Women Together, Not Alone: An Alternative Feminist Legacy for The Mary Tyler Moore Show

Bonnie J. Dow / Vanderbilt University

I admit I was surprised by the volume and intensity of the commemorations around the death of Mary Tyler Moore in late January. What precipitated so much attention to the loss of a former television star who had been so little in the news for years? Was it our hunger for all things retro? A longing for a simpler time, when our television heroines were more iconic because we had so much less television than we do now?

As my inbox populated with media requests for commentary on how Mary Richards, Moore’s character on The Mary Tyler Moore Show (MTM) from 1970-1977, “revolutionized women on television” (as one query put it), one explanation I settled on for this phenomenon was the context created by the recent Women’s Marches across the nation. The outpouring of political resistance by women, and the ample media coverage of it, was certainly reminiscent of the 1970s. Perhaps the desire for discourse around MTM was about a collective need to celebrate feminist achievements from the past at a time when women’s rights are under assault.

January’s Women’s March was strikingly analogous, in fact, to 1970’s Women’s Strike for Equality, the largest public action of early U.S. second-wave feminism. On August 26, 1970, less than a month before the September 1970 premiere of MTM on CBS, the Strike involved an estimated 50,000 women who marched up Fifth Avenue in New York City, and, as in January, there were satellite marches in cities around the country. The marches merited coverage on all three nightly newscasts as well as front page, above the fold, coverage in the New York Times, providing useful feminist context for MTM, a show that producers wanted to be understood as a “new” kind of female representation. [1]

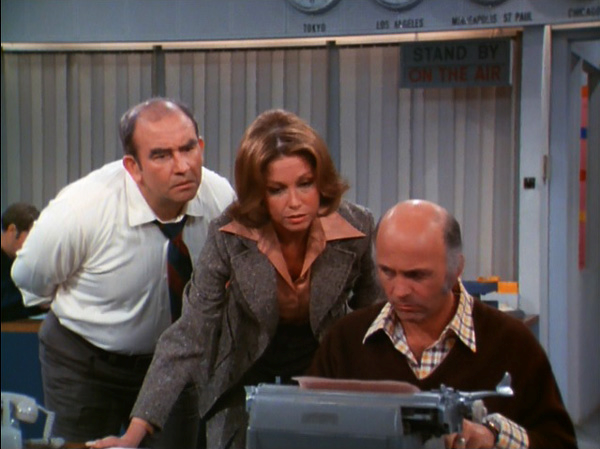

In another useful coincidence, one of the three demands of the Women’s Strike for Equality, along with abortion rights and child care, was equal opportunity in employment, an issue raised in the first episode of MTM (“Love is All Around”). When Mary Richards interviewed for a job in the WJM-TV newsroom, her soon-to-be boss, Lou Grant, told her he assumed it would be filled by a man. Later in the episode, her new colleague, newswriter Murray Slaughter, referred to her as their “token woman.”

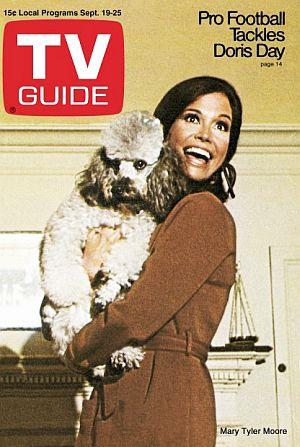

Although the episodes of MTM that dealt explicitly with feminist issues—like Mary’s demand for better pay or her attempt to hire a woman sportscaster—were not that numerous, the show’s departure from previous sitcoms populated by submissive wives and mothers or frustrated husband-hunting single women made it the new standard for liberated TV womanhood in the eyes of mass media. The title of TV Guide’s story on MTM the week it premiered was “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby,” which gestured at the infamous Virginia Slims ads that equated smoking with women’s liberation while pointing out Moore’s transition from suburban wife and mother in The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-1966) to single, urban career woman in MTM. [2]

When Murphy Brown (1988-1998), another sitcom centered on a woman in a television newsroom, premiered in 1988, the comparisons to MTM were remarkably consistent. On the one hand, such comparisons pointed out that Murphy Brown was a much more explicitly feminist character, a “Mary Tyler Moore Updated for the Eighties,” as a USA Today headline put it. [3] On the other hand, these comparisons also made clear that MTM had positioned the “single, white [urban] working woman sitcom as the paradigmatic form for feminist representation”. [4] And that is why we have had so much media commentary over the years on the feminist implications, or lack thereof, of not just Murphy Brown, but also Sex & the City (1998-2004), 30 Rock’s Liz Lemon (2006-2013), and, most recently, Girls (2012-present).

Shortly after Moore’s death, Lena Dunham, creator and star of Girls, penned a New Yorker column titled “Everything I Learned from Mary Tyler Moore,” in which she said this: “There was a lilting poetry to her expressions of exasperation, a performative melancholy to her solo moments that is familiar to any woman who has ever lived alone, and a strident glory when she finally stood up for herself. Imagine her at last weekend’s Women’s March—pumping a fist despite herself, but too prudish for a pussyhat”. [5]

In addition to the reference to the Women’s March, two implications of Dunham’s remarks stand out to me. The first is the emphasis on relatability. Mary Richards was a user-friendly feminist representation for those not entirely comfortable with women’s liberation, because, although she had moments of feminist frustration, she was incapable of being truly rude. This made her tremulous and more than a little bit funny when she tried to resist sexism, as in Season 3’s “The Good Time News,” in which she tried to confront Lou Grant after discovering that she was paid less than the man who had previously held her job.

Especially at the time, watching a good girl trying not to be one was comedy genius, and a key reason MTM was so beloved. But that’s not what gave the show its feminist resonance for mass media or the public. More than anything, Mary Richard’s feminist significance came from the fact that she was alone, the second crucial implication of Dunham’s comments. Alone, in television parlance, meant “without a man,” demonstrating how profoundly the medium’s representations of feminism were conditioned by heteronormativity. I called this “lifestyle feminism” twenty years ago, but the crux of that lifestyle, as it manifested in MTM and other shows to which it was compared, was lack of a heterosexual relationship—the career and the always urban setting were just window dressing. [6] This is what made MTM different from other shows that explicitly addressed feminist issues—like Maude (1972-1978) or Roseanne (1988-1997)—but that have gone largely unmentioned during the many reflections on Moore’s feminist legacy.

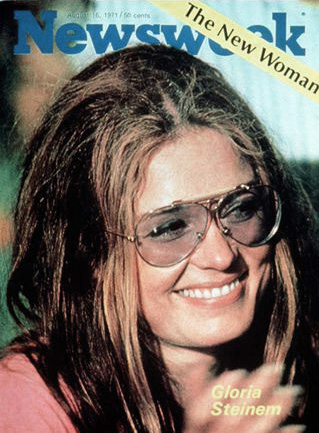

As much as this limited understanding of feminism is a problem for television, it is also a problem for feminism itself. A central reason mass media made Gloria Steinem the feminist icon for the 1970s and beyond was because of her long-unmarried status, and her famous quips about it, e.g., “a woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle.” Indeed, Steinem’s public career as America’s foremost feminist gained steam at about the same time as MTM did. Despite Steinem’s own support for lesbians and women of color from the beginning of her feminist work, the white, heterosexual (but uncoupled), career woman became the somewhat universal signifier of feminist womanhood.

The lamentations about feminism’s failures to be diverse, inclusive, and intersectional have been going on for decades, and I need not rehearse them here, except to say that the entire fault is too often laid at the feet of (white) feminists themselves when it was mass media that provided the American public with profoundly narrowed versions of feminism from the start. [7]

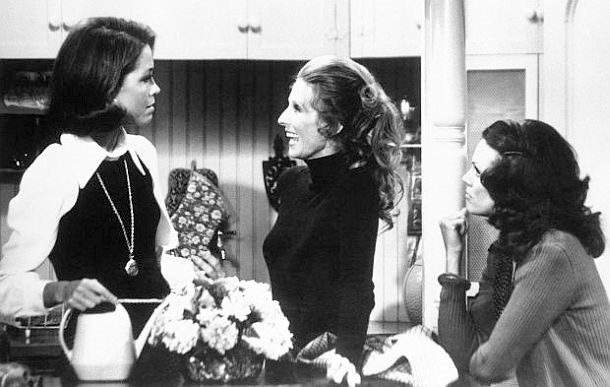

The white, urban, single career woman is a problematic feminist figurehead, and not simply because it limits our understanding of the multiplicity of women who figure in feminism. This formulation also overlooks a crucial component of feminist politics: its collective nature. Feminism is about women together, not alone, and that is one of the legacies of MTM that should be celebrated more. Mary Richards had a female—although not always feminist—community, a key reason she was actually not alone. For the show’s first three seasons, her best friend Rhoda Morgenstern, a Jewish New Yorker transplanted to Minneapolis, brought some noteworthy diversity to the sitcom and provided a comic foil for Mary’s Midwestern propriety. Mary’s landlady, Phyllis Lindstrom, a frustrated housewife, was also part of Mary’s community at home, where much of the show’s comedy occurred.

Of course, Rhoda and Phyllis provided solidarity at home, not at work, where Mary remained a token. Indeed, female solidarity would have been much more threatening in the workplace, as it always is in the public sphere. But to claim that Mary Richards was a pioneer because she was a woman alone makes invisible the importance of women’s relationships to each other: in life, in television, and in feminism. Their strong female communities are the most compelling reason, for me, that Sex & the City and Girls are heirs to MTM. Because if Mary had been here to throw her pink pussyhat in the air last month, she would not have done it alone on a downtown street—she would have been in a crowd of women doing the same.

Image Credits:

1. Mary Tyler Moore as Mary Richards in The Mary Tyler Moore Show

2. Lou Grant, Mary Richards, and Murray Slaughter in the WJM Newsroom

3. TV Guide cover, September 19-25, 1970

4. Gloria Steinem on the cover of Newsweek, August 16, 1971

5. Mary, Rhoda, and Phyllis on The Mary Tyler Moore Show

Please feel free to comment.

- Bathrick, Serafina. “The Mary Tyler Moore Show: Women at Home and at Work.” MTM: “Quality Television.” Eds. Jane Feuer, Paul Kerr, & Tise Vahimagi. London: British Film Institute, 1984. 103-104. [↩]

- Whitney, Dwight. “You’ve Come a Long Way, Baby.” TV Guide. 19 September 1970. 34-38. [↩]

- Quoted in Alley, Robert S. & Brown, Irby B. Love Is All Around: The Making of The Mary Tyler Moore Show. New York: Delta, 1990. 204. [↩]

- Dow, Bonnie J. Prime-Time Feminism: Television, Media Culture, and the Women’s Movement Since 1970. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1996. 137. [↩]

- Dunham, Lena. “Everything I Learned from Mary Tyler Moore.” The New Yorker. 27 January 2017. [↩]

- Dow, Prime-Time Feminism, 24. [↩]

- Dow, Bonnie J. Watching Women’s Liberation: Feminism’s Pivotal Year on the Network News. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014. [↩]

Gloria Steinem is my one of my favorite person. My grandmother read this magazine when it was released from Newsweek. She kept it in her magazine shelf. By this way I got this magazine.

Thanks Bonnie Dow for sharing this article after a long time.

The death of Mary Tyler Moore was a moment for sober reflection. My first thought was actually about the film “Ordinary People” where she plays a not so great mother. I feel that she was as melancholic there as much as she was in her eponymous TV show.

Thank you for the excellent speedypaper review! SpeedyPaper really helped me in writing my paper. I received A and I am very happy because of that. My teacher was pleased with my work. I will recommend you to all I know.

Some people cannot help but project a certain image. MTM may not have been as ardent a feminist as people may have wanted, and she did seem to have become a bit more of a “conservative” towards the end of her life:(her support of John McCain and Fox News), but her two unforgettable tv personas will always stamp her as a positive and pro-active feminist agent for change…even if the actress herself didn’t necessarily want that.

Public speaking is our topic today and my teacher changed my technique into mentioning the nuances in wording which could absolutely have an effect on the way to set up a hassle free performance. Today turned into a amazing teaching and I looked forward for subsequent week’s evaluation. Thanks arts columbia.

Thank you for the excellent speedypaper review! SpeedyPaper really helped me in writing my paper.