Superhero Noir: Expanding the Emotional Depth of Superhero Narratives in Jessica Jones

Katrina Margolis / University of Texas at Austin

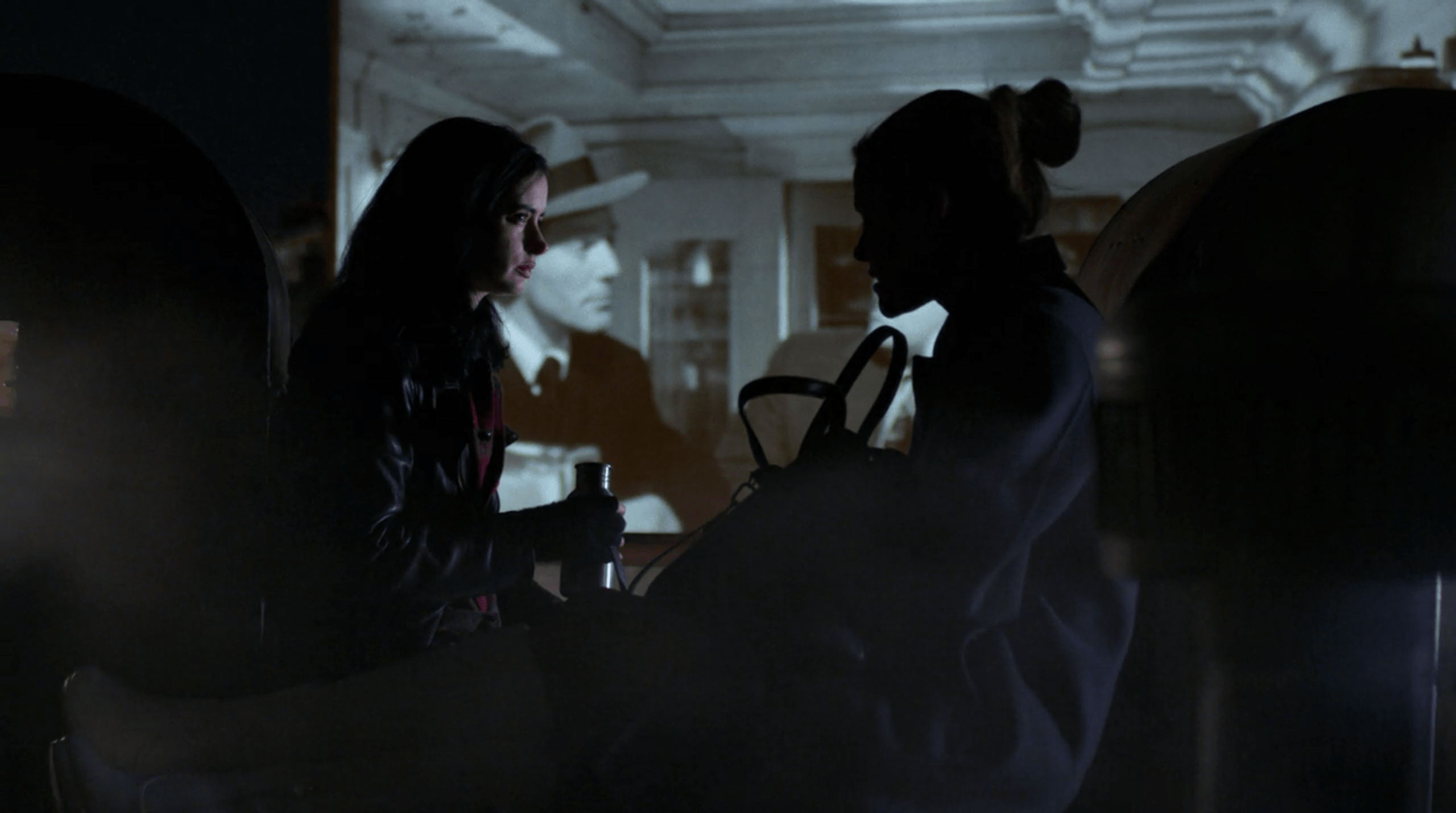

The closest thing to consensus surrounding the definition of film noir is that it is easier to identify than it is to define. [1] Even if you’ve never seen a film between 1941 and 1958 (inconclusive dates occasionally given to mark the noir era), the building blocks of the genre are easily identifiable; this includes the hard-boiled detective, the seductive but deadly femme fatale, low-key photography, and an often jazz inspired soundtrack. [2] We get all of these things in the Netflix show Jessica Jones – the noir classic The Killers (1946) even makes an appearance in the first episode of the second season. The show quite consciously attempts to blend two genres that are thought of as far from each other: film noir and the superhero narrative. [3] Not only does the show blend these genres, it experiments with traditional noir in ways that are rarely seen. Season one explores neo-noir with inverted gender roles: Jessica (Krystin Ritter) as the hard-boiled detective and the seductive but evil Kilgrave (David Tennant) as the femme fatale. This sort of inversion, while still rare, can be seen in films such as Bette Gordon’s Variety (1983) and Rian Johnson’s Brick (2005). I will be focusing here on the second season, which goes further into genre bending, exploring what a nearly all-female noir means. In addition, I will be exploring how this hybridity of genres allows for a traditionally more superficial genre (superhero narratives) to explore very real and difficult topics such as trauma, abuse, agency, and power.

The genre of noir, posthumously named by French cineastes, grew from wartime and post-war male anxieties about the changing landscape of gender-roles. [4] The femme fatale grew from this paranoia as well; a woman who is beautiful and yet also treacherous, “criminally depraved and castrating in their desires”. [5] Acting as her counterpart, the hard-boiled detective is synthesized in the stereotypical Humphrey Bogart persona: tough, introspective, emotionally repressed, and fond of whiskey. [6]

While Jones embodies the latter role (whiskey and all), Kilgrave’s death leaves the femme fatale role open at the beginning of the second season. With this male threat to her gone, Jessica is able to focus less on the trauma inflicted by Kilgrave, and more on the unresolved mystery surrounding the origins of her powers. The alluring but deadly role is filled by Jessica’s mother, Alisa (Janet McTeer), who until the sixth episode (and 17 years of Jessica’s life) is presumed dead. Alisa is, of course, drastically different from Kilgrave, and this unusual role pairing of mother and femme fatale accomplishes a number of objectives. First, it redefines what it means for a woman to be alluring yet treacherous, qualities that do not have to be intentionally malevolent. Alisa’s allure comes quite obviously from the fact that she is the mother Jessica believed she lost. Her posed threat is outside of her control, her rage a side effect of the genetic experiments performed that she wants to tamper but truly seems unable to. Second, putting Alisa in the role of femme fatale allows the superhero genre to explore the complications of parent-child relationships, particularly their potential for being destructive and damaging. Alisa is quite literally deadly, but she is a danger to more than Jessica’s physical well-being.

Throughout the series, Jessica struggles with her identity and the gap between the anonymity she desires, and the hero others want her to be due to her abilities. The second season finds Jessica hunting down the mysterious IGH, the group that conducted experiments on her and her mother after their deadly car crash. While her motivation is originally selfish, her search ramps up as others like her start to be murdered in quick succession, her motives becoming more and more based in a moral obligation to society. It is through this part of the season that we believe Jessica may be moving towards the role of hero, even if it is hero with a noir twist.

When Jessica discovers her mother, as well as the doctor who conducted the initial experiments, she immediately contacts the police, wanting to turn in the figures responsible for the recent stint of murders. However, as she waits for them, the pull of wanting to have a relationship with her mother becomes more and more powerful, leading them to escape and run before the police can arrive. Jessica recognizes that this is not necessarily the right move, even telling her mom that everything in her keeps telling Jessica to turn her mom in. This initial decision leads farther and farther down a moral rabbit hole—the more she gets to know her mom, the more Jessica can forgive in regard to her mom’s behavior. Any line she may have walked between hero and outlaw disappears when she chooses to flee the country with her mother. While Alisa’s aggression does not threaten Jessica directly, her violence towards others jeopardizes Jessica’s already waning moral code, and ultimately her ability to be a hero, not a “masked vigilante” as so many call her throughout the show’s first few episodes.

Kia Groom wrote of the show’s first season that while “it masquerades as a show about heroes and villains, ultimately Jessica Jones is not a fantasy. It’s the reality of existing in a patriarchal society that does everything it can to silence, dismiss, and ignore women”. [7] This season once again utilizes this masquerade, and Jessica’s decision is about the severe difficulty in navigating a toxic relationship with her mother: do you act in your best interest and cut them off, or do you maintain the relationship knowing it is damaging?

As Jessica develops a relationship with Alisa, her relationship with her sister, Trish (Rachael Taylor) begins to deteriorate. Within this relationship, the noir roles are actually different than that of Jessica and her mother. Jessica becomes the femme fatale to Trish’s hard-boiled detective. Throughout much of the first season, Trish acts as a foil to Jessica—not only is she opposite in appearance (blonde hair to Jessica’s black, designer clothes versus ripped jeans), but she has a family, a successful career in the public eye, and has overcome serious addiction issues. When Jessica chooses her mother despite what her conscious tells her, Trish picks up the investigation of IGH and those involved. Her sobriety lapses, her once clear moral code begins to waver, and she shuts herself off emotionally from those around her—checking off all of the qualifications for the noir detective role. Jessica’s allure to Trish is the same as her threat: her powers. Jessica tells Trish to stay out of the investigation, worried for her safety. Consistently, this drives Trish’s desire to keep pace with Jessica even more. Like Alisa, Jessica becomes unintentionally alluring and treacherous to Trish, further changing the concept of the femme fatale. Ultimately it is Trish who saves Jessica from her mother, removing the threat of the femme fatale in order to allow Jessica to return to society. However, as in traditional noir narratives, no one remains unscathed. Jessica’s punishment is the loss of her mother, while Trish lands herself in the hospital after voluntarily subjecting herself to the experimental genetic editing. As this is how the season ends, it will be interesting to see who encompasses what role as the show continues.

Historically, superhero narratives have focused primarily on more dichotomous issues of good versus evil. As the genre has grown, this has changed and superhero narratives deal with the complexities of topics such as racism, colonialism, and mental illness. Jessica Jones is not unique or alone in tackling these more serious issues. The show does, however, engage in genre-blending in a more ambitious way than Marvel has ever attempted before. Not only does this change the preconceived notion of a superhero narrative, but it also updates noir in an incredibly unique way. Returning to Groom’s quote, the show successfully utilizes the masquerade of superheroes and the conventions of noir to bring into conversation topics that are marginalized or difficult to discuss such as violence towards women, toxic relationships, and sexual trauma.

Image Credits:

1. Jessica Jones, Season 2, Episode 1 (Author’s screen grab)

2. Jessica and her presumed dead mother, Alisa.

3. Jessica is afraid for her sister’s safety, due to her lack of powers.

Please feel free to comment.

- James Naremore, More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 9. [↩]

- Naremore, More Than Night, 10. [↩]

- Brian Kenna, “Marvel’s Jessica Jones (review),” Science Fiction Film and Television 10, no. 2 (2017): 289-293. [↩]

- Jack Boozer, “The Lethal Femme Fatale in the Noir Tradition,” Journal of Film and Video 51, no. 3 (Fall/Winter 1999/2000): 20, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20688218. [↩]

- Boozer, “The Lethal Femme Fatale,” 22. [↩]

- Naremore, More Than Night, 21. [↩]

- Daniel Binns, “‘Even You Can Break’: Jessica Jones as Femme Fatale,” in Jessica Jones, Scarred Superhero: Essays on Gender, Trauma and Addiction in the Netflix Series, ed. Tim Rayborn, Abigail Keyes (North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2018), 14. [↩]

Pingback: The Conversation: Jessica Jones, a super-detective for the Marvel generation - RokzFast

Pingback: The Conversation: Jessica Jones, a super-detective for the Marvel generation - NZ Herald | Visual Assembler

Pingback: - My favourite detective: Jessica Jones, a super-detective for the Marvel generation