FLOW 2018: Roundtable Questions – Call for Responses

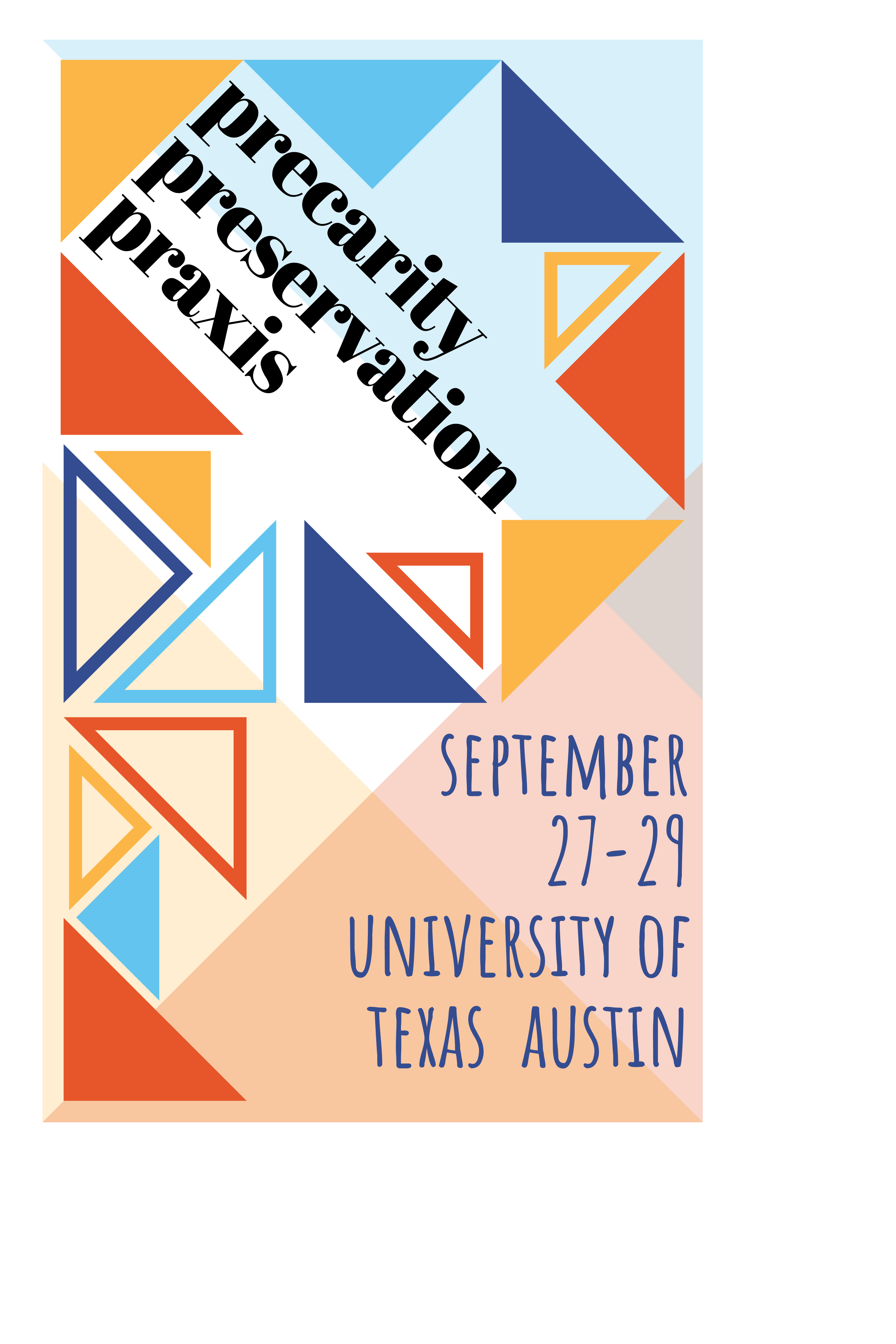

With the casualization of labor and the instability of the job market, precarity has become an increasingly pressing issue for both the media industries and the academy. Equally precarious is the state of preservation, as the production and circulation of media content outstrips the resources and workforce assigned to preserve it. Woven throughout and between precarity and preservation is praxis, the ways in which labor, strategy, and skill are marshaled to combat these threats in the industry and in academia.

Flow engages scholars in historical and contemporary trends and developments within media culture through a series of roundtables questions generated by the Flow community. Continuing this proud tradition, here are the 2018 conference roundtable questions exploring this year’s theme of precarity, preservation, and praxis.

- Rethinking Labor Histories and Production Cultures in #MeToo and #TimesUp Hollywood

- Syndication, Box Sets, & Streaming: Forming the Television Canon

- Here Today, Forgotten Tomorrow: Preserving Television & New Media

- Media Law and Policy in the Trump Era

- Precarious Pedagogies: Responding to Current Events in Media Studies Classrooms

- Aesthetics & Anxieties: Contemporary Dystopian Television

- Media(ted) Archives: The Politics of Saving & Making Media Histories

- Researching the Teleplay: Histories and Methods of TV Screenwriting Studies

- Considering Contemporary Television’s Ideological Power

- The Sports Television Personality

- The Interactive Documentary and its Uncertain Futures

- Paths to Professionalization: Streaming Video, Content Creators, and Influencers

- Preserving Pornographic Media

- The Past, Present, and Future of Television Commercials

- Theorizing TV Sound: Listening to Television Now and Later

- Television Literacy in the Classroom and Beyond

- YouTube’s Kids: The Future of Television and Consumption

- Flowing Forms: Changing Media, Changing Bodies

- Transnationalization of Quality Programming

- Remakes and Reboots: The Value of Mining Television’s Past

- Media Discourses: The Cultural Forum of School Shootings

- Hierarchies of Labor and Authorship in The Television Ecology

- The Political Economy of Participatory Cultures and Their Platforms

- Instability/Stability: Catalogue Titles, Streaming Services, and Physical Media

- Best Practices for Digital Research

- Latinx Representation in Hollywood

- The Growing Intersection of the Indie Film Business, Streaming, and Television

- Anti-Neutral Internet: Internet-Distributed Television after Net Neutrality

- Queer Forms, Global Contexts

- Assuming Risk/Lacking Support: Navigating the Research Process

- Preservation Terminology and Archival Discourses

- Vevo as Music Video’s Digital Archive

- Save Points: Video Games and the Preservation of Play

- In Data We Trust: The Limits of Algorithmic Culture

- Podcasts: Radio Revisited or Audio Reimagined?

- Platforms & Technology

- The Precarity, Preservation, and Praxis of Sports Media Labor

- It All Becomes Screen History?: Teaching Media Histories

- But What About Flow?: Programming Structures in the Post-Network Era

- What Would A Television Preservation Task Force Look Like?

- Changing Channels

We invite responses in the form of 150-word abstracts. To ensure full consideration, please submit your proposal using this form by Sunday, May 20 at 5 PM (CST).

The committee kindly requests participants respond to one topic only. However, we encourage you to let us know if you are willing to participate in another roundtable in case we receive too many responses for your first choice. We will notify all participants via e-mail in mid-June. Upon acceptance, respondents will be asked to expand their abstract to a 600-800 word position paper, due in late August 2018.

- Rethinking Labor Histories and Production Cultures in #MeToo and #TimesUp Hollywood

- Syndication, Box Sets, & Streaming: Forming the Television Canon

- Here Today, Forgotten Tomorrow: Preserving Television & New Media

- Media Law and Policy in the Trump Era

Since the new administration took over in January 2017, there have been many significant changes and challenges to U.S. media law and policy. This roundtable will focus on the important questions of how media law and policy in the Trump era could affect the future of the media and culture in the U.S. and around the world. Some topics may include: What do the responses from the DOJ, FCC, and Trump to the proposed mergers and acquisitions of AT&T/Time Warner and Disney/Fox tell us about the current state of antitrust law and media consolidation? How should content on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter be regulated to avoid “fake news” and interference from foreign agents like Russia? What does the FCC’s revision of ownership cap rules mean for the future of local broadcast media? How does the new tax law and proposed deregulation of the financial industry affect Hollywood studios, independent productions, and the financing of media projects? Will the recent attempt by lawmakers in the wake of another horrific school shooting to shift the blame for such tragedies to violence in movies and video games result in any changes to content regulation? How could the #metoo and #timesup movements alter everything from employment contracts to diversity and inclusion in Hollywood? [page up]

- Precarious Pedagogies: Responding to Current Events in Media Studies Classrooms

While university classrooms have a history of engaging with difficult and timely topics, current political and institutional climates have seen increased scrutiny of instructors for what they teach and how they teach it, often with very real consequences. With events at the national level (2016 election, police violence, #MeToo campaign) and on campuses (Richard Spencer, racist flyers), faculty and students must navigate situations that are complex, personal, and fraught. Some disciplines may seem insulated from these topics but the humanities in general, and media studies in particular, directly engage with these issues as part of our course content.Although research suggests students appreciate when faculty address traumatic events (Huston and DiPietro; Kardia et al), many instructors are hesitant to do so for a variety of reasons (identities, confidence, job security, campus climate). Since the last Flow conference, however, a reality TV personality has become president, any media content can be labelled “fake news,” and the Weinstein scandal emerged in a global media capital. All this in addition to the central role that identity, representation, and power play in media studies syllabi.

Therefore, what considerations should be made in addressing specific incidents? How can media texts be leveraged to unpack these topics? What strategies or best practices can be brought to bear in these situations? What is the role and function of tenure within institutions to protect those in more precarious positions (graduate students and adjunct instructors)? How does this pedagogy play out differently across diverse student populations and institutional settings? [page up]

- Precarious Pedagogies: Responding to Current Events in Media Studies Classrooms

- Aesthetics & Anxieties: Contemporary Dystopian Television

It can be argued that during specific historical moments, American television has reflected an overwhelming sense of precarity, anxiety, and fear that was also pulsing through American society. Much has been made of programs like The Handmaid’s Tale (2017-present) being one of the first examples of Trump era art. The truth is The Handmaid’s Tale was in production before Trump won the election and it follows a pattern of dystopian TV that dates back to shows like The Walking Dead (2010-present), Fringe (2008-2013), Jericho (2006-2008), Mr. Robot (2015-), and Into the Badlands (2015-), among others. In what ways does this pattern of post-apocalyptic TV, which is arguably a post-911 phenomenon, provide a pattern of cultural clues to our current societal moment? These programs (and others) reflect specific anxieties about the world and about the United States, but how founded are the fears? Should we collectively be more or less afraid of the established structures that have girded whatever America it is that we have imagined? And if society collapses, should we fear what may grow out of the ash heap? [page up]

- Media(ted) Archives: The Politics of Saving & Making Media Histories

Few people would reject the premise that digitally archiving the mass media—film, television, radio, video games, and the like—is important cultural and scholarly work. Though it it can require tremendous human and computational effort, such labor facilitates the study of fragile, rare, or inaccessible materials, as well as enables the “distant reading” (i.e., data mining) of these materials en masse. The democratization of media past, present, and future—thanks especially to digital archives—would thus seem to be an unassailable pursuit, no matter if done in special collections, an academic unit, a community center, a not-for-profit organization, or even a transnational conglomerate. But it is not—a legion of obstacles stand in the way of making media archives fully fulgent. From the legal mechanisms of intellectual property protection, to the limited resources available to archivists to do their work, to the nomenclatural policing of designations such as “archive” and “archivist,” to the paucity of international standards by which materials might be expeditiously processed and located, the politics and practices of media archive creation, management, and sustainability are often confusing, discouraging, and infuriating. What is it about the mass media that complicates arguments promoting their historical value? What ideological motives might connect the policing of archive development with other questions circulating in media studies such as those concerned with monoculturalism, casuistry, and the dangers of presentism? Finally, how can we as a practical and pedagogical matter support existing and emerging archives that will aid future generations in the making of media histories? [page up]

- Researching the Teleplay: Histories and Methods of TV Screenwriting Studies

Why do writers write what they write and how do we investigate this question? As television scholars increasingly turn their attention towards researching the teleplay as a creative work in its own right (McDonalad, 2013; Millard, 2014; Novrup 2013), what approaches and methodologies might be adopted in order to understand the teleplay as a series of creative decisions? To what extent are television writers impacted by industrial concerns such as genre, timeslot and network? How are they influenced by other television texts as well as other non-televisual sources such as games, films and music? What gets lost in the re-writing process and what is gained? And perhaps more pertinently, how do television researchers begin to unearth and quantify the answers to these questions? [page up]

- Considering Contemporary Television’s Ideological Power

As we consider the changing landscape of television and new media, TV Studies itself seems precarious. The constant stream of technological development, increasing fragmentation of audiences, and expansion of programming and distribution outlets has called into question the utility of foundational TV Studies concepts like networks, flow, and especially the cultural forum (Newcomb and Hirsch 1983). The sheer quantity of TV production and the variety of ways to consume TV can make it feel impossible to find shared reference points. Older formulations of television as a cultural forum, a place where large national audiences share cultural experiences and hash out complex or taboo ideological changes or differences, have thus fallen out of favor. If television’s representational power is no longer consolidated in or monopolized by a narrow range of dominant institutional voices, television arguably seems more diverse and its power more diffuse and dispersed. Yet, in the contemporary political climate, in which consciously sowing openly affective and ideological division is an effective path to power, it seems that denying the continued cultural power of television is an effective way to dismiss a powerful mass cultural forum still in operation. As Stuart Hall taught us, television representation has real power to create cultural reality, not simply to reflect it. This question asks us to consider, then, how TV scholars can grapple with these new technologies, expanding content offerings, and fragmented audience configurations while still acknowledging a broad or comprehensive sense of the ideological power and influence of TV on audiences? [page up]

- The Sports Television Personality

As the study of celebrity has increased in recent years, sport studies has seen a corresponding rise in scholarship focusing on sport stardom. With few exceptions, though, this emerging line of sport scholarship has focused on star athletes who have found their way to prominence by way of their athletic triumphs. Excluded from the academic discourse, then, have been the many celebrities who have obtained their fame either partially or fully by way of the many other component parts of the sports media landscape that extend beyond the playing surface. Dominating this group has been the sports television personality – a diverse category that includes figures ranging from studio hosts like Jemele Hill, Rachel Nichols, and Katie Nolan to announcers like Joe Buck and Jim Nantz to reporters like Erin Andrews, Jeremy Schaap, and Adrian Wojnarowski. How might we understand these liminal figures who emerge in media environments that surround athletic competition? How might we use their celebrity to interrogate the complex relationship between sport and media? How, too, can we understand these figures in the context of television fame and the presentation of the self? Furthermore, given the recent cries for many of these personalities to “stick to sports,” how can we make sense of sports television personalities’ role within culture and society, including their ability – or lack thereof – to engage with policy and politics? How, for example, might we understand how their political engagement is shaped by a precarious positioning between employers, fans, rights partners, and sponsors? [page up]

- The Interactive Documentary and its Uncertain Futures

The nascent field of iDocs, or interactive documentaries, has witnessed some growth in recent years. The National Film Board of Canada distributes and promotes materials on their website and has emerged as a center for creative producers who work across media and operationalize the affordances of digital media and the robust media environment of the web browser. Projects like Immerse — a partnership between MIT OpenDoc Lab, Sundance Institute, IDFA DocLab, POV, Tribeca Film Institute, and Points North Institute — have begun to publicize and discuss the potentials and the pitfalls of the emerging media with regularity. The New York Times has partnered with Google to distribute its Cardboard VR device to feature its interactive and immersive media content. While VR is having its creative awakening, the field of documentary filmmaking seems to plant its flag with well-funded media properties, while the technology itself becomes more robust and perhaps prohibitive to the average storyteller. To turn a phrase, interactive documentary hasn’t found its flow. From a storytelling perspective, what are the promises of this emerging art form? What are its drawbacks and limitations? And what would make interactivity more accessible to fledgling storytellers and documentary filmmakers? [page up]

- Paths to Professionalization: Streaming Video, Content Creators, and Influencers

For a generation of media consumers, streaming media platforms like YouTube and Twitch are simply part of the media landscape: their creators are celebrities, and their content is comparable to—if distinguishable from—television shows or movies. However, unlike traditional media, these platforms provide the (seemingly) easy opportunity for those consumers to become producers. The next generation of YouTubers and Twitch Streamers grew up in a time when these were career paths, not hobbies, the terms of professionalization negotiated through the intertwined forces of platform affordances, community standards, and industrial regulation (or lack thereof).This roundtable will consider how the path to professionalization is being negotiated by this next generation of “content creators,” and how YouTube, Twitch, and other platforms are adapting to the evolution—or, one might argue, devolution—of their userbases. How are affordances of sponsorship—through streaming donations, merchandising, or Patreon—reshaping how creators monetize their content? How have YouTube’s attempts to use monetization as a form of punishment for content creators who run afoul of community standards—e.g. Logan Paul—impacted their relationship with their userbase? What is the role of legacy media in an era where the role of multi-channel networks in YouTube’s future seems less certain than when Disney invested in Maker Studios in 2014?

By identifying points of tension within these communities, this roundtable seeks to better understand the foundations on which the future of content creation is being built, and the precarity the creators and the platform owners face in the process. [page up]

- Media(ted) Archives: The Politics of Saving & Making Media Histories

- Preserving Pornographic Media

Much has been said of the need for archival preservation of pornographic media texts which, because of their specific cultural function and means of circulation, tend toward ephemerality. However, as Frances Ferguson and David Squires have argued, the very process of archivization, in its sequestration of sexual materials from the world of erotic life, may render these materials un-pornographic. Yet, as scholars such as David Church and Whitney Strub have argued, the archive itself is not an erotically neutral space, as both historiography and preservation efforts are motivated by a passionate attachment to and investment in pornography’s ephemerality. These issues are compounded when one considers pornography’s move online and the proliferation of new media technologies, which, as Tim Dean notes, seem to produce “more porn archives than we know what to do with.” How ought the field balance the ongoing need for pornographic film and video preservation while also attending to the shifting media landscape and to the need for new tools to study it? What strategies are needed to archive, organize, and preserve new media pornography? Are there specific kinds of pornographic media texts (for example, public access cable shows) that are currently being overlooked by archival efforts? What theoretical frameworks are needed to facilitate work on pornography that is missing from the archive and is potentially lost? Is there a way to either avoid or account for the effects that institutional legitimation has on erotic texts? Would this require new archival practices? [page up]

- The Past, Present, and Future of Television Commercials

Despite the decline of linear television, advertisers are still intent on reaching audiences through television and are experimenting with strategies, including sponsorship, brand integrations, product placements, and cast commercials, designed to reduce audience alienation. What could we glean about future television advertising strategies from past and present practices?- How are advertisers’ current strategies for reaching audiences through branded content similar to or different from historic strategies?

- As television advertising changes, how are production companies and ad agencies retooling themselves as producers of new forms of commercials?

- What are some of the changing dynamics, shifting leverage points, and emerging financial incentives among linear networks and advertisers as they negotiate how to deliver commercials to increasingly resistant audiences?

- If major advertisers withdraw from network television, as they once withdrew from network radio, which media platforms and content genres may benefit the most?

- Is the 30-second commercial a dying format?

- In what ways is YouTube shaping the new nonlinear television industry to serve advertisers? Are YouTube “pre-roll” commercials different from conventional commercials or not? Are new commercial aesthetics emerging on YouTube? [page up]

- The Past, Present, and Future of Television Commercials

- Theorizing TV Sound: Listening to Television Now and Later

Largely ignored in the kerfuffle over whether Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) is best labeled television, film, or the catch-all term “streaming content,” were the sounds of the text. Praised throughout his career for his attention to music, sound effects, and the myriad sonic textures created by performers’ bodies, David Lynch’s sound creation and control for the series was as innovative as ever. But are these the sounds of television or film? What is streaming content sound, anyway? Arguably, the sounds of television, like the images of television, begin as performances. Could the “liveness” of television be theorized alongside the history of popular music and the audio technologies created to turn ephemeral music into durable commodity? Television sound itself has always been a combination of performed sound and recorded sound (from sound effects to music); TV sound is heterogeneous before audiences can make use of it as a performance or convert it into a recording. This roundtable invites discussion of TV and new media sound, the technologies of preservation and the technologies of audio (re)play. To what extent do TV and new media share characteristics with popular music and film sound? How do we listen to television and new media? In what ways can we theorize the sounds and technologies of TV sound? What is the history of listening to television and new media in the absence of a screen? How can we further historicize TV sound and the technologies of TV sound? [page up]

- Television Literacy in the Classroom and Beyond

In liberal circles, we often hear commentators bemoaning Trump’s claims of fake news and citing “media literacy” as the self-evident solution. But what does “literacy” entail? How does one teach it, in practical terms? This panel seeks to explore the distinctive characteristics and formats of TV-based news sources (broadly defined) and invites a broad range of expertise in TV studies. The panel’s central focus is less news than it is our field’s understanding of the ways television, as a distinct visual medium, communicates through form, genre, character, and institutions as crucial to teaching television literacy. The panel therefore will seek to formulate the multiple strategies TV and new media scholarship offer to develop a literacy curriculum, applicable within our classrooms but also through public intellectual work as well.Among the questions this panel may pursue:

- How do the business models of television news influence the production and marketing of content?

- Is objectivity possible, or even desirable, in a media format built upon visual communication, editing techniques, and other production techniques?

- How do frameworks of celebrity shape the production and reception of TV journalists and commentators?

- How might theories of race, gender, orientation, and class provide new forms of critique to evaluate the credibility of television news programming?

- How do we de-mystify the various ideological meanings of the aesthetics undergirding the production of television news?

- What are the goals of viewers of television news? What benefits or limits accrue around terms such as accuracy, credibility, entertainment, truth, and facts? [page up]

- Television Literacy in the Classroom and Beyond

- YouTube’s Kids: The Future of Television and Consumption

The profitability of content created for and by children on social media platforms such as YouTube has sparked an entire sector of content catering to young children. The panel looks at the cultivation of child “influencers” as a part of the emergent digital media landscape and children’s media industries, including the emergence of entire genres such as “unboxing.” In addition to social media channels and platforms like “YouTube Kids,” digital streaming companies like Netflix and Amazon have invested heavily in producing targeted content. Corporations have always viewed children as a target demographic, but with the success of child-created content large companies are also investing heavily in marketing and content through mobile phones and connected viewing practices. This panel aims to provide a broad overview and mapping of the current landscape of children’s entertainment and media, including the rise of very young children as an expressed target demographic, in an attempt to articulate the future of media authorship, labor, and consumption. Attention is paid to the political economy implications of a children’s media industry as well as the critical and social influences on conceptions of aspirational purchasing and marketing melding with the affordances of digital technology and platform design. Child-created content is also the site for discursively codifying particular articulations of concepts such as family or gender to reinforce purchasing and marketing norms within these sites. [page up]

- Flowing Forms: Changing Media, Changing Bodies

Media presuppose bodies. In their role as moderators, media act “in-between” for bodies: translating signals, distributing content, connecting people. Media are thus responsive to bodies, and likewise bodies are responsive to media, with both transforming through their interactions, bridging the physiological, the technical, and the cultural. Bodies are therefore more than just receptors for media content but constitutive to media forms and necessary for media praxis, arguably performing like another platform for media convergence. However, bodies remain undertheorized in media studies outside of representation.As such, this query seeks responses to illuminate how media and bodies affect each other, especially through moments of significant cultural, industrial, and technological change. Specifically, how do changes in media and bodies correspond? How do they shape each other? How do these connections and their attendant transformations relate to hegemonic systems, whether legitimating operations in media or identity hierarchies in bodies? What exchanges between bodies and media are critical to consider in contemporary culture, and what must be further examined from the past? Why do these interactions matter, and how might they affect experiences of both media and embodiment in the future? [page up]

- Flowing Forms: Changing Media, Changing Bodies

- Transnationalization of Quality Programming

The much disputed definition of quality programming is further complicated by the increase in transnational flows of formats and programs during the last decade. Streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu and Amazon have become new venues of access to foreign content alongside the existing cable channels in the United States. The international popularity of shows like Forbrydelsen, Borgen, Bron/Broen, Luther, Les Revenants and Broadchurch also paved the way for a new wave of American remakes. Mostly oscillating between streaming platforms and cable channels, which are associated with quality programming, these programs and their format adaptations raise important questions about what “quality programming” means. This roundtable seeks to understand how the current context of transnational television flows influences the definition of quality programming in light of the following questions: Is it possible to talk about an on-going transnationalization of that definition? What is the role of digital technologies in this transformation? What does the co-existence of originals and their remake reveal in terms of hierarchical implications present in the notion of quality programming? [page up]

- Remakes and Reboots: The Value of Mining Television’s Past

The surge of remakes and reboots is perhaps one of the most apparent trends on television today. The industry is mining shows across genres from the 1960s (Hawaii Five-0; The Twilight Zone); 1970s (One Day at a Time; S.W.A.T.); 1980s (Dallas, Roseanne); 1990s (The X-Files, Twin Peaks); and 2000s (Roswell; American Idol) to serve as catalysts for new content. The simple explanation for revisiting older content is that it’s less risky to rely on existing and presold intellectual property. Furthermore, these shows have the potential to draw in both older audiences of the original shows inspired by nostalgia and younger audiences who see the shows as original. While the industrial reasoning behind this trend may appear commonsensical, the implications of these many remakes and reboots is perhaps a bit more layered. This roundtable will address both the industrial and cultural implications that emerge from the proliferation of remakes/reboots. Potential questions include: How are remakes/ reboots a reaction to the changing television ecosystem? What are the industrial ramifications of the growing reliance on nostalgia for television content? How is the value of the older, “original” texts affected by remakes and reboots? Why are younger audiences drawn to revisit original versions of some shows and not others? Do remakes and reboots successfully encourage co-viewing by multigenerational audience members? By exploring these questions surrounding remakes and reboots, we can move beyond a basic understanding of their industrial function to consider their more nuanced role in shaping both the television industry and television culture. [page up]

- Media Discourses: The Cultural Forum of School Shootings

Following the tragic shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School this year, Donald Trump claimed that violent video games, movies, and the perpetrator’s mental health were to blame for the massacre. Even though scholars and researchers have debunked the hypodermic model of media effects that sutures violent entertainment and violent youth (see Jenkins), the perpetuation of these causal connections stalls any progress to prevent future school shootings. Trump’s statement about gun violence mimicked those surrounding the causes behind the 1999 massacre at Columbine High School, precariously leaving the public debate in the same place that it was nearly two decades ago.This roundtable endeavors to discuss the media’s role in framing the narratives behind the causes of school shootings, and how those narratives may affect public debates and political legislation about this issue (see Birkland and Lawrence). In their theorization of television as a “cultural forum,” Horace Newcomb and Paul Hirsch suggest that television programs can highlight and comment on ideological issues. How does the media frame the issues surrounding mass shootings? Is there a distinction between the topics that fictional representations and news coverage of mass shootings represent? For instance, do fictional representations concentrate on mental health issues rather than explicitly arguing for gun control legislation? How has the cultural forum changed with new media technology? The breadth of the internet has led to the dissemination of far-right conspiracy theories surrounding “crisis actors” to mainstream media outlets. For instance, a conspiracy theory video concerning David Hogg – a survivor of the Parkland shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School – was the top trending YouTube video on February 21, 2018 before its removal and Hogg denied these false accusations during a CNN interview. How has user-driven content like these videos shaped (or been shaped by) the current public sphere surrounding school shootings? Finally, how has the increase of niche partisan television networks and online communities affected the cultural forum? Is media increasingly becoming an “echo chamber” (see DiFonzo), thereby preventing any meaningful progress in this debate? [page up]

- Remakes and Reboots: The Value of Mining Television’s Past

- Hierarchies of Labor and Authorship in The Television Ecology

Media authorship scholarship often focuses on above the line investigations via individual studios, brand identities, directors, showrunners, screenwriters and stars; or, in contrast, via case studies of below the line workers’ labor and their positioning in a media hierarchy. Although the binary is critical for the ways it illustrates the various power structures at play, it does not inherently exclude the presence of an interconnected media ecology that recognizes the collaboration, influence, and convergence between below-the-line and above-the-line media workers. Just as fan studies scholars reveal that participatory culture shapes media cultures, a production-based media ecology prevails in conceptually-driven television projects that serve under the delegation of a showrunner (under the restrictions of studio/network rule above them) who balances creative and managerial duties. From foley artist to costumer, sound and set designer, each job is tasked with maintaining the consistent vision and brand identity of a showrunner, while also attempting to assert their own authorial identity that distinguishes their work. In fact, many of these seemingly invisible labor practices are what contribute to the tangible world building of a series and discourses of quality TV, and the digital era allows for their self-branding to reveal the work that goes on behind their collaboration with above the line creative decision-making and subsequent delegated individual contributions.How can historical and contemporary based TV and media industries scholars utilize integrated hybrid cultural and production studies methods? And how can these methods reveal the on- and off-screen dynamics of representation, authorship and agency for precarious below-the-line laborers who work under the delegation of showrunners in an intrinsically collaborative and interconnected media ecology? [page up]

- The Political Economy of Participatory Cultures and Their Platforms

At the beginning of December in 2017, Patreon sent out emails to site users announcing a change in how the company would process payments and charge fees to those using the site to support creators with monthly payments. After a week of controversy and protest, the platform announced “We messed up. We’re sorry, and we’re not rolling out the fees change.” Among other missteps, Patreon apologized for not involving the platform’s users, both the creators who receive payments and patrons who make them, earlier and more substantively in their decision-making process. The Patreon example is only the most recent of many controversies over the governance of digital labor platforms in recent years. While control over workplace policies and struggles over compensation are evergreen issues in the history of industry and labor, the ever-increasing prominence of digital platforms adds both new wrinkles and new tools for change.This roundtable dives into the political economy and participatory cultures of digital labor platforms. What ethical responsibilities do privately held platform companies have to those who depend on their sites for work? Many of these platforms are founded with utopian goals and visions of a better future—how can these be sustained as they grow in scale? Do workers have responsibilities towards platforms? How can the history of unions and collective bargaining inform struggles for better compensation and healthcare in the growing casual economy, particularly when workforces like MTurk’s stretch across national borders? [page up]

- Instability/Stability: Catalogue Titles, Streaming Services, and Physical Media

A 2017 article in Paste makes the case that physical audio-visual media is more important than ever in the “ephemeral world of streaming.” The argument is that as streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Prime increase original productions and emphasize exclusive rights to high-profile properties over a deep catalogue, there has been a resurgent interest in physical media. This is especially true in the U.S. and the U.K., where small specialty labels have targeted niche audiences by releasing limited and special editions of hard-to-find films and TV shows that the major studios see no financial advantage in making available to relatively small audiences and are willing to license out for cheap.In addition to raising significant questions about the home video market as we move further away from the heyday of VHS and DVD sales, the instability of streaming services’ catalogues prompts us to consider its impact on archival practices and, in turn, viewership practices in significant ways. What metrics are used to determine whether or not a film, TV show, or album is “worth” releasing by a major studio? What care is put into restoration or preservation efforts as a consequence? What are the potential consequences – good or bad – of leaving such work to third-party companies and public archives? What properties are audiences aware of in this environment and how does that impact assumptions about canonical importance? This panel invites discussion of these issues and more, including their relation to other media industries, including record and video game companies. [page up]

- Best Practices for Digital Research

While critical cultural studies scholars can innovate how they conduct research through new media technologies, these tools often recreate the problems of established methods or create new problems all together. Keyword searches are often undermined by dirty OCR, while attention to materiality is lost when we access digital versions of sources. Watching a DVD of a 1960s television show means we lose the context offered by its place in the television schedule or the bumpers and commercials integrated within its original broadcast. Social media provide access to a range of audiences and fandoms, but do little to lessen the ethical concerns of observing and interacting with a community.This panel asks scholars to consider the ongoing ethical, practical, and methodological concerns associated with using digital tools and methods, especially in light of recent news regarding Facebook’s corporate practices. What precautions and practices should guide us in conducting digital ethnographies? What challenges emerge from using digital archives over traditional archives? Following recent work by scholars like Safiya Umoja Noble, how do search algorithms reinforce and perpetuate social inequalities? How useful are digital methods introduced by scholars like Richard Rogers for critical cultural studies research in television and new media? How do we research online identities, communities, and behavior while respecting individual rights, especially when platforms we may be using so rarely do? In this panel, we welcome a broader discussion of how new media technologies improve or undermine best research practices in critical cultural studies of television and new media—or, perhaps, simply continue those ongoing issues we have as researchers. [page up]

- Latinx Representation in Hollywood

The 2017 Emmys were lauded as the most diverse ever, with key wins for Black actors Donald Glover and Sterling K. Brown, Black screenwriter Lena Waithe, South Asian American actor and screenwriter Aziz Ansari, and British Pakistani actor Riz Ahmed. This vision of diversity again left out Latinxs, however, with only a nomination in the guest actor category for Nuyorican playwright and actor Lin-Manuel Miranda and a win for half Argentinian-American Alexis Bledel, also in a guest actor category. Part of the problem is Latinxs are still relegated to bit parts on television, with few opportunities to land lead roles. Save for the critically lauded Jane the Virgin (2014-present), Netflix hits Narcos (2015-present) and One Day at a Time (2016-present), and a small handful of other shows on cable networks, Latinx protagonists and storylines continue to be rare. This is despite the fact that there are over 55 million Latinos in the U.S. with a purchasing power of $1.5 trillion, according to the National Hispanic Media Coalition. Moreover, the problem is not limited to television. After not one Latinx actor was nominated in an acting category for the fifth straight year at the 2018 Oscars, the NHMC and its allies promised to protest the six major studios for their marginalization of Latinxs in the industry and in film narratives.This panel will seek to discuss the current status of Latinxs in Hollywood. While some interesting strides have been made in the last year, such as Latinos Édgar Ramírez and Ricky Martin co-starring as Italian fashion designer Gianni Versace and his Italian partner Antonio D’Amico in Ryan Murphy’s American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace (2018), and continued success for established stars like Gina Rodriguez, Pedro Pascal, and Oscar Isaac on the big screen, there seems to be an enduring resistance to green-lighting series and films revolving around Latinx characters or communities. In other words, “Peak-TV” is not making room for Latinxs, and increased diversity at awards shows post-#OscarsSoWhite has not impacted Latinx representation. Why does visible progress for Latinxs in TV and film continue to lag behind that of other minority groups on both the industry level and on camera? How can Hollywood push past seeing diversity as a White/Black binary? [page up]

- The Growing Intersection of the Indie Film Business, Streaming, and Television

In the past few years, streaming services have increasingly become involved in the acquisition and distribution of independently financed and produced films. One Vulture headline, for example, proclaimed Sundance 2017 as the “Year Netflix Tried to Swallow Sundance.” The recent presence of Netflix, Amazon, and other streaming services at festivals has become so prominent that the major companies’ lack of acquisitions at Sundance 2018 resulted in a whole other set of headlines that seemed to equate the streaming services growing disinterest with a lack of quality festival programming.At the same time that independent producers have looked to streaming services for financing and distribution, the indie business more generally increasingly has turned its attention to television. Cable networks and streaming services are hiring former indie filmmakers to helm their TV series, indie distributors such as Annapurna and A24 are moving into TV production and distribution, talent agencies are financing and packaging TV seasons as they previously packaged films, and festivals like Sundance, Toronto, and SXSW are featuring “episodic” tracks on their schedules.

This panel seeks to explore the growing intersections between the indie film business, streaming services, and the television industry. Response papers might consider questions such as: What new issues are arising as a result of this evolving indie film business/streaming services/television industry relationship? What are the implications of this cross-fertilization of indie talent (directors, screenwriters, producers, actors etc.) with television? In what ways has the attribution of indie with “quality” or “niche” evolved as a result of this convergence? What are the implications for film festivals as sites of exhibition, distribution, and deal-making? How might these new relationships continue to blur the lines between film, television, and technology companies? [page up]

- Anti-Neutral Internet: Internet-Distributed Television after Net Neutrality

As of December 2017, net neutrality no longer rules the Internet. By doing away with those protections, the FCC signaled their approval for the further concentration of Internet Service Providers, and media industries more broadly. This shift helps align Internet distribution practices with that of mega-conglomerate broadcast and cable distributors, who are also undergoing deregulation. Within the last year, the FCC also eliminated provisions restricting cross-ownership between newspaper, broadcast, and radio companies, and broadcasters are no longer required to have local studios. While the Internet was never regulated as a common carrier, doing away with net neutrality officially situated ISPs outside the realm of common carriage policy. Combined with the deregulation of cable providers and broadcasters, the future of television as an industry is up for debate again.In the post-network era, internet distributed television will be amongst the most radically affected by the FCC’s deregulation. Cable and Internet access have typically been bundled under the major service providers, but that relationship and the “bundle” model will certainly shift further without net neutrality protections for equitable access to and distribution of Internet content. Will we see the Internet more closely resemble cable packages, in terms of channels provided through a singular source? Or, as Internet distributed television continues to grow without net neutrality, will access to non-premium content be similarly cordoned off behind pay walls? For legacy content creators and distributors building in-house OTT services (like CBS All Access or Spectrum’s recently announced online only Stream service), how will a privatized Internet alter access to television content and change reception patterns? Will the rampant deregulation irreparably alter media industry practices in spite of the public interest? How will massive conglomerates utilize the FCC’s deregulatory stance to further concentrate their ownership holdings, and what implications will these changes have on television consumers? [page up]

- Queer Forms, Global Contexts

The amount and quality of LGBTQIA+ representation in media has advanced rapidly in the past two decades. On American television, and especially its online platforms, there is not only more gender and sexual diversity, but also a more intersectional depiction of racial and class-based diversity within the queer community, among other identity markers. At the same time, queer representations in other national and regional contexts are also being contested and transformed through the globalization and digitization of television and new media. The emergence of an androgynous contestant Li Yuchun on Super Girl (2005) in China, the popularity of the UK’s non-binary dating reality show Love Island, the “Flozimin” ship on Argentinian telenovela Las Estrellas, and the critically acclaimed comedy Please Like Me in Australia are some important examples of queer representations on television across the globe. Yet this global diversity of queer experiences is hardly visible in US television. With only a few exceptions—such as Adena on The Bold Type—American shows only represent the domestic queer experience. How much, and in what ways, do American shows cling to a locally-defined notion of queerness, and why? What roles do various media formats and delivery platforms play in maintaining or breaking that limitation? How does American televisual queerness fit within the global landscape of queer television, and how can these different perspectives be put into conversation? Furthermore, we welcome responses related to queer representation in television outside the United States. How is the queer experience presented in other televisual contexts, and what is its significance? [page up]

- Assuming Risk/Lacking Support: Navigating the Research Process

When media scholars apply to the Internal Review Board, the goal of the process is to protect the human subjects of their intended research. This is an apt and necessary step. But what structures are in place to protect the researchers themselves? Many researchers face threats to their physical wellbeing due to their work: they may be arrested, contract illness, or risk other forms of harm. But there are less dramatic ways in which researchers are threatened, as well. Other legal ramifications can extend from work involving extralegal networks of exchange, restrictions around the usage of given materials, or government censorship. And now more than ever, scholars are without guaranteed employment: we are independent scholars, underfunded graduate students, adjunct professors, and so on. These scholars are faced with precarious resources, whether it be to research databases, health insurance, or a living wage.This panel invites respondents to consider the different ways in which media scholars face precarity in their research. Where and when do scholars accept such risks, and what prompts or necessitates them to do so? When should researchers be able to expect support from their institutions when threatened by the circumstances of their work? Where do institutions intentionally withhold their support, why, and with what consequences? And finally, where can researchers without solid institutional backing turn for support? [page up]

- Assuming Risk/Lacking Support: Navigating the Research Process

- Preservation Terminology and Archival Discourses

Scholars not only conduct research in media archives, but such archives have also become the subject of research themselves. But how often do they enact and maintain archival principles? For example, many of these organizations rely on terminology and practices specific to archival science. We might ask how do the specific terms we use to describe the groupings of media texts and contexts we wish to preserve determine, intentionally or not, the practices we employ in our efforts to facilitate both preservation and access? What do the traditional archival tenets of respect des fonds, provenance, and original order mean in the context of television and new media libraries, collections, and archives? Indeed, how do we determine the difference between a media collection, a media library, and a media archive? Is this simply a question of semantics? How could a more intentional distinction between the theoretical frameworks, methodologies, and practices of library science, information science, and archival science inform our praxis and scholarship? [page up]

- Vevo as Music Video’s Digital Archive

As of March 2018, 94 of the top 100 most viewed videos on YouTube were music videos, all of which have over 1 billion views. Most of these videos are distributed by Vevo, a multinational joint venture between the “Big Three” record labels (Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment), which collectively controls over two-thirds of the global market share, indicating their sheer dominance in the industry. With Vevo (through YouTube’s platform) as the primary vehicle for music video distribution, we must consider the implications of this power being held by an oligopolistic cohort in the global music industry. Additionally, as YouTube hosts the majority of music videos, both past and present, we must consider Vevo as a digital archive and potential site of music video preservation.How is the global music industry being shaped and transformed by the business practices of Vevo and YouTube? How are production practices adjusting to the overwhelming global nature of YouTube’s viewership? In light of Vevo following in the footsteps of companies such as Hulu and Spotify, are artists and music video producers being compensated fairly? Is Vevo obligated to preserve music videos of the past and present, even beyond the expiration of licensing deals? How can we consider the future of music video preservation with the power of digital distribution in the hands of the “Big Three”? What should be done to preserve music videos from independent labels? [page up]

- Vevo as Music Video’s Digital Archive

- Save Points: Video Games and the Preservation of Play

Video game scholars must continually debate and delimit their object of study. Is a “video game” a subjective instantiation of gameplay? A cumulative collection of these experiences? How do various forms of video game preservation shape video game research methods and scholarship? This panel will attempt to grapple with the various levels of ephemerality, materiality, and interactivity at play within video games and their preservation as media objects. Is it sufficient to preserve gaming hardware and software, without related promotional materials or “feelies,” player-generated mods and skins, etc.? As an interactive medium, preservation is incomplete without play. Beyond discrete objects (digital and material), how do we preserve the experience of play? Is it sufficient to preserve playthroughs, speedruns, and tournament proceedings? If we do preserve them, are contemporary platforms like YouYube and Twitch sufficient? Who might control these potential archives—industry, platforms, academia, libraries, museums, fans, etc.—and to what ends? How will they be cataloged and maintained? [page up]

- In Data We Trust: The Limits of Algorithmic Culture

As platforms like Netflix, Twitter, and WeChat become increasingly imbricated with and valuable to the traditional media industries, the extent to which media production, distribution, and reception are shaped and articulated by (often opaque) algorithms becomes apparent. Similarly, the data collected, coded, and commodified by those same platforms and algorithms create a feedback loop that impacts all dynamics in the current media ecology, from surveillance and recommendations to audience targeting and project greenlighting. How do algorithms and data shape media and media studies? How have industrial practices, processes, and cultures changed in response to the influx of data? How and where is that data being stored, curated, preserved? By whom and to what ends? In what ways and to what extent do data and algorithms increase the precarity of audiences, fans, promoters, intermediaries, below-the-line workers, etc.? Are the effects felt proportionately across all actors and populations? How do age, race, gender, sexuality, and/or industry compound that precarity? How must we adjust our methods and frameworks to account for these shifts and to track these developing trends? [page up]

- Podcasts: Radio Revisited or Audio Reimagined?

As podcasting becomes more securely mainstream, how should scholars refocus our approaches to evolve alongside this media practice? Popular podcasts like Lore, Startup, 2 Dope Queens, and Pod Save America are being adapted for television and other media and scholars face the opportunity to draw historical parallels to these moves while also taking into account podcasting’s digital distribution and customization. This raises the prospect of theorizing the specificity, personalization and intimacy of digital audio media and attempting to craft approaches for studying podcast audiences, creators, and institutions. How do the roles of intermediary institutions like podcatchers, distribution websites and online archives change our scholarship of podcasts? Is there a need for more clear genre distinctions and formal analysis of podcasts and what are the implications of this for how we study podcasting as a cultural and industrial phenomenon? [page up]

- Platforms & Technology

When discussing platforms in media studies, we can think simultaneously of platforms in a new media infrastructural sense, or a more colloquial approach to social media “platforms” on the Internet. The latter version being more commonly represented through Jenkins’ use of convergence culture to describe the spread of media across multiple platforms online. In their 2009 paper, “Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers,” at the Digital Arts and Culture conference, Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort posed several misconceptions in the then-burgeoning field of platform studies. As digital culture continually moves toward application-based and cloud-like infrastructures, it is worth returning to their “FQAs” broadly, and discuss how platform studies can help us to make sense of media’s organizational structures.Of their key takeaways, it was often assumed that “everything these days is a platform,” but such a broad understanding risks misrepresentation of the field. Additionally, they discuss the falsehood that “platform studies is about technical details, not culture.” How can platform studies work as a link between new media studies, digital humanities, cultural studies, and television studies? This question seeks responses dealing with the evolution of platform studies as a field, applications of platforms studies methodologies to traditionally humanistic projects, and explorations of platform studies utility to media studies. [page up]

- In Data We Trust: The Limits of Algorithmic Culture

- The Precarity, Preservation, and Praxis of Sports Media Labor

Sports media labor transpires on the field of play, in the production booths that broadcast the game, in the virtual world of fans on social media, and in numerous other spaces. This labor is beholden to sports media conventions that produce questions about precarious working conditions, the preservation of laboring sporting bodies, and a praxis of resistance within the sports/media complex. What are some of the ways that sports media conventions mirror other industry labor practices that produce precarity? How do sports teams or sports networks leverage contracted work without the traditional benefits associated with full-time employment? How does the term “amateur” in college athletics and the Olympics reflect other classifications of labor that withhold revenue or benefits from workers? How does sports media promote a discourse of care for laboring bodies while discarding those same bodies when they no longer perform as expected or retire? How do the allegories of slavery and indentured servitude maintain their currency for describing racialized sporting labor beyond basketball and football? How do discourses of gender, race, class, and/or ability inform sports fan labor or activist praxis? What other forms of work do athletes, coaches, teams, and sports media makers perform such as affective or political labor? This roundtable invites a variety of responses addressing the precarity, preservation, and/or praxis of sports media labor—broadly defined—in the contemporary moment. [page up]

- It All Becomes Screen History?: Teaching Media Histories

How can you incorporate the teaching of cinema history into broadcast history and vice versa? A number of university and college undergraduate media studies programs are creating entry-level historical overviews that combine analysis of the development of media that we always taught separately in the past – to whit, cinema and television studies. Perhaps radio studies are included as well. What are examples of fruitful cross-pollination? What new overarching issues come to the fore when TV and film production, distribution, exhibition and audience reception practices are compared and contrasted? There are few textbooks available as yet that bridge the divides. What topics would you include? What readings? What major concepts? What student learning objectives? What incorporation of aesthetic issues and industrial structures would be best? How can such a course incorporate issues pertaining to global screens and global audiences? [page up]

- But What About Flow?: Programming Structures in the Post-Network Era

At the time of Television: Technology and Cultural Form in 1974, Williams claimed flow to be “the defining characteristic of broadcasting” (86). Even though television has become a more nebulous technological and industrial medium, flow is still, arguably, an underlying principle in programming and platform design rationales. Williams’ original conceptions dealt with the transformation of discrete programs into a total schedule (from segment-to-segment, to total program, to the night’s programming), but also in the connection between content and advertisements as a singular storytelling product. This panel seeks responses discussing the continued relevance of Williams’ model of flow under new media iterations of television. Or, on how flow is being utilized in contemporary broadcast television scheduling strategies. Possible questions to be explored in this panel: How does the narrative design and reception style of premium cable programs adapt flow? How do Netflix’s and Hulu’s autoplay algorithms replicate the experience of watching live television, and to what purpose? Is flow a useful model to apply to embedded video content in social media feeds? Is flow still a “defining characteristic” of television in the post-network era? [page up]

- What Would A Television Preservation Task Force Look Like?

Scholars of radio history have been engaged for the past several years in participating in a nation-wide program called “The Radio Preservation Task Force” which has sought to locate and identify archival holdings of significant radio recordings, scripts and other historical documents in archives large and small across the US. The RPTF’s focus has been on the non-commercial network aspects of radio, so it has been searching for local and regional collections, especially those involving public service, experimentation, and those representing previously marginalized voices. Can television history scholars create a parallel movement? What kinds of materials would we look for, and where might we find them? Video tapes, scripts, local station management documents, materials from producers, performers, writers and staff camera people, are all possible materials, as are educational programs, local public broadcasting materials, regional sports or advertising materials, and script archives. Finding and possibly guiding the donation of such materials to archives might be the first step in creating a richer and more complex narrative of broadcasting history. This panel welcomes respondents share sources they have located and invites representatives or scholars close to archives (like the Texas Archive of the Moving Image, Northeast Historic Film, and the UT Briscoe Center) to speak on collections they have encountered. As an alternative to traditional Flow position papers at this proposed roundtable, we also encourage media historians to informally present on their found archival materials as a means of idea generation on extraneous archival finds. [page up]

- Changing Channels

In addition to the proposed questions exploring the conference theme, we welcome all papers that address key issues or emergent lines of inquiry within television studies. If you have an idea or a project that you would like to explore at Flow, please submit it in response to this question. This category will function as an “open call,” and panels will be organized based on topic. [page up] - It All Becomes Screen History?: Teaching Media Histories

We know that only small portion of television programming makes it onto commercially-available DVDs, the technology still regarded as the most permanent, shareable, and convenient method of long-term access for libraries and scholars. Soap operas, sporting events, “niche” shows, locally-produced programs and more are unlikely ever to be released on DVD, effectively erasing these objects from the view of future scholars.

But is the outlook brighter for content that does make it onto DVD? The Library of Congress is still evaluating the technology’s long-term stability. Will DVDs endure? Or will the technology prove to be unstable over time, leading to a mass extinction that would further shrink the pool of objects available to study?

An even more challenging picture of the future comes into focus when we shift our attention to born-digital content such as email, websites, web series, social media, and original content from streaming platforms. It is ridiculous to think that Internet providers and media companies will provide access to everything in perpetuity, but how much can be saved? What should be saved? Who decides? [page up]