How Adapting Content to Cultural Expectations Intersects with the Practice of Censorship

Kate Edwards / Geogrify

“Censorship” – it’s considered such a strong, polarizing word in the English language and particularly in the United States where the concept of “freedom of speech” is one of the highest held principles and enshrined in the nation’s Constitution. Censorship is typically defined as the suppression of information which could be perceived as offensive, sensitive, politically incorrect or potentially harmful. This determination is most often made by the institutions that govern a particular locale, such as governments, media, and other local institutions such as the faith system and/or citizens’ groups.

Most of us clearly understand the notion of censorship and would likely all agree that it’s an unwelcome part of any society, especially in today’s plethora of virtual spaces where the flow of information is not only expected but is being perceived as a fundamental human right. Yet over the course of history, institutions have long wielded their power to censor – which essentially means to suppress, alter or enhance information in ways meant to protect the institution’s existence and/or continue to reinforce a particular reality or worldview that is considered most beneficial to the populace.

Censorship usually implies intention, in that certain pieces of information are being enhanced or suppressed for a specific purpose. Whereas propaganda is focused on emphasizing a specific message in order to influence opinion in a desired direction, censorship is almost the opposite: removing a specific piece of content to avoid influencing perception in a certain negative direction.

Cultures have leveraged both censorship and propaganda in their own ways and for various reasons throughout their histories. But one key factor we need to recognize is the difference between censorship and cultural expectations. Censorship most often does connote negativity in purpose but the adaptation of content to cultural expectations can occur for many reasons, some of which may seem like censorship or even propaganda when in fact it’s serving what we construe to be the majority opinion about a fact in a specific locale.

When the South Korean Ministry of Information and Communication complained about the PC-based game Age of Empires and its version of history, and requested a change in order to allow the game to be distributed, was this censorship or just meeting cultural expectation? In the game, the Choson Empire on the Korean peninsula had to fend off the invading Yamato forces from Japan and were overwhelmed, which is essentially what the historical record tells us. The South Korean government strongly disagreed with this “interpretation” of their history, claiming that the Choson people were never overpowered to the degree shown in the game. As a result, a special patch for the South Korean version had to be created that changed history for South Korean players to the degree that the Choson Empire invaded the Yamatos in southern Japan.

For most forms of popular media, governments now maintain some form of ratings board to flag issues that they feel might be particularly problematic along specific categories. Most typically this means reviewing content for the “big three”: sex, violence and profanity, but the cultural sensitivity to each of these areas varies widely from locale to locale. For example, South Korea’s Game Ratings Board (GRB) didn’t exist when the Age of Empires issue occurred but today it’s known to be particularly attuned to the “big three” as well as any political and cultural nuances that may portray South Korea in a negative light. In the U.S., there’s the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB), and for Germany the Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle (USK), the Pan European Game Information (PEGI) system for Europe, and the Video Standards Council (VSC) in the U.K. – just to name a few. For film, there’s a wide variety of ratings bodies, such as the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) in the U.S. and the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) in the U.K.

Some would argue that the role of these bodies is to effectively act as censors, working to extract content from creative works that may be deemed harmful or sensitive to consumers and/or otherwise negatively reflect the local culture (such as the use of blatant cultural stereotypes). From the viewpoint of the ratings boards, it’s a matter of tailoring content to local expectation. However, it’s critical to highlight the fine line between careful tailoring and blatant suppression. Culturalization is focused on preserving the core intent of creative content and simply ensuring it’s compatible with local customs and expectations. Censorship takes another turn towards an active suppression of facts that may remain relevant to a culture but for various reasons, the central authority may want to ignore those facts for their own purposes.

One of the more controversial examples has been the ongoing tendency of the Japanese government to rewrite their history textbooks to modify certain aspects of their imperialistic past, particularly as related to World War II. In Japan, textbooks go through a rigorous process of review by the Ministry of Education to ensure that it meets specific standards and guidelines. In recent years, the government has faced increased criticism around their supposedly objective review process, wherein textbooks which negatively portray Imperial Japan and its aggression during World War II are rejected, partially under pressure from the more conservative government. In 2000, a group of right-wing scholars produced the “New History Textbook” which put a positive spin on Imperial Japan’s actions and drew considerable backlash from inside Japan and beyond. In June 2007, over 100,000 people protested in Okinawa after the Ministry of Education suggested that the Japanese military’s role in forced suicides in 1945 on Okinawa be deemphasized for the history books. And the controversies around revisionist history in Japan have persisted since. This type of revisionist move by Japan evokes calls of censorship as well as generates backlash not only from Japanese citizens who desire a truthful rendition of history but also from countries that were affected by Imperial Japan’s actions, most notably China and South Korea.

Is the historical revision of Japan’s role in World War II a case of cultural tailoring or blatant censorship? Based on the reactions even within Japan, it could be concluded as a clear case of factual suppression. This then calls attention to the issue of how one gauges “majority” opinion and what constitutes a case of censorship. In most of the cases I’ve ever dealt with in creative content, it was an issue of very specific, surgical tailoring to ensure that a single content element doesn’t set off a wave of local backlash. And in most of these cases, it was related to deeper cultural sensitivities such as religious faith, ethnicity and cultural stereotyping.

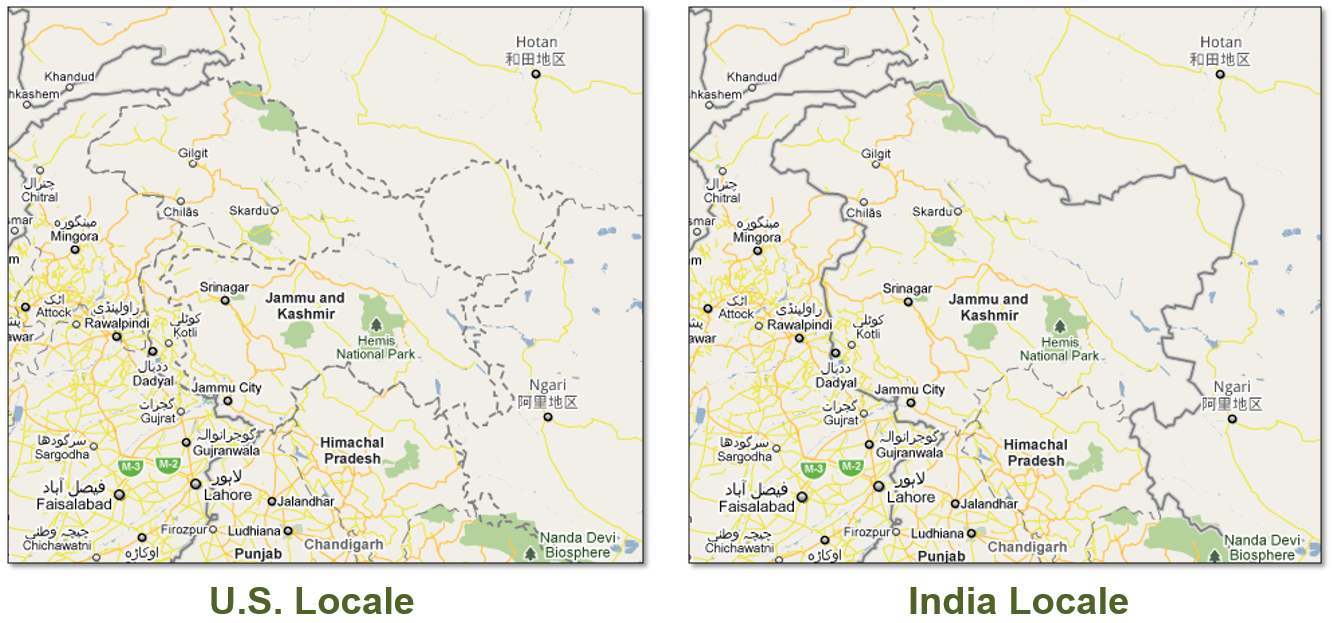

However, some types of content lend themselves quite easily to censorship, mainly because they are so closely tied to government messaging and/or perception of government control. Probably the best example of this would be the use of maps in information products. Sometimes the map must be tailored to meet the widely-accepted local expectations, but more often the maps are revised for local consumption due to a government’s strict policy on how their territory must be displayed. If you ship a product to India that doesn’t show all of the disputed Kashmir region as Indian territory, it will be censored. If you ship a map to China that doesn’t show Taiwan as part of greater China, it will be quickly censored. Part of the impetus depends on how tightly the government desires to control the message of the content, and with the visual nature of maps and the government’s desire to reinforce their perception of territorial sovereignty (what I call their “geopolitical imagination”), blatant suppression is the only way they see to limiting exposure to an alternative viewpoint.

For those of us who create content, and especially those responsible for global distribution, we need to remain very cognizant of our decision-making and strategy – whether we are carefully tailoring to positively meet expectations or if we are serving the cause of local censorship because of government restrictions. This is a core dilemma for many multinational businesses; at which point will a business decide to not cross a line, effectively the “moral compass” of the company? There is no easy answer to this question and it varies from company to company.

Image Credits:

1. Censorship is a contentious political issue.

2. The invasion of the Choson Empire by Yamatos in Age of Empires. (author’s screen grab)

3. The ratings assigned to games in the U.S. by the ESRB.

4. Newsweek cover story on Japan’s revisionist history.

5. Depictions of Kashmir region in Google Maps. (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

That’s i have searched a most useful site, here we can learn how to set printer in windows 10 os , there is no required any charges and account sign.