Over*Flow: Unlocking Disability: A Short Analysis of Representations of Disability in Netflix’s Locke & Key

Ryan Banfi / University of southern california

Numerous network and streaming companies failed to adapt Joe Hill’s six-book comic series, Locke & Key (2008-2013), for TV/film. The adaptation of Locke & Key for TV was first attempted by Fox in 2010. Universal Studios endeavored to produce a movie trilogy based on the graphic novels in 2014. IDW Entertainment tried to adapt Hill’s series for television in 2016. In 2017, Hulu ordered a pilot of Locke & Key, but the company later abandoned the project. In 2018, Netflix decided to produce a ten-part season of Hill’s comics. The show was available to stream on February 7th, 2020.

Adapting Locke & Key is cumbersome due to the graphic violence in the comics. The plot revolves around a demon attempting to murder the Locke family in order to obtain their magical keys. The Locke’s weapon of defense is their supernatural home, named Keyhouse, and the various enchanted keys that live there. It is axiomatic that the creators of the Netflix produced Locke & Key (2020-) show, Meredith Averill, Aron Eli Coleite, and Carlton Cuse, sacrificed the adult content of the source material for a “one size fits all” television version of the comics. On the back of volumes 2-6 of Locke & Key, a parental advisory warning near the bar code states that the comics are “Suggested for Mature Readers” (Vol. 1 is absent of this warning). The Netflix TV series is rated TV-14, a step down from what the show would have been rated, TV-MA, had the series stayed truer to the graphic novels. Any depiction of Nina Locke or Ellie Whedon being raped, or Dodge’s ruthless murders and harsh language had been scrubbed away for streaming.

Netflix’s omission of this explicit material marred the themes of disability in the show, whereas Joe Hill’s comics discussed the hardships of people with disabilities explicitly. This downplayed the importance of Rufus Whedon, a character with disabilities, in the TV program. In the comics, Rufus is the sole character who understands Dodge’s master plan to obtain the Omega Key. Because Rufus is cognitively delayed, the other characters overlook his intelligence. Rufus endures Dodge’s use of the epithet, “retard,” and Dodge’s various comments about having him locked away for his disability. All of this is proven to be “too real”[1] for a TV-14 show that is more interested in the soap opera aspect of the comics than it is with discussing the source of the horror in the graphic novels–violence towards minorities.

Netflix casted an actor with Autism named Coby Bird to play Rufus Whedon. Bird proudly displays his bio on his Instagram and his Twitter account–“I am a 17 year old actor with Autism. Rufus Whedon on Netflix’s Locke & Key. Guest Star: Speechless & The Good Doctor. Autism/Disability Advocate.” Before playing Rufus in Locke & Key, Bird guest starred as Liam West, a patient with Autism, in the show, The Good Doctor (2017-). In the episode, “22 Steps” (1.7), the hero of the show, Dr. Shaun Murphy (Freddie Highmore), treats Liam West. Dr. Murphy is a young surgeon with Autism and Savant Syndrome. The casting of Highmore to play Dr. Murphy exhibits “crip face,” which is a term that is used to describe a nondisabled person playing a character with disabilities in a show or film.

Albeit Netflix counteracts “crip face” by hiring Coby Bird for the role of Rufus, they also devalue Joe Hill’s version of the character.[2] The TV program deletes Rufus’ engagement with others who doubt his abilities. Rufus’ complex character arc–from shy guy to brave soldier–is nonexistent.

In the comic saga, Dodge imposes himself on his ex-high school girlfriend, Ellie Whedon (Rufus’ mother). While staying at the Whedon residence, Dodge continually rapes Ellie and uses magic in front of Rufus. Dodge states that he can commit sorcery while Rufus watches because Rufus “doesn’t understand” what he is seeing (Vol. 2, pg. 14). Dodge’s dismissal of Rufus is his downfall.

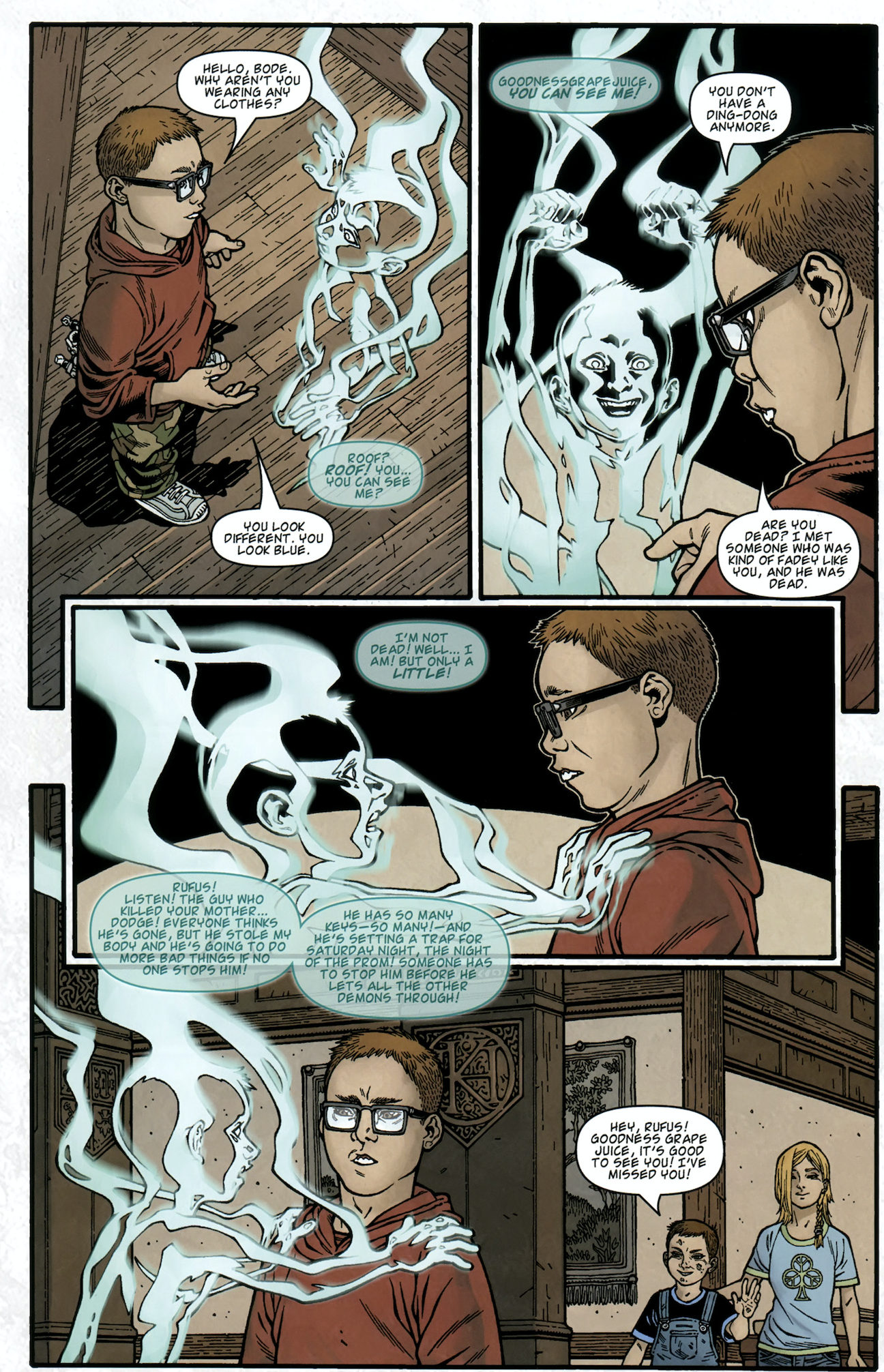

Dodge consistently refers to Rufus as a “retard” (Vol. 2, pgs. 45; 97; 98; and Vol. 6, pg. 155). However, Rufus is the most capable character in the comic book series because he “understand[s] everything” (Vol. 6, pg. 137). Rufus’ innocence allows him to see the magical keys being used, whereas adults are unable to comprehend the sorcery of the keys. Rufus is also safeguarded by the effects of the keys. For example, Dodge is unable to use the Head Key to erase Rufus’ memory because Rufus’ neck does not contain a keyhole (Vol. 2, pg. 142). Moreover, Rufus is able to see Bodie’s specter after Bodie’s body has been possessed by Dodge via the Ghost Key (Vol. 6, pg. 34). Rufus’ purity shields him from the conniving adult world. This makes him all the wiser.

Although Rufus productively protects the Locke family, the town of Lovecraft punishes him for being too competent for his disposition. After Rufus attacks the Dodge-possessed-Bodie in Vol. 6 (pg. 35), he is placed in a mental ward (Vol. 6, pg. 36). Despite the town’s dismissal of Rufus, it is Rufus who escapes from the asylum and it is he who kills Dodge by carrying him back into the wellhouse where Dodge was previously kept (Vol. 6, pg. 156).

Netflix’s Rufus is used sparingly and problematically. We first see Rufus in the opening episode, “Welcome to Matheson” (1.1). Rufus does not speak. He waves his army doll at Bodie (Jackson Robert Scott) to show a gesture of affection. A reverse shot displays Bodie mirroring Rufus’ salute. In the segment “Keeper/Trapper” (1.2), Rufus hands a bear trap to Bodie to help him capture Dodge (Laysla De Oliveira; Felix Mallard). This confirms the trope of parents’ being overly concerned about people with disabilities interacting with their children. In the episode “Echoes” (1.9), Rufus’ mother (Sherri Saum) shows Kinsey and Tyler Locke (Emilia Jones and Connor Jessup) her memories via the Head Key. Ellie’s recollection of Matheson proves to be too brutal for Rufus to see. He is left behind with Bodie. Later in this episode Rufus is knocked unconscious by Dodge. The last time we see Rufus is when he is transported to the hospital in the season finale, “Crown of Shadows” (1.10). By the end of the first season, Rufus becomes dormant.

Rufus’ TV trajectory may ring true to Coby Bird’s progression from a silent child to a fearless actor. In an interview with Yahoo News, Bird stated that as a kid he did “not have any language.” Later in the series Bird’s character becomes more verbal. Despite Rufus’ on-screen development in becoming a livelier person, his character does not prove to be as salient in assisting the Locke family defeat Dodge as he was in the comics.

The silver lining is that Netflix is hiring nonnormative actors to play characters who have disabilities. Moreover, the show does do what disability advocates such as Tom Shakespeare yearn for in TV shows: casting a person with a disability whose non-normativity is never explained.[3]

Eric Graise, a double amputee, plays Logan Calloway in Netflix’s Locke & Key. The character of Logan Calloway solely exists in the TV show. He is not in the comics. Logan is first seen keying Javi’s (Kevin Alves) car for parking in a handicap parking spot (1.2). In the segment, “Head Games” (1.3), Tyler Locke asks Logan why he is wearing shorts in the Winter. Logan responds by asking Tyler, “My legs look cold to you?”

The show never explains how Logan Calloway lost his legs. Logan’s disability never defines his character. What’s more is that Logan actively rebels against those who dismiss the struggles of people with disabilities; e.g. when he keys (an obvious pun on the show’s title) an inconsiderate asshole’s car. Logan’s humor diffuses Tyler’s anger and Logan is regarded by the other teens as a charismatic leader. While Netflix may have had issues with adapting Rufus for the screen, they succeeded in incorporating a character with a disability who maintains a productive role throughout the first season.

Coby Bird and Eric Graise are advocates for disability rights. Graise demands that the entertainment industry “hire diverse. Period. Not just in front of the camera, not just in the writer’s room, but period.” Graise never wants to be called an “inspiration.” He “struggle[s] with that.”

I am not calling Eric Graise an inspiration. But TV programs need more characters like Logan Calloway in Locke & Key for the reason that Logan’s disability is not central to his character. Logan has a real influence on the other characters. He helps them through his leadership. Whereas Rufus’ is not given the same autonomy in the show. The disability themes in the graphic novel should have been instilled in the TV adaptation of the comic series, regardless of the source material’s brutality towards nonnormative people. Netflix’s addition of Logan Calloway seems to work as Logan is not converted from one medium to another. He is a stand-alone character. Adapting characters with disabilities has proven to be problematic. Are their identities lost in the process?

Image Credits:

- Locke & Key, a Netflix original series

- Coby Bird shares a photo of himself on the set of Netflix’s Locke & Key via his Instagram

- Gabriel Rodriguez’s artwork of Rufus Whedon in the comic, Locke & Key

- Rufus Whedon speaks with Bodie Locke’s specter in the comic, Locke & Key

- Coby Bird as Rufus Whedon in Netflix’s Locke & Key

- Eric Graise showcases his dance moves

- Eric Graise as Logan Calloway in Netflix’s Locke & Key

- For an analysis of soap operas avoiding the “reality” of having disabled characters in their shows please see Cumberbatch, Guy and Negrine, Ralph. Images of Disability on Television. New York: Routledge, 1992, 81-82. [↩]

- See Paul Longmore’s foundational essay on representations of disability in media, Longmore, Paul K. “Screening Stereotypes: Images of Disabled People.” In Screening Disability: Essays on Cinema and Disability edited by Smit, Christopher R., and Enns, Anthony, 1-17. Lanham: University Press of America, Inc., 2001. [↩]

- Tom Shakespeare calls for nonnormative bodied characters to star in shows that do not primarily address their disability. On the subject of Peter Dinklage starring as Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones, Shakespeare states, “I’d like to see restricted growth actors performing in roles, like Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones, for which their height is incidental.” [↩]

Great essay! I came looking for exactly this right after finishing the season, and you’ve pretty well explained my discontent as an autistic person myself. I really wanted Rufus to have more interaction with his age group peers. Aligning this capable young man most closely with a small child isn’t exactly a good look, however nice it is that they cast Coby Bird in the role and however nice of a job he did with the role. Thanks for making this post!

Pingback: About Me | theroyaltenebaum

Whilst I enjoy the commentary on disability and the way it’s portrayed, I want to point out that an adaptation is exactly that. An adaptation. We don’t need to see the graphic rape scenes from the comics. It isn’t necessary to the story and honestly, I’m tired of people presuming that an adaptation has to be a carbon copy.

as someone dxxed autistic i disagree with this so much? whether you view it as censorship of the original comics or not, i do not need to hear an autistic person be called the r slur over and over. it adds nothing. i much rather see autistic characters just go about their lives rather than having to relive my own trauma with that word just to see someone like me on screen because people think it’s not authentic representation if the autistic person doesn’t get insulted.

I agree that leaving out some of the more violent scenes was the right choice for this series. They were unnecessary to the overall plot, and would have excluded a large audience that otherwise would have missed the enjoyment of the show. I often worry about some of the writers and adults who enjoy graphic novels for this element. As for the adaptation of the autistic character of Rufus, if this was the “key” character and purpose of the novel, I believe he should have been portrayed as such in the adaptation. It is true that you do not see enough of his character’s progression to fully understand and appreciate his role in the series. However, I do applaud Netflix’s attempt to be as inclusive as possible with its characters in a number of its series, including the inclusion of characters with disabilities and from the LGBTQ community.