Queer Female Superheroes: DC Comics Bombshells Tell Their Own Story

Christina M. Knopf / SUNY Cortland

In 2013, DC Collectibles introduced a line of statues by artist Ant Lucia called the DC Comics Bombshells, which rendered fans’ favorite female superheroes and villains in the style of pin-up models from the 1940s (see below). In 2015, writer Marguerite Bennett used Lucia’s character designs as the basis for a new, feminist, queer, comic book series DC Comics Bombshells. Bennett was praised for “low key pulling off a level of representation still largely absent in most mainstream films and TV shows.”[1] Bennett’s own female, queer identity is significant in this regard because she is not creating diversity but offering representation, noting, “I might just not know how to write anyone straight.”[2] And queer female readers appreciate seeing familiar characters in stories more specifically “for” them.[3] In the words of Bennett’s Aquawoman, “I am the teller of my own story. I belong to myself alone.”[4] DC Comics Bombshells, with its all-female starring cast, established by an all-female creative team, exemplifies the validation of women’s experiences and self-expression, offering a retro comic book variant of #MeToo — women telling women’s stories.

The series used the changing role of women during World War II as its premise. Bennett’s allohistorical universe followed the exploits of established but reimagined female superheroes, anti-heroes, and supervillains as they joined the war effort as part of a female paramilitary organization called The Bombshells. Despite their pin-up stylings, characters were defined not by their sexuality but by their wartime roles: Batwoman played for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Supergirl and Stargirl were Russian bomber pilots in the Night Witches regiment. Wonder Woman joined the Army while Aquawoman worked reconnaissance with the Navy. Zatanna was a cabaret performer in Germany and Huntress a member of the German youth underground. Catwoman and Poison Ivy were smugglers in the European black market. Harley Quinn was a doctor in a London psychiatric hospital. (See image below.) Additionally, the characters represented different sexual orientations, gender identities, colors, nations, faiths, ages, and economic backgrounds, all of which were revealed subtly through the contexts of the stories. Bennett’s writing thus managed to represent the variety of women’s experience without resorting to the comic book formula of using one or two women as archetypal stand-ins for all women.

“In this story, in this universe,” Bennett said, “I wanted the women to be the ones to define what heroism is going to be for this coming century.”[5] Therefore, the heroines exist in a world where they are not derivatives of male superheroes but are instead heroes in their own right. The allohistory was created without the real-world constraints faced by women of the past (or present). Though prejudices are found in the Bombshells universe, they do not limit the activities of the women. Bennett explained, “I don’t want to see them first have to prove that they’re allowed to be heroes. […] I wanted to move society ahead [so that] when girls pick up these books, they can see these women […] living up to their fullest potential.”[6]

The Bombshells story is a response to, and enabled by, heightened attention to contested public spaces with active debates about who is/not allowed to participate in civic life. The alternative version of WWII offers a reminder that the contributions of women in the past, and present, is often undervalued or dismissed. Commander Amanda Waller describes her Bombshells unit saying, “While the good gentlemen are relying on traditional warfare — we have engaged an independent organization that makes use of ‘unexpected and unsuspected resources’” — women (emphasis added).[7] WWII, with its apparent clarity of purpose, is a popular media frame for subsequent conflicts.[8] Bombshells thus offers a useful parable for exploring the social changes of the present day; shifting gender roles of the 1940s works as a metaphor for the shifting gender identities of the 2010s. In 1941, the workforce became gender integrated; in 2016, bathrooms did. In 1943, women were allowed to serve in all branches of the military; in 2010, gays were allowed to openly serve, and in 2016, combat jobs were opened to women.

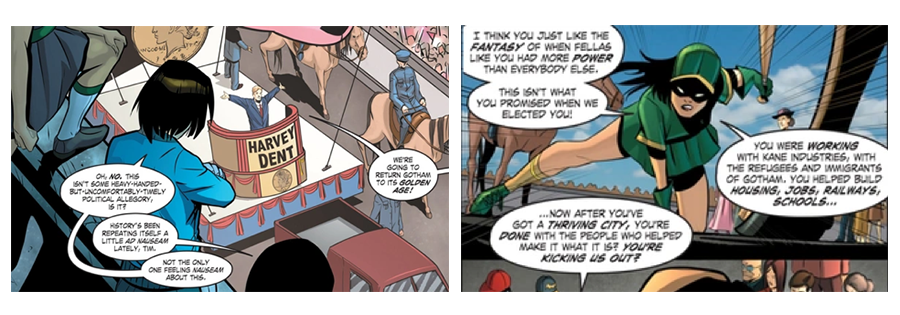

The second series of DC Comics Bombshells, “United,” was introduced in late 2017 and featured the Japanese internment camps that held over 100,000 Americans between 1942 and 1946. In 2018, immigration detention centers in the United States held about 40,000 people per day. The parallels between these institutions were introduced in April 2016 when Bennett featured the mayoral campaign of Harvey Dent, reimagined as a war-era Donald Trump. While Trump was promising to “make America great again,” Dent promised to “make Gotham golden once more.”[9] Both campaigns promoted stricter immigration as a means of improving the economy and reducing crime and civil unrest. And, both campaigns made visible the white, patriarchal hegemony of American power structures by making explicit a desire to return to an era of exclusively white male privilege (see below).[10]

It is arguably WWII’s iconicity in American cultural fabric that makes the diversity and situated truths of Bombshells narratively and commercially successful. Its historical context and vintage aesthetic work within the nostalgia economy that supports the superhero industry.[11] Authenticity was established through use of retro art styles and media formats. Each story acts as a separate chapter focusing on a different heroine, each given her own generic formula: Wonder Woman, a war film; Supergirl, a propaganda reel; Catwoman, a noir; Zatanna, a Hammer horror; Aquawoman, a romance; Harley Quinn, a comedy; and, Batwoman, a pulp radio serial.[12]

Batwoman, aka Kate Kane, was the series’ lead heroine. As a Jewish-American lesbian fighting Nazis, her identity was central and organic to the story. By comparison, the CW’s new Batwoman (2019-present) television series has been criticized for “riding the feminist train” and ostracizing “the very people who they need to keep the ratings going, 18–45-year-old males, especially white males who are the significant purchasers of comic books” by featuring a queer superhero played by a queer actress (Ruby Rose),[13] and for being a mediocre show unremarkable aside from its queerness.[14] Whereas the Bombshells Batwoman exists independently of a male counterpart, even preventing the crime that instigated the creation of Batman in canon, CW’s Batwoman is a replacement for the inexplicably-absent Batman, offering a thin foundation for what some fans have perceived as needless male-bashing in the trailer (below). Likewise, the trailer’s revelation of Kane’s sexual orientation is perceived as clunky at best.[15] The combined effect may be undermining the series’ morals about integrity and privilege.

The main message of Bennett’s Bombshells, which is also found in the CW’s Batwoman, and in the queer, Muslim, black, and Latinx characters throughout the CW Arrowverse, is captured by the words of a Bombshells Batgirl: “You’re allowed to be happy in your own skin, in your own home.”[16]

Image Credits:

- DC Collectibles Ant Lucia Art (YouTube)

- DC Comics Bombshells.

- The DC Comics Bombshells cast

- Frames from the Bombshells’ Trump allegory

- Batwoman’s Pulp Aesthetic and the Moment She Prevents the Creation of Batman

- CW’s Batwoman Trailer (YouTube)

- Riley Silverman, “Bombshells and Batwomen: An Interview with Marguerite Bennett,” SyFyWire, June 15, 2017, accessed August 23, 2019, https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/bombshells-and-batwomen-interview-marguerite-bennett. [↩]

- Quoted in Silverman, “Bombshells,” paragraph 4. [↩]

- Silverman, “Bombshells. [↩]

- Marguerite Bennett, Laura Braga, & Mirka Andolfa, DC Comics Bombshells, Volume 2: Allies (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, 2016). [↩]

- Vaneta Rogers, “DC Comics Bombshells Creates World Where Women Were Heroes of World War II,” Newsarama, July 24, 2015, accessed October 15, 2016, http://www.newsarama.com/25336-dc-bombshells-creator-creates-world-where-women-were-heroes-of-world-war-ii.html, paragraph 7. [↩]

- Quoted in Rogers, “DC Comics Bombshells,” paragraphs 11-12. [↩]

- Marguerite Bennett, Mirka Andolfo, & Laura Braga, DC Comics Bombshells, Volume 3: Uprising (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, 2017). [↩]

- Ex., Andrew Crampton, & Marcus Power, “Frames of Reference on the Geopolitical Stage: Saving Private Ryan and the Second World War/Second Gulf War Intertext,” Geopolitics 10, no. 2 (2005): 244-265. [↩]

- Bennett, Andolfo, & Braga, Uprising. [↩]

- Andrew O’Hehir, “America’s First White President, Salon, December 10, 2016, accessed January 24, 2017, http://www.salon.com/2016/12/10/americas-first-white-president/; Andrew O’Hehir, “Fake News, a Fake President and Fake Country: Welcome to America, Land of No Context,” Salon, December 3, 2016, accessed August 10, 2019, https://www.salon.com/control/2016/12/03/fake-news-a-fake-president-and-a-fake-country-welcome-to-america-land-of-no-context/. [↩]

- Carol Tilley, “Superheroes and Identity: The Roles of Nostalgia in Comic Book Culture,” in Reinventing Childhood Nostalgia: Books, Toys, and Contemporary Media Culture, ed. Elisabeth Wesseling (London: Routledge, 2018), Kindle edition, 51-65. [↩]

- Rogers, “DC Comics Bombshells,”; Barksdale, “DC Comics”; Amy Ratcliffe, Marguerite Bennett discusses WWII female heroes in ‘DC Comics Bombshells’,” Comic Book Resources, July 29, 2015, accessed October 26, 2015, from http://www.cbr.com/marguerite-bennett-discusses-wwii-female-heroes-in-dc-comics-bombshells/. [↩]

- Bobbie L. Washington, “The Batwoman Controversy,” Medium, May 21, 2019, accessed August 23, 2019, https://medium.com/@screamingbear/the-batwoman-controversy-a18c94dfb8d. [↩]

- Alex Cranz, “The Mediocrity of Batwoman also Feels Like One of Its Biggest Strengths,” Gizmodo, July 18, 2019, accessed August 23, 2019, https://io9.gizmodo.com/the-mediocrity-of-batwoman-also-feels-like-one-of-its-b-1836505759. [↩]

- Washington, “The Batwoman”; Susan Polo, “The CW’s Batwoman Pilot Gets the Most Important Thing about Batwoman Right,” Polygon, July 18, 2019, accessed August 23, 2019, https://www.polygon.com/tv/2019/7/18/20698871/cw-batwoman-review-sdcc-2019. [↩]

- Bennett, Andolfo, & Braga, Uprising. [↩]

Pingback: Tim Drake and the Evolution of Queer Representation in DC Comics