Magical Girl as a Shōjo Genre and the Male Gaze

Coco Zhou / McGill University

In my last column, I provided a brief overview of the extent to which the shōjo image has come to dominate all aspects of contemporary Japanese visual culture. I also suggested that this image is constructed to invite men to not only objectify her but also identify with/as her. I would like us to take a closer look now at the ways in which this dynamic is produced. When they look at these representations of girlhood, do girls and boys, men and women all see the same thing? How does a piece of shōjo media frame viewers to look at it a certain way, and what kind of gendered expectations and demands does it make on the viewer?

Although the shōjo character in anime and manga enables viewers of all genders to consume her as a commodity, she also embodies a kind of freedom from social constrictions by virtue of being non-reproductive. Focusing on this liberating aspect of being shōjo, by the late 1980s artists had begun to produce stories about shōjo subjects who are embedded in narratives around battle, adventure, and high technology.[1 ] These anime/manga are consumed by audiences across the gender spectrum and feature a variety of shōjo representations. Narratives about the shōjo in 1990s pop culture thus appear to adopt male (shōnen)-associated elements, such as action, violence, and responsibility toward society.[2 ]

Just as these depictions of shōjo repudiate earlier ones that signified irresponsibility, weakness, and passivity, these new images of “female empowerment” also contradict the social realities of Japanese women.[3] Among all of the visual productions and practices that helped spread these shōjo images, I want to focus on a particular anime/manga genre, the Magical Girl (mahou shōjo), and argue that male viewership and subjectivity are deeply wedged into this genre that simultaneously targets a young female audience.

The mahou shōjo story is most commonly identified by transformativity, a central trope of the genre. The typical protagonist is an ordinary girl who is suddenly granted special powers, which she activates after performing a series of ritualized gestures, often involving a catchphrase and a personalized costume. This ability to transform, though also shared by various types of shōnen media (that which targets boys), is unique to the mahou shōjo in the sense that it is ontological in nature: while shōnen comics may include combat scenes in which the hero uses high-tech body armour to turn himself into a robot warrior, the Magical Girl’s transformation seems to originate internally.[4 ]

Consider Sailor Moon (1991) and Cardcaptor Sakura (1996), the most commonly cited mahou shōjo productions in the past two decades. We could identify elements of shōnen in both of these works, not only in their emphasis on combat and protecting society from evil, but also in their elaborate transformation sequences, in which the heroines transform by donning special fighting outfits.

While this transformation is sexualized, what ultimately makes the Magical Girl shōjo is the fact that she refuses to activate her sexual potential despite all her power. Whereas the antagonists in both series are often power-hungry seductresses with thick makeup, Sailor Moon and Sakura are marked by youthfulness and cuteness, signified by their frilly skirts and school uniforms. Despite her resistance to womanhood, the mahou shōjo is tasked with domestic obligations. Sailor Moon’s later series focuses heavily on the family relationship between Sailor Moon, her future husband Tuxedo Mask, and their time-travelling daughter. Meanwhile, in Cardcaptor Sakura’s motherless household, Sakura fulfills the cleaning and cooking duties assigned to her. The Magical Girl image is thus constituted by her social and communal usefulness.

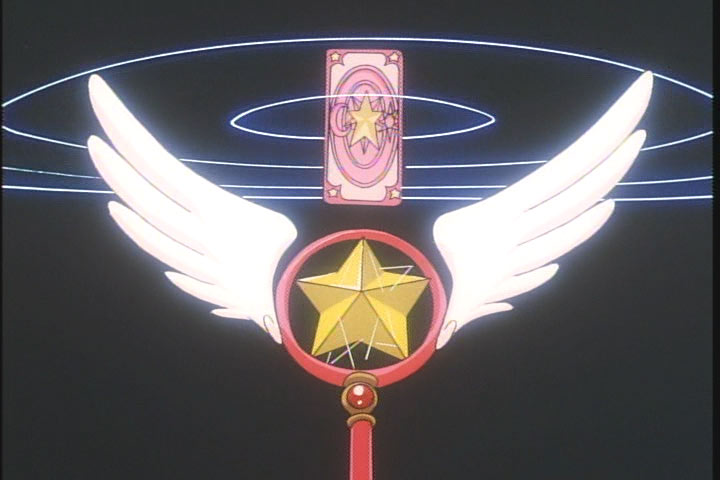

We are beginning to see how these paradoxical messages may be useful for reproducing patriarchal gender relations. On one hand, the mahou shōjo is supposed to prepare herself for conventional womanhood, and on the other hand, she is told to stay shōjo, since her “power” is not only associated with cuteness, femininity, passivity, but also stems from those concepts of powerlessness. Another way in which mahou shōjo productions usher young children into adopting gender norms is through their business structure. As Japan’s production system of animation depends financially on the sales of copyrighted goods, the Magical Girl genre’s backbone consists of exploiting viewer interest specific to young female children, the targeted consumers of its merchandise. The same transformation sequences are often repeated every episode, recycling fragmented shots (of a magical staff, for example) to effectively show details of the toy, thereby making it attractive to potential buyers.[5 ]

By carefully exploiting feminine ideals and consumer interest, mahou shōjo productions have thus become a site of contradictory and prescriptive ideas surrounding gender roles and identities. But how does the mahou shōjo traffic male subjectivity? For one, eroticization and objectification are inherent in the transformation sequences, as they not only portray commercial goods in fragmented shots but also spatially dissect the transforming female body. In addition to commodifying her, male viewers are also invited to identify with the mahou shōjo who, despite being secretly powerful, is carefree and disengaged from expectations of masculinity. Since her power is constituted by her shōjo identity, the mahou shōjo does not need outside forces in order to be powerful, which makes her an appealing object of consumption (and identification) for post-economic-collapse Japan.

At the same time, masculine ideals are reaffirmed by the glorification of violence—through action-driven plots and elaborate battle scenes—and by the relationships between Magical Girl characters, which simulate structures of male competition. Much like the way patriarchy creates solidarity among men at the expense of women, the world of mahou shōjo seems to exclude men so that Magical Girls could enjoy competing with each other as a way to build meaningful relationships. This type of rivalry also channels desire. [6 ] Subjected to the male gaze, battle scenes between Magical Girls are performed so that men could not only eroticize the relationships between the characters but also identify themselves in them. Should the practice of referring to these battle scenes as “fan service” be of any indication, male viewership is clearly taken into consideration in the production of mahou shōjo anime, if not prioritized.

The mahou shōjo thus generates and reconfirms gender norms and heteronormative relations, using the motif of magical transformation—masked as empowerment—to exploit its subjects and mediate feminine ideals. The visual conflation of a shōjo body with power also invites the male audience to both eroticize her and identify with her. Though this identification stems from anxieties about and resistance to traditional masculinity, it is ultimately enabled by patriarchal hegemony, the power structure against which the resistance is intended.

Image Credits:

1. Sailor Moon

2. Cardcaptor Sakura’s Staff

Please feel free to comment.

- For instance, many of Miyazaki Hayao’s films adopt this very formula: Nausicaa (1984), Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), Princess Mononoke (1997), and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away (2001) all centre around silly yet brave shōjo heroines on a mission. Shirō Masamune’s Ghost in the Shell (1989) and Takahashi Rumiko’s Ranma ½ are also part of this trend. [↩]

- Orbaugh, Sharalyn. “Busty Battlin’ Babes: The Evolution of the Shōjo in 1990s Visual Culture.” Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field (2003). [↩]

- Saito, Kumiko. “Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis: Magical Girl Anime and the Challenges of Changing Gender Identities in Japanese Society.” Journal of Asian Studies 73 (2014). [↩]

- Orbaugh, “Busty Battlin’ Babes,” 215. [↩]

- Saito, “Magic, Shōjo, and Metamorphosis,” 154. [↩]

- Eve K. Sedgwick, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985). [↩]

Pingback: Images of femininity in Sailor Moon and the role of merchandise (part 2) – The Painter of Postmodern Life