten this article, I have needed to repeatedly come back to update this article based on changing circumstances. At this point, the evening of March 17, I will not fundamentally change it but will continue to update it until it goes to press. My heart goes out to all of those around the world who are touched by this disease: all of us

A small gathering at UCLA last week, in what we could not know at the time was likely to be the last of its kind for most of us for the foreseeable future, a group of scholars at all levels of career and life gathered with community activists, artists and others to respond to a conversation curated by Professor Patrik Svensson under the aegis of Humane Infrastructures, an appropriate context for what we were about to collectively experience, despite assuredly not having been on the horizon during the event’s planning.

For the purposes of this event I was asked, in what I have now come to regard as an uncanny bit of timing, to discuss technology labor forces dedicated to social media content moderation and/as infrastructure, prompting me to open my remarks with a nod to “human infrastructure” more generally. It is an exercise I find useful to my work but a metaphor or description that has serious limitations. And so I use it, while also applying to it various caveats, the first of which is simply that humans are humans. They are not pipe. They are not fiber. They are not, despite all attempts of management theorists of the early 20th century and gigwork proponents of the 21st, cogs to be replaced when one becomes worn, reducible to their motion study-documented singular movements, or blips on a delivery map.

Yet because the approach to provisioning labor for large-scale technology operations often takes on these overtones, it bears discussing labor forces as infrastructure, if for no other reason than to accurately account for them in the production chain of things like, in my case, social media, or manufactured goods, or textiles, or whatever the product or output may be. I also believe that gaining insight into corporate orientations toward such labor forces is helpful to develop a more thorough and sound critique of said orientations and the concomitant practices that emerge from characterizing workforce as infrastructure in the first place. In other words, we need to see how the firms see to make the most salient and effective critiques of their practices and credos.

I will cut to the chase of what many readers want to know: how is the pandemic of COVID-19, the coronavirus that is sweeping around the globe, impacting the moderation of social media. More to the point, your question may be, “Why is corona having an impact on moderation at all?” Let me give the briefest of overviews that I can to say that the practice of social media moderation happens at industrial scale with many of the transnational service outsourcing firms now involved, and with countless other players of lesser size at the table. It is a global system that involves labor pools at great geographic and cultural distance, as well as jurisdictional and legal remove, from where we might imagine the center of social media action is: Menlo Park, or Mountain View, or Cupertino or another Silicon Valley enclave.

The second thing to bear in mind is that there is a vast human workforce doing an incredible amount of high-impact content moderation for firms; my typical estimate (that I consider to be extremely conservative) is that the global moderation workforce is in the six figures at any given time, and I likely need to try to revise this number significantly. Yes, there are AI and computational tools that also conduct this work, but it is important to keep in mind that it is exceedingly difficult for those systems to work without human oversight or in the absence of humans vetting and doing manual removals, too.

This particular fragility has been seen most acutely today at Facebook, which announced yesterday evening that it would shut down as much of its operations as it could and have workers work from home when possible. In the case of their commercial content moderators, Facebook has explained that there are many cases in which workers cannot do their work effectively from home and the company is therefore moving to a much greater reliance on its AI tools and automated moderation systems. The switch in reliance upon automated removal appears to have occurred today, when vast numbers of users began reporting the deletion of benign and sometimes even newsworthy content (in many cases, about COVID-19). Confirmed by some representatives from Facebook is that there was a “bug” with some of the automated content removal systems that has now been corrected.[1]

To understand this better, I will describe the general status quo for much of the top-tier American social media firms and their content moderation ecosystem.[2] The characteristics of the ecosystem is that it tends to be arranged with contract labor through third-party companies and has a global footprint. The firms have created their own network of call center-like facilities that form a web across the globe, and cover a massive array of linguistic, cultural, regional and other competencies and knowledge (although there are inevitable gaps and gaffes).

The distributed nature of the contract commercial content moderation system indeed allows for some degree of redundancy when it comes to issues of natural disaster or other catastrophic events that could take a center, a city or even a region offline. That said, most firms are at capacity when it comes to their screening needs, and the loss of a major site could very well impact quality. That appears to have happened in the last 72 hours, when Metro Manila and, indeed, much of the island upon which it is located, Luzon—a part of the Philippine archipelago that is home to 57 million people—went into quarantine. Reports the Singaporean Straits Times, “Police began closing off access to the Philippines’ sprawling and densely populated capital Manila, a city of some 12 million people, imposing a month-long quarantine that officials hope will curb the nation’s rising number of coronavirus cases.”

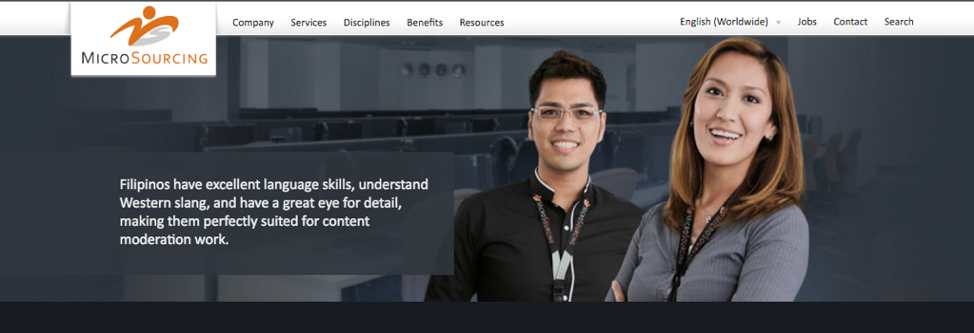

The Philippines is also the call center capital of the world, and competes with India for the vast outsourced business of commercial content moderation for the so-called Global North. In short, the Philippines is where social media content goes to be screened.

Eleven days ago, I communicated with a reporter colleague to give my sense of how a virus-related shutdown in the Philippines could affect American social media giants. I told him that while a lot of the most irritating and highest-volume unwanted content (as deemed by the platforms) can be found and removed by automated tools—here I refer to spam, pornographic content, copyright violations, and other already known-bad material—they tend to be imperfect and blunt instruments whose interventions can be calibrated to be more sophisticated or to cast a wider net.[3] But the loss of a major moderation site that would mean a switchover to reliance on these tools would invariably cause disruption in social media’s production chain, and could even potentially lead to quality issues perceived by users.

That appears to be the very case we saw today, where we see users become frustrated by false positives: cases where overzealous and undersophisticated AI tools aggressively remove reasonable content, because its judgment is too rudimentary. The alternative is also no alternative at all, for if the AI tools were turned off altogether, the result would be an unusable social media platform flooded with unbearable garbage, spam and irrelevant or disturbing content. One moderator interviewed in my book described the internet without workers like him as “a cesspool.”

Which, then, is the lesser of two evils, an overpoliced automated AI-moderated internet, or a “hole of filth” (as another Silicon Valley-based worker described it) of unbearable human self-expression? Ultimately, the firms will decide for the former, as it is powerful matter of brand protection and legal mandates (most from outside the United States) that will drive their choice in this matter. I suspect that it will be much of the public’s first contact to both the contours of content moderation on its platform, as well as how the disappearance virtually overnight of legions of humans doing this work has led to marked and immediate quality decline.

I return to the most important question, perhaps, that has been asked about this issue, which is why the work cannot simply be done by the workers from home. The answer, like everything about this issue, is complex. In many cases, such work can and is done at home. In the case of AAA social media firms, however, constraints like privacy agreements and data protection policies in various jurisdictions may preclude this. There is also a nontrivial infrastructure that goes into setting up a computing center with requisite hardware, software (internally developed and maintained systems) and routing of data. The call center locations themselves are often highly secure, with nothing allowed on the floor where workers are logged in. Working from home eliminates the ability for oversight and surveillance of workers and their practices, both what they are doing and what they are not, to the extent that can be achieved on-site. This alone is possibly a deal-breaker for moving the work home. In a moment of dark humor, one rightly cynical colleague pointed out that this is an event that, while likely wholly unimagined and unplanned, is allowing for a certain amount of stress testing of these tools at scale.

Bringing the work consisting of the rapid review of thousands of images and videos, many of which can be psychologically difficult and taxing, into the home also may be considered too much to ask of workers in a time of crisis. Workers in call centers rely on each other and their teams for support doing commercial content moderation, and may have access to an on-site or on-call therapist, counselor or other mental health professionals.[4] But it is also worth mentioning that many people already do this kind of work at home, whether as contractors or on microtask sites from anywhere in the world.[5]

Further, infrastructure differences will play into the picture locally. For example, European tech hub the Republic of Ireland has widespread penetration of at-home fixed broadband, whereas in the Philippines the story looks different. Here is where we return to the way the firms themselves view the matter of outsourced labor in what we can consider the production chain of social media: as a component in a production cycle characterized by the East to West flow of supply-chain logistics for manufactured goods. The model is one of just-in-time, in which all aspects of the process, from putting up a site to hiring in workers to the actual moderation itself, takes place as quickly and as “leanly” as possible, particularly for functions such as content moderation that are seen as a “cost center” rather than a “value-add” site of revenue generation.

Just-in-time supply-chain logistics may be being tested in other parts of the tech industry and in industries reliant on other types of manufactured products, when we consider the goods’ origin point (frequently East Asia, in general, and China, specifically, particularly for textile, tech and other material goods). Consider the recent shuttering of numerous retail chains (e.g., Apple Stores; Lululemon; Victoria’s Secret) not only as issues of lack of clientele or safety of employees, but one that may reflect a significant gap in the availability of goods making their way out of factories and across oceans: “Just how extensive the crisis is can be seen in data released by Resilinc, a supply-chain-mapping and risk-monitoring company, which shows the number of sites of industries located in the quarantined areas of China, South Korea, and Italy, and the number of items sourced from the quarantined regions of China,” reports the Harvard Business Review.

When we consider a social media production chain that is less material, perhaps, in terms of the product (user-facing content on a social media site) than an H&M fast fashion jacket or a pair of Apple AirPod Pros, the essential nature of the presence of humans in that chain is just as apparent as when a production line goes down for a month and no goods leave the factory. Here, where content moderators are both the product (in the form of their cultural and linguistic sense-making ability upon which their labor is frequently valued and sold) and the producer (in the form of the work they undertake), their impact of their loss in the production chain must be considered profound.

In essence, what is supposed to be a resilient just-in-time chain of goods and services making their way from production to retail may, in fact, be a much more fragile ecosystem in which some aspects of manufacture, parts provision, and/or labor are reliant upon a single supplier, factory, or location. Just as it is in manufacturing, where a firm discovers that a part is made only in one factory and its going offline affects everything downstream, such is it decidedly the case for the fragile ecosystem of outsourced commercial content moderation and its concentration in areas of the world such as the Philippines. The reliance on global networks of human labor is revealing cracks and fissures in a host of supply-chain ecosystems. In the case of human moderators who screen social media, their absence is likely to give many users a glimpse, quite possibly for the first time, of the digital humanity that goes into crafting a usable and relatively hospitable online place for them to be. In the face of their loss, perhaps just when we need them the most—to combat the flood of misinformation, hate speech, and racism inspired by the global pandemic that is COVID-19 now circulating online—they are gone. Will we learn to finally collectively value this aspect of the human infrastructure just a little bit more than not at all?

Image Credits:

- Facebook’s announcement on March 16th indicated to many that a new experiment in content moderation was forthcoming.

- Professor Siva Vaidhyanathan of UVA expresses frustration with Facebook’s moderation under all-AI, March 17, 2020.

- Microsourcing, a Manila-based commercial content moderation outsourcing firm, advertised their laborforce as having specialized linguistic and cultural “skills.” In this way, these “skills” were the commodity on offer. Source: Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media (Yale University Press, 2019)

- It bears mentioning that there was some debate on Twitter about whether or not this bug was related to the letting go of human content moderators, with Guy Rosen of Facebook stating that it was not and former Facebook CSO Alex Stamos expressing skepticism. My guess is that the new widespread reliance on AI tools has already revealed and will continue to reveal a variety of hits a human would not make. [↩]

- The operative phrase here is “top-tier”; many smaller firms have considerably fewer resources to put on moderation and may have devised other systems entirely to manage the bulk of their moderation needs. Two important examples of alternative systems are Reddit and Wikipedia, both of which rely on a huge network of volunteer community moderators whose interventions are user-facing and who are typically themselves close to the communities they moderate. [↩]

- See the work of Safiya U. Noble, Ruha Benjamin, Cathy O’Neill, Frank Pasquale, Joan Donovan and others who demonstrate that algorithmic interventions are deeply imbued with and shaped by a host of values, manipulation and bias, following key critiques of the politics of software by Wendy HK Chun, of computation by David Golumbia, after the fundamental question posed and answered by Langdon Winner that artifacts, indeed, have politics. [↩]

- Even when counselors are available, it is not always the panacea it may seem. Some workers contracted by Accenture discovered that what they presumed were private sessions with workplace therapists were actually reporting on those sessions to Accenture’s management, according to The Intercept. [↩]

- See this report released just yesterday on the state of microwork in Canada, from the Toronto Workforce Innovation Group (TWIG), or an interview with sociologist Antonio Casilli on microwork in France. [↩]

Pingback: 1. Trump from Michael_Novakhov (197 sites): Lawfare – Hard National Security Choices: COVID-19 and Social Media Content Moderation | Trump News

Pingback: 1. Trump from Michael_Novakhov (197 sites): Lawfare – Hard National Security Choices: COVID-19 and Social Media Content Moderation | All News And Times

Pingback: 1. Trump from Michael_Novakhov (197 sites): Lawfare – Hard National Security Choices: COVID-19 and Social Media Content Moderation | Trumpism And Trump - trumpismandtrump.com

Pingback: Trump News: 1. Trump from Michael_Novakhov (197 sites): Lawfare – Hard National Security Choices: COVID-19 and Social Media Content Moderation | Global Security Review

Pingback: Lawfare – Hard National Security Choices: COVID-19 and Social Media Content Moderation | FBI News Review Network - fbinewsreview.net

Pingback: Fin del interregno: hacia la sociedad digital post-Covid19 - EcuadorToday %

Pingback: O que há de trabalho por trás da desinformação: indicações de leitura

In the era of strong development of information technology, the demand for commercialization increases, accompanied by strict and efficient management by technology. In my opinion, that is completely reasonable and worth mentioning.