When Sleepers Wake and Yet Still Dream

Melinda Barlow / University of Colorado at Boulder

from all thought

a clean break

in blank space

Neither cowboy nor oilman, hardly a giant and more like a ghost, Travis Henderson dreams his way into West Texas oblivion, then runs from dawn to dusk to get there. A haunted man on the lam from his own memory, he wanders in a desert as vast as the hole in his heart, armed with a tattered photograph of a vacant lot he bought in the town where he may have been conceived and hoped to raise his son. But when the wife he shackled with a cowbell and belted to the stove finally managed to flee, he left fatherhood behind, burying it inside. Only after his brother retrieves him four years later following a collapse in the blinding light of Terlingua does he begin to see what being a father really means.

Mute and melancholy, Travis is the antithesis of Texan flamboyance. No swagger or slang; uninterested in style; incapable of telling tall tales and devoid of sweeping ambition, his is not a larger-than-life personality but rather a diminished late 20th-century masculinity—in the opening shots of Paris, Texas, he is but a speck within the frame. Anxious, uncertain, and shorn of vanity; unsure how to bear the mantle of paternity, deal with loss of potency and pending mortality, and definitely not in assignment service any condition to fight, Travis, and the fellow troubled men who precede and succeed him in many mid-20th through early 21st century American films, nonetheless does battle, and, in the quiet epic of his own life, as it unfolds in the elegy for the American West which is Wim Wenders’ film, ultimately makes a single monumental gesture. He restores an estranged mother (his former wife) and son. Until then, as with his equally apprehensive onscreen counterparts, his duel lies deep within.

What is the appeal of the pose that Travis eschews, and that a relatively unconflicted man like Bick Benedict (Giant, 1956) adopts so effortlessly? That Hud Bannon (Hud, 1963) appears to embody? That Jack Burns (Lonely Are the Brave, 1962) clings to with tenacity, while fending off modern technology? That Joe Buck knows is intimately bound up with his clothes (Midnight Cowboy, 1969), and that revisionist westerns routinely dismantle? What pleasures and paradoxes are expressed through the image of the cowboy and his costume? What are the ideological stakes of this form of male masquerade?

Clothes, as they say, make the man; they also allow boys to envision themselves as potent masculine images: as stylish, heroic fighters of custom dissertation headed straight for the OK Corral. But images may be deceiving, and by 1960 American westerns know this. Says an extra playing one of Davy Crockett’s men in John Wayne’s The Alamo when he first sees dashing General Santa Anna, “Fancy clothes don’t make a fightin’ man,” and even Colonel Travis (Laurence Harvey), tired of The Duke-as-Crockett’s hokey adages and exaggerated vernacular, quips “All that bad grammar is a pose.”

No image is more striking or more deceptive than that cut by tough as a boot Hud Bannon, a cowhand as mean and unprincipled as his father Homer is venerable and hardworking. Instead of shooting their entire herd of cattle when it is infected with foot-and-mouth disease—any rancher’s worst nightmare—Hud wants to sell it, before it’s too late. Homer can hardly believe such an unscrupulous man is his son, and warns nephew Lonnie that Hud’s charm is nothing but a sham, and one with national implications: “You think he’s a real man. But you’ve been taken in our service at http://samedayessays.org/case-studies-online/…Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire.”

When Kyle Hadley, alcoholic heir to the Texas oil company run by his father Jasper, a successful “big man,” is told by his doctor that his test results show a “certain weakness,” a classic moment of Sirkian mise-en-scène expresses his humiliation at the possibility of impotence, as Hadley walks by a young boy vigorously bouncing up and down on a mechanical horse. Even more significant is the fear he describes to wife Lucy upon awakening from a fevered dream: “It’s like I was deep in a mountain pass, snowcaps hanging over my head. If I make a sound, snow might all come tumbling down. Bury me—alive.”

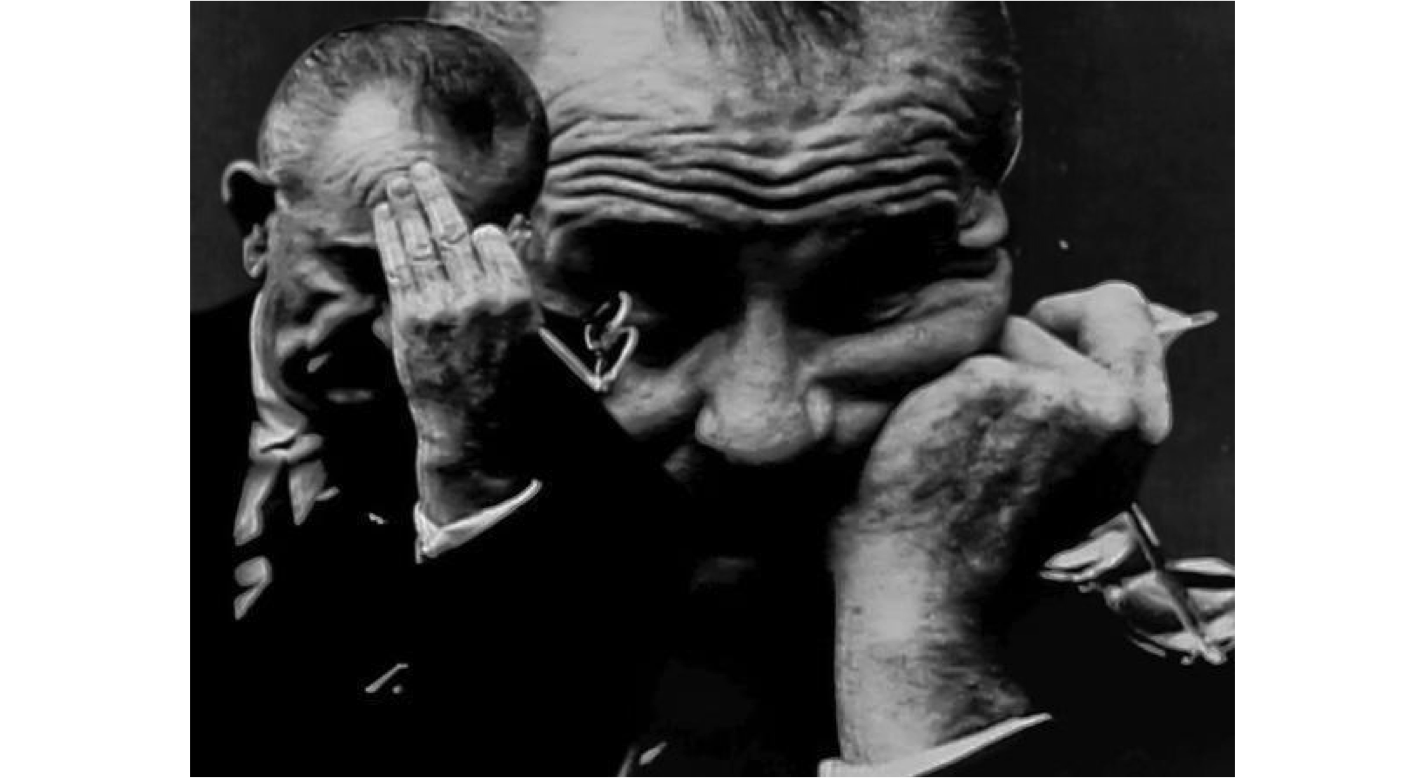

In the President’s dreams, we are told, his words become “distorted and undefined,” his sentences barely trip off his “swollen and uncooperative tongue,” and his talk becomes incomprehensible—mushy and doughy. When he finally loses his voice and compensates aggressively, imagining an imposter who delivers his speeches with the utmost eloquence, he also dreams of a stampede of cattle charging him at great speed, rendered in the film as a blank screen onto which we project our most terrifying visions of what such an assault might be like. An anxious big talker who was a product of the poverty of the Hill Country— afraid of ending up penniless, just like his father—in The Rancher, Johnson becomes a man unhinged, the “credibility gap” associated with his late presidency a function of the distinction between his public persona and his unconscious private life.7

An aged man is a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress

There are things we don’t know. We yet still dream.

1. Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984).

2.Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984).

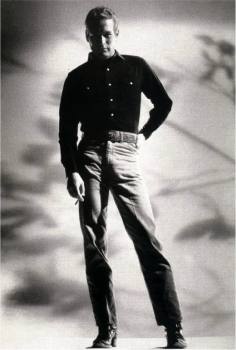

3. From left: Found photograph, Austin, Texas. Collection of Melinda Barlow. Paul Newman in production still for Hud (Martin Ritt, 1963).

4. Jon Voight as Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1969).

5. James Mason as Ed Avery in Bigger Than Life (Nicholas Ray, 1956).

6.Dorothy Malone as Marylee Hadley in Written on the Wind (Douglas Sirk, 1956).

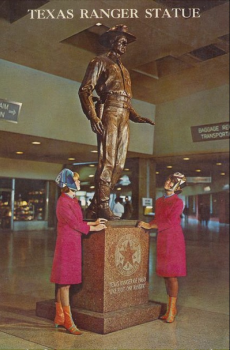

7.From left: Postcard of The Texas Ranger of 1960. Collection of Melinda Barlow. Postcard for The Trailer (2013-ongoing) by The Bridge Club. Photo credit: Matthew Weedman/Artisan Photo.

8.“What Remains,” (The Bridge Club, 2013), detail. Photo credit: Matthew Weedman/Artisan Photo.

9. The Rancher (Kelly Sears, 2012).

10. Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978).

Please feel free to comment.

- Jean Baudrillard, America, Trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso, 1988), 9. [↩]

- Robert Warshow, “Movie Chronicle: The Westerner,” in Film Theory and Criticism, ed. Gerald Mast and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 449. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Art Spiegelman, “Mein Kampf,” New York Times Magazine (May 11, 1996), 37.

Courtney Fellion’s Honors Thesis, “Heroes and False Prophets: Why the New American Western Doesn’t Believe Any More” (University of Colorado, 2008), opens with a lovely meditation on the personal and cultural significance of a “found” image of an “unknown” cowboy she discovered in a family scrapbook. [↩]

- Vito Russo, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (New York: Harper & Row, 1981), 81. [↩]

- Barbara Welter, The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1960,” American Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 2, Part 1 (Summer, 1966), 152.

The other irony of this image is that the sculpture, whose official title is Texas Ranger of 1960, was created by Schulenberg-born artist Waldine Amanda Tauch, whose teacher Pompeo L. Coppini told her early on that she was “too small” to be a monumental sculptor. Her answer: “That’s what I started out to be and that’s what I’m going to be.” See University of Texas at San Antonio Digital Library, “Interview with WAT, 1983”, p.6. [↩]

- For more on Lyndon Johnson’s driving fears and anxieties, see Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982). [↩]

Melinda,

I really enjoyed your piece and the way in which you weave together a variety of images related to the idea of the cowboy and late 20th/early 21st century masculinity in crisis as well as the way you explore the strength and fragility of the women in Sirk’s melodramas and in the art created by The Bridge Club. There is something about the wide open spaces of the West, that while enduring and liberating in some ways can also hide dark secrets of their own. I am particularly taken by the power of the image of the cowboy and the idea that the “clothes make the man.” My maternal grandfather had many lives and many identities. Although he grew up on a ranch, he also served in the Korean War and spent the majority of his life first as traveling salesman for companies like French’s mustard, and then as a used auto salesman. Towards the end of his battle with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease), he also became a born-again Christian. However, at his funeral most of the focus was on my grandfather as a cowboy. The preacher wore my grandfather’s leather jacket, and his hat and a saddle were on display. Not mentioned was the fact that my grandfather was at least 1/4 Cherokee, causing my mom to joke that one “can’t be remembered as both a cowboy and an Indian.” When I moved to Austin from Denver, Colorado, the first thing I bought was a pair of cowboy boots. Knowing the purchase a cliche, I still longed to don a costume that would make me feel somehow more authentically “Texan.” Even if cowboy boots have become the providence of hipsters, the longing behind wearing them–to be tough, wild, and free–lingers on.

It was a pleasure to read your work!

Thanks,

Natalie

Melinda,

Excellent piece! The themes of fathers, masculinity and the west are woven beautifully together. I particularly enjoy the still of DAYS OF HEAVEN, albeit one of my favorite films, its inclusion highlights the landscape of the west as a father figure in its own right. The glow of Malick’s magic hour cinematography alludes to the balance of the American Dream and of the personal dream of the idealized masculine father.

The documentary HARRY DEAN STANTON: PARTLY FICTION does a fantastic job exploring the life of the actor and why he himself is Travis of PARIS, TEXAS. A loner in his own right, spending a life within the Hollywood system, but continuously rebelling and forging his own path in a quite, fringe manner.

In contemporary pop culture, this reminded me of MAD MEN. Don Draper as the mysterious, stoic paternal figure with a hidden past, using these traits to his advantage by creating “dreams” of American consumerism through advertising.

Matthew Campbell

Programmer

Denver Film Society

Hello Melinda,

Your article is pointing out one of the main features of the contemporary American civilisation : the American myth of the hero, as if the word hero substitutes to the word god…according to my humble perception of it and from what I have perceived from living in the US (6 years ) twenty four years ago. But the way, my native language is french and, please, excuse my poor english.

The hero is supposed to be a handsome man; when I arrived in America I was impressed by the high number of good looking men : handsome faces, nice strong bodies, nice features, cool and nice guys. When I was a child in the 60ties I used to watch like crazy the TV show called “Joss Randall” (name of the show on the french TV programs), the hero was a “chasseur de primes” (bounty hunter ….?) and the actor was ….Steve McQueen!

And I grew older, fortunatly, because I discovered new cowboy movies like Blazing saddles or Brokeback mountain, I loved them, like my favorite TV shows as a child, or the “grands classiques”..

I guess I am naïve and I have a tendency to believe in the picture, and I am not really looking for what the picture is hidding… I like a hero because he is funny, handsome or tender, whatever… I am excited when I am going to watch a nice cowboy movie, like the greeks and the romans, two thousand years ago, could not believe their own eyes as watching the monstruous painted statues of their gods…

What we see is an illusion after all…who wrote that? ; ) Ah! By the way (I did like Natali ), I bought a pair of cowboy boots two weeks before I come back to Paris for good! But I found myself so stupid wearing them in Paris that I never used them and I finally threw them away…oups!

Thank you for this great article that French “cinéphiles” would love to read for sure!!

Jean-Luc Briastre

Thank you Dr. Barlow for this multi-faceted article. The question that arises for me is how do films, especially Westerns, strike a chord with our individual imaginations “to serve our dreams of an America that never really existed?”

The dreamscape that the Western creates isn’t just a part of the American collective consciousness. The idea of the “Wild West” that has been created over the years by films may not be entirely American.

Although I was born in Colorado and I have seen real cowboys, ghost towns, abandoned gold mines, mountains and desert, the mythic West I dream of is in fact thousands of miles away.

Behind the house I grew up in, there was a tall wooden swing set in the corner of my large backyard. As a child, I used to swing so high that I was able to see over the top of my neighborhood to another community several miles away. From this view, I thought I could see into the other side of the world. At a distance, these houses with terra-cotta roofs and their surrounding pine trees became ancient villas and cypress groves.

The first cowboy movie to grip my imagination was Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More (1964). I even learned to play the jaw harp so I could accompany the film’s opening theme song written by Ennio Morricone. This film like many other low budget cowboy flicks stampeding cinemas in the 1960’s, were filmed in regions all over Italy and Spain. Although these films featured a multicultural cast, the majority of the directors and producers were Italian, hence the term “Spaghetti Western.” In the early Italian film industry, dubbing a motion picture was a typical practice. For this reason, these films could be enjoyed internationally. Clint Eastwood could flawlessly speak English and Italian.

While I was dreaming of desolate villages in Andalusia and Sicily, Europeans envisioned the Wild West as an American setting proper; a place far away, dangerous, and exotic. For Europeans, the American frontier was a place of adventure before the arrival of the Spaghetti Western. One example of European taste for cowboy culture is the longevity of the Italian comic book character Tex Willer created by Gian Luigi Bonelli and Aurelio Galleppini in 1948. Within the introduction to his novel Io Non Ho Paura (2001), Italian author Niccolò Ammaniti resurfaces childhood memories of reading Tex and playing cowboys in his yard. For Ammaniti, these memories help him to recreate a child’s struggle to distinguish adventure from danger when one is seduced by imagination.

The examples Dr. Barlow provides in her article are portraits of the chronically seduced in which mature men must distinguish myth from reality within their own lives and identities.

How do play, how do we dream, and how do we imagine the West? The real wild frontier or the imaginary might exist in your own back yard.

Kate Faulk

MA Candidate

Department of Art History

University of Wisconsin-Madison

From the man drowning in oblivion, the shadow of masculinity looms in the cemetery of unburied traumas. Shackling the wife ( Paris,Texas) appears as a last gasp of possession, as the women in this meandering meditation undo their shackles and leave the men behind, in drag.

This essay brings up Joseph Campbell’s hero of a thousand faces, however, here we see the thousand melting faces of masculinity in a series of protagonists stripped bare of their brutality, left with only a silent primal scream–as seen in the haunting image from Bigger than Life. Women like Marylee Hadley in Written on the Wind seem to be the caretakers of this mausoleum of male dreams.

Like those who have commented above, I have my own relationship with cowboy ideology. In my youth I starred in the play Calamity Jane (some of you may know the campy Doris Day film). The whole concept of the play is to strip Calamity of her masculine traits and garb, and transform her into a “woman.” This is done through a musical number titled a “Woman’s Touch,” in which she learns how to clean her house and cook. As an adolescent I loved wearing my fringe leather cowboy outfit, tipping my hat to ladies, holstering up my pseudo-pistol, and swaggering in my cowboy boots. After reading this piece, I realized how much I enjoyed embracing my inner John Wayne and the power that the outfit and the facade of masculinity made me feel.

I also enjoy The Bridge Club’s active rebellion against the monumental forces of masculinity as illustrated in the photograph. Rather than staring at the statue, enamoured, they stand its shadow in the only vibrant patch of grass while the rest of the environs, perhaps like Sam Houston’s power, withers away.

Thank you Melinda for continually inspiring me,

Helena

Fascinating read that weaves traditional cowboy imagery with contemporary cowboy culture.

Never is it timelier to reflect on cowboy culture than at Stampede time in Calgary:

http://www.calgaryherald.com/p.....story.html

Growing up in central Canada far from the west, cowboys were only an image from the movies. The figure of the strong fearless cowboy living a solitary life on the wide open range becomes the sought after style of Calgary at Stampede time. For one week we all want to be cowboys and don the requisite costume of boots, hat, Wranglers and plaid shirts. We wear this gear to work and after work. Country music is heard everywhere and we crowd into the city’s western bars in hopes of finding “something” – that Wild West spirit where anything is possible. For the rest of the year, we are the “Heart of the New West” , convincing ourselves and the rest of the world that Alberta is so much more than just “cowboy country”.

We secretly and not so secretly love and hate the very image. The dream of the cowboy, reflected in the clothes we don, the music we play, the songs we dance to fills us all with a sense of freedom without modern city life restrictions. It is why we embrace it so whole heartedly. The modern city reappears after the tents are struck, the horses loaded up and taken home, the cowboys return to the ranch. We are all a little freer for living that dream and a little sadder at the sense of loss of what once was…last week and in our prairie past.

Thanks Melinda, for a great article that has made me again ponder these things in the context of my own life and location.

Wow, what a wonderful combination of tribute and analysis about where masculinity, and it’s largest series of visual representations in the cowboy, are today. Possibly because I grew up in Colorado I often forget just how omni-present the imagery of the cowboy/rancher is. From our sports teams like the Broncos, Buffalos, and Outlaws to the image we as a state present to visitors with the bucking horse sculpture that waits outside of DIA images of the idealized west are around those of us who live in Colorado every day. Reading your article made me sit and think about just how frequently we are presented with images of the cowboy and how desperately many (including apparently the image we as a state present to the rest of the world) want to appear “manly.” More than that it also made me think about how divisions within a family can develop. As we have talked about both my brother and I were raised in Boulder and were told by our father to fall into the lines of masculinity, more influenced than I had thought prior to reading your article by the ideal of the cowboy and the west. I am on my way to becoming an academic and will wear sandals and shorts without fail while my brother has been working full time as a rancher for over 5 years. He chews Copenhagen, wears cowboy boots, and is generally what one would visualize a cowboy to be, minus riding a horse out to take care of the cattle since technology moves on even in “traditional” occupations. It is not a surprise that with this being the case my brother is much closer to our father than I am. My apologies for the series of semi-odd associations, but it really got me thinking about a bunch of different things, and I’m sure I could go on (which is always a good sign I think). So I’ll just end with this-awesome article!

Robby Mehls

BAMA Cadidate

Universty of Colorado, Boulder

Tuco (aka the Ugly) shoots a cowboy poised by vengeance envy from the foam of his bubble bath in an abandoned house and says “If you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk.” (The Good, The Bad and The Ugly”, 1966)

My experience of cowboy growing up in France is not as intense as the one from my Dad (probably a generation factor); I do remember watching the show “Lucky Luke” when I was very young. It’s never been a part of my imagination until I was about 18, and my Dad and I did a road trip from Boulder to Thaos, New Mexico. My image of the Cowboy is very rustic, as I see him as being a lone, silent, in touch with his environment, wanderer in the middle of the pampas (with all the dangers it entails), leading his cattle to a safe pasture.

The Cowboy has become commodified symbol, as we can see from generations or from contemporaries in a generation how it has evolved. This is one strong way America “advertises” itself to the rest of the world. Moreover, it is a symbol which has one foot in an old order, and one in a new one; as back in Europe, the farmer’s boys were the one traveling with cattle to nicer fields, though I don’t think they were armed to do so, and they did not have to travel too far, and danger was mild.

Creating a new image out of scratch is a laborious process because it might not be unanimously accepted by an emerging Republic (or Democratic) nation which was built on the ashes of a Monarchy. So giving a little boy 20+ years, a gun, a hat, spurs and leather boots allows him to grow into something new. Especially since America was for the longest time a male dominated country, and women didn’t have the right to play too big of a role. But it is all a big lure, as the social order is not much different.

Disintegrating the known model of the Pater Familias seems to be a path to give space for a multiplicity of voices which has been repressed, like the Women, LGBTs and other minorities.The Bridge Club mentioned this essay shows a shift in the perception that women had of “the leader” as they used to submit, but now actively search to ritualistically burry [the old order?] in order to speak. Through this ritual, women who once revered the bronze statue of the cowboy, and realizing how it has degenerated through the media, romanticization and criticism, or has become outdated (?), have the opportunity to tip the statue from its pedestal.

This outdated model which seems to harm (like “The Rancher”, though I have not seen it so I might be totally wrong), is not due to ill will; it seems to be more a cry for help in this time that is trying to be so different, as the father still builds the fire (No Country for Old Men), and is waiting to be re-accepted, or re-assigned a position to be a part of the family. Or maybe it is the possibility of reverting to the original model of the Father provider, the Forgiving Father, despite the mistakes of its children.

Borrowing a strand of thought from your previous essay “[…] Hidden mothers” and thinking about mothers killing daughters. Mothers encouraging daughters to follow the old order is a form of expressive murder. Daughters realizing the complexity and growing powerlessness of the Cowboy Father can now burry the father so that they won’t have to kill their future daughters.

Cool stuff Melinda, thanks. <3

Dear Melinda,

I find this article intriguing and interesting. I particularly liked the part about the clothes making the man. “The costume is only an image, as much a lie as all the other ways in which we force the movies to serve our dreams of an America that never really existed.” This quote stuck in my brain. It made me think of my father- who past away in 2007 at the age of 55- and one of his favorite films “Mrs. Doubtfire.” Robin Williams character dresses up as an old lady to trick his soon to be ex-wife into letting him take care of their kids. The father gave up his masculinity in order to do something ultimately more important to him- being paternal. He cares more about his family than he does his image. He defies the dominating image of the masculine father who needs to run his house hold and be dominant. My father always wore these shirts that we called “happy shirts.” They had bright colors and fun patterns- mostly like hawaiian shirts. It is hard to deny that the clothes identify a man- but I think its more- the man can choose his image and identity with his clothes. The men who are taught masculinity may be more inclined to dress as a cowboy- a potent image throughout society deemed as “manly”- may loose a key part of their role as a father. A father need not be defined by his qualities or masculinity, but by his love and commitment to his family and being more- being “daddy”. Which is why I believe Robin Williams character in “Mrs. Doubtfire” is an interesting change of pace for film.

Naomi Weingast

Possible BAMA candidate

University of Colorado, Boulder

Melinda,

A beautifully written and compelling piece. Your deconstruction of male iconography is personally moving. Your observations and stunning prose are a testament to human fallibility and the American desire to recreate oneself in the image that you desire. I grew up in Canada, but, as a child I spent many summers in Illinois and West Texas, where I was introduced the literal and figurative image of the cowboy, his masculinity, heroism and stoic virility. In Alpine, Texas when passing the mythical cowboy on the road you would be met with a tip of a cowboy hat, and a hearty “howdy”. I bought a cowboy hat with my father, and my first pair of “Larry Mann” cowboy boots at the ripe old age of 8 – I watched a great many cowboy movies at my father’s side – I was transfixed with the image of the pioneer, the cowboy, the rebel who faced adversity and won – they were the good guys, the lone figure that didn’t quite fit, and never really would. He was who many boys, and a few girls, (I count myself as one) wished to be and some got to be, albeit in their own way – in Big Bend National Park. Thank you for writing such a lovely testament to American culture, and those who have embraced the heart of the cowboy.

Amy G. Barlow

BA, MA, Ph.D. (Student)

University of Toronto (Canada)

This is so good – and needed

It is a breath of fresh air to read thoughts on masculinity through the lens of female artists. The uniqueness of the two artists in the essay is that they’re relationship to masculinity is not one of pitty or ridicule but of its other-worldliness, which is what it indeed feels like to be a man relating to other men. It is its strangeness that holds its uncomfortable power, which is what i respond to in this essay. The strangeness of looking at a masculine image that you are supposed to jump into from day one. I have seen many of the BridgeClub performances and I often find that what seems funny, strange, and beautiful during the performance becomes quite sad days or months later thinking back on it. The performances are so empathetic to the spaces they inhabit that only the strangeness and beauty of what you’re seeing shields you from this soft yet devastating sadness embedded in the performance itself.

I have lived in Texas for a couple of years now and have seen these men and their big trucks, big hats, and broad shoulders. In fact living in a small town in texas is, at moments, quite like an old western, especially later in the evening downtown as people spill out of the bar. These men handle this Image, that Dr. Barlow speaks of, very well and they often intimidate me. They look so tough and cool until you seem them drunk, all of them, drunk in the evening trying to maintain this power while their lips shine with saliva and they hover around their own body. It is intense to say the least.

My father refused to play sports with me (although he was good at them) because he did not want to do to me what his father did to him. However, he did give me cowboy hats and guns and i loved them. I especially loved the rifle cap gun that folded open like a shotgun, but it was the last cowboy hat that he gave me that i begged for as it had red and green feathers in it like truckers had. I had it for a week when he yelled at me to come to the kitchen and look out the window and there it was laying in the rain, feathers ruined. My father is long since gone and my head is so big that i seriously cannot purchase hats in a normal store. While coming back from my wedding my wife and I stopped in New Orleans for a quick honeymoon and I found a black felt hat at a specialty hat store. Its very powerful and i felt taller when i put it on, after i paid for it, it started raining and i put two sacks around it and protected it with my body from the rain. (true story!)

Thanks for this great essay Melinda, so many things to think about.

Matt

Dear Melinda–

I’ve never been a fan of the western–either in film or literary form–and, growing up in the northeast, haven’t taken the time to contemplate cowboy culture (which you’ve thoroughly deconstructed here as having a unitary identity). But! Your writing makes me want to immediately put all of these films in my netflix queue and watch them (or re-watch them, in the case of Midnight Cowboy and Paris, Texas) with a pad and pencil at hand. As a committed close reader, I very much appreciate your ability to parse images from such disparate sources as you do in this piece. I’m particularly intrigued with The Bridge Club and the Rancher. Thank you for opening my eyes (again and again) and helping me see what’s hidden in clear sight!

–Joan

Over the past few days, I have read this article at least a few times. “When Sleepers Wake and Yet Still Dream” is a brilliant article with many layers. The more I read it, the more I uncover. I am primarily fascinated by the representation of men and women through the imagery of clothing. As described, the representation of masculinity had “diminished” in the mid-20th century to early 21st century. By way of the iconography of the Western – a hero/villain is depicted by way of his clothing/accessories. I.E. the protagonist dons a hero’s outfit (sheriff’s badge/outfit), white/brown cowboy hat, etc. or in early silent films such as, Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life – the villain has the iconic twirled mustache. (or in others – the black cowboy hat is symbolic of the villain) I was intrigued to read that issue of masculinity in film, in the time period explored, coincides with (unconscious) feelings and dreams of impotence and the inability to live up to the father’s role (i.e. Avery – antihero). But, with characters such as Hud Bannon or Joe Buck, do they wear the icon/image of the Western hero in an attempt to compensate for their inadequate feelings of masculinity? I think that is possibly what Melinda is getting at here. There is so much more to discuss in the exploration of masculinity in this article, but I must refrain writing an essay as a comment. :)

Through a brilliantly smooth transition from masculinity in film into feminist art, I appreciate how this article questions and challenges paternity by way of The Bridge Club and Sears’ film “The Rancher.” Although the two primary topics in this article contrasts each other (each has their own purpose and drive), I find that one of the many connections between the two lies in the imagery of clothing. The Bridge Club uses day gloves to symbolically break and bury memorabilia. If “women are to “uphold the pillars of the temple with her frail white hand”, then the Bridge Club’s day gloves, used to decimate objects, create a symbolic and ironic statement in contrast to Russo’s remark. By using Russo and The Bridge Club, Melinda makes a wonderfully strong statement for feminist art challenging the “culture of paternal monumentality.”

I know that I have just scratched the surface in analyzing this article, but I look forward to uncovering more layers and understanding this piece more fully. “When Sleepers Wake & Yet Still Dream” gives us a truly captivating insight into the exploration of masculinity in film and feminist art, Melinda’s article opens up the doors for a much need discussion in regards to these two subjects, especially in film.

Thank you Melinda for writing such a great article!

Kelli M Johnson

M.A. Candidate – Cinema Studies

University of Toronto

Melinda,

What a wonderful, haunting article. I especially enjoyed the films you have chosen to highlight the complexity of the cowboy myth and the costume as the real hero (as you nicely illustrate with Joe Buck’s Hud poster). Growing up in Texas you are inundated with this image of masculinity and it is interesting how contemporary female artists are addressing this. From film heroes to politicians to larger than life monuments that live in small towns and airports, we encounter the American cowboy image daily in Texas. My own great-grandfather Pappy lives on in a photographs often looking exactly like Paul Newman’s Hud and the Marlboro man and this article sheds light on what might possibly lie beneath these layers of chaps, lasso and cigarette with two-inch ash…

Thanks for this article and the found photograph of the young boy in cowboy garb was especially moving

Jennifer Dean

Film Editor

Arcade Edit

Dr. Barlow,

I found this to be a thoughtful, efficient, and approachable inquiry into an issue that is both complex and often addressed through facile oversimplifications. Your piece, however, approaches these considerations with a refreshing mix of confidence and restraint. Growing up in Texas, the pressure to perform a certain type of masculinity was always at play. The “cowboy” represents one of the most prolifically “Texan” idol constructions and arguably the first uniquely American. While the Cowboy idol still is prevalent today, I find it beneficial to utilize your argument as a lens through which the many reappropriations of the cowboy-masculine might be examined. John Elway, Keith Richards, and Don Draper each represent manifestations of the manly-construct that continue to prove time and time again that while they certainly wear the costumes of masculinity well, they in fact embody very little beyond their carefully constructed image that is in fact representative of the real—addressing that which is masculine as a popularly decided up on performance rather than an act of personal growth and truth.

A wonderful and enlightening piece!

Sam Carrothers

Director, Little Eden—The Story of Tamina, TX

Although my background is not in film (and absolutely not in westerns), I am always impressed with Melinda’s innate ability to provide such rich descriptions of films that truly bring the screen to life. In this article, what really struck me was the enduring power of these iconic images that cinema has perpetuated over decades. By examining films and even performance art pieces (a la The Bridge Club) that either support or subvert our notions of American masculinity, this article emphasizes the power of visual appearances in relation to the narrative arc of the work.

What can be said without saying? How much of what we see informs what we know? For me, these questions are really about structure—how form and content, seen and felt, internal and external can interact. In this article, we are asked to pay attention to costuming, and Melinda identifies characters whose costumes metaphorically act as skins in some pieces and veneers in others.

A skin is a covering that is different from, but related to the interior of that which is concealed. A skin physically conforms to the musculature and bone structure of the body, offering us some understanding of what lies beneath the surface. Characters whose costuming mirrors their personalities wear skins as visual manifestations of their internal architecture. In my own studio practice as a visual artist, I have always been drawn to skins for their authenticity, but they do run the risk of being boring and predictable.*

Many of the characters mentioned in the article wear clothes as veneers, which challenge our expectations of the individuals who are performing on screen or in person. In woodworking, veneers often deceive us by hiding an undesirable substructure, like an exotic wood veneer on particleboard, but veneers can also be used to invite us to reconsider our preconceptions. In this way, veneers can be a powerful tool for new ways of seeing and thinking, even after the film or performance ends. I really enjoyed reading about Matthew Weedman’s firsthand experiences of The Bridge Club performances because he described their works as being both beautiful and sad. I think that the combination of their very specific clothing and odd, yet ritualistic actions really puzzle the viewer in a powerful way that sticks with them. These veneers are harder to accept, so they linger.

Even still, skins can be shed and veneers can be layered. For example, seeing a president break under pressure offers a moment of vulnerability that shifts the way an audience thinks about the character from one scene to the next. As a maker, I am interested in the decision making process and motivations for utilizing either model for constructing a piece, whether that is a film, performance, or otherwise.

*One artist who I think used skins in a very poetic way, is the late choreographer, Pina Bausch. There is an amazingly poignant documentary by Wim Wenders called ‘Pina’, which I would highly recommend.

Alia Pialtos

MFA Candidate, Ceramics

University of Colorado, Boulder

Great piece Melinda! Recently, I had the pleasure to return to many of the films you discuss in the course of a research project that included an exploration of the appropriation of cowboy garb by counterculturalists in the late 1960s and early 1970s. No doubt, this sartorial phenomenon was inspired by a re-invigoration of the myth of the West as a place that was wild, out-of-bounds, and free from the social hierarchies of the East that attracted hippies far and wide to the Southwest and California. As you so beautifully articulate, the image of the cowboy/Western hero was questioned in Westerns after 1960, and I can’t help but think the broader context of the counterculture played a role here. This wasn’t a space of imagination or creativity equally open to women in the period, and I thank you for the examples of contemporary female artists questioning the authority and monumentality of the Western hero so prominent in visual culture. Besides Calamity Jane in the cable drama Deadwood, does the female anti-hero in the Western exist beyond the figure of the prostitute?

What an honor to have The Bridge Club’s work feature in such complex and considered writing! As a collaborative whose four members grew up in four different regions, we are in the somewhat unique position of being able to address the myths of place simultaneously from an insider’s and an outsider’s perspective: each of our works incorporate both the absurdity that an outsider sees, and the intractability of expectation and legacy felt in one’s own home. Many of the above comments in this thread address the experience of ‘growing up Western;’ to one living outside of the West, the myths propagated through film read as both fantasy and caricature, while (as the above comments demonstrate) within this region, these ideas are innately felt.

Interestingly, in terms of The Bridge Club’s work, the Western male mythos seems to require a female counterpart: the one left behind and waiting. Popular music attests to this relationship, both in the Country genre and otherwise, and this too operates from an ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ perspective on myth: Judy Collins/Suzy Bogguss’ ‘Someday Soon,’ or George Strait’s ‘I Can Still Make Cheyenne,’ respectively, for the (gendered) waiting and leaving; Toby Keith’s ‘Should’ve Been A Cowboy’ for the essentiality of leaving a girl behind; Tom Petty’s ‘Crawlin’ Back to You’ or even Neil Young’s ‘Cortez the Killer’ for mythic stereotypes viewed from outside of the West (cowboys & indians, the sowing of wild colonial oats) and set against the backdrop of a patient Western gal who knows her station in life requires a wait.

Thanks so much for including our work in this compelling (and gorgeous!) piece!

Julie Wills

http://www.juliewills.com

http://www.thebridgeclub.net

Melinda,

Thank you sincerely for this. Immediately upon reading this I thought of Bruce Springsteen’s 1982 album Nebraska. The song “Highway Patrolman” in particular is a favorite of mine from the album. I inspected the lyrics as means of jarring some more thoughts and found two lines in particular which struck me as worthwhile to attempt to conjoin with your piece in this space.

“Maybe you got a kid maybe you got a pretty wife, the only thing that I got’s been botherin’ me my whole life”

This line, about the tortured persistence of a certain psychic something, appears to join arms with the inner battles, lives, and farces described in your article. I began to think geographically about this connection. I imagined these inner battles to be indicative of the landscape of the heartland itself, but also full of contradictions which I did not expect. How is it, that in the geographic moment of this country where the landscape finally flattens out and the sky dilates itself endlessly – where clarity of mind might be most possible – that these tortured male figures you highlight become, even to themselves, the most insular, the most impenetrable? I began to make free associations with ideas of depth, folds in the landscape, burial and then I struck upon your connection with the Bridge Club. The two works you showcase appear to be inversions of each other, one, a sentimental void cut out of the earth, the other, a tearing down of an attempt to sculpturally triumph above it. I found that these polarized movements, up and down, (as well as the psychic and man-made structures we have created which echo them) to relate to the emotional trials and passages of all the characters you represent (I even now think of the oil horse, the forever-bowing stalwart of the American west). If these characters are not monumental in their mythos: Hud’s father and President Johnson, then they are utterly and completely hollowed inside: Hud and Travis Henderson. Is it likely then perhaps, that there lies other, more intriguing and provoking connections between the often empty and arid landscape of the American heartland and the characters it has potently produced over the last century, real and imagined? I leave you with another line from the same Springsteen tune,

“In the wee wee hours your mind gets hazy, radio relay towers lead me to my baby…”

How else does this landscape, in many ways so visually bereft (and yet just full enough) inundate and co-merge with ourselves? Certainly a worthwhile thought for me especially given its connections to Land Art. More to come. Thank you again.

-Alexander Creighton

Professor Barlow,

The ways in which this essay traces a link between the history of American masculinity (or, at least, perceptions of American masculinity) and dreams made me think upon some dream experiences of my own, and what they say about my own perceptions of masculinity. I’ve had a recurring dream, ever since my Father died, in which our final conversation together, from two or three days before he passed, re-plays in a variety of scenarios. What happened in reality is that he told me that he knew he was dying; I already knew this, but hearing him say it made a lot of my latent emotions overflow, and I started openly weeping. Even in his pained state, he knew what to say to make both of us feel better. He asked me to recount my favorite experiences from my life – which really meant, from our life together, as father and son. And as we talked about those experiences, the tears gradually stopped.

In my dreams, the tears don’t stop – the dreams always start in some mundane (or, alternately, surreal) scenario, in which my Dad tells me he is dying. I become emotional, and as he did in life, he stays strong; but it’s harder to stop crying in the dream. It’s he and me doing something that we enjoyed doing together (fishing, going to the movies, etc.) being corrupted by his impending death – and after he talks about, he transforms into the physically weaker, sicker man I knew at the very end. It’s traumatizing. I wake up crying. And in two years, the dreams haven’t stopped.

Your thoughts on masculinity and dreams have given me a new theory about my dreams, though – or, at least, a new way to read them. It never confused me why I was revisiting this moment over and over again – it was our last conversation, and it will always stick in my mind – but perhaps there is more significance to why my subconscious keeps recreating the essentials of that moment. My Dad died at a formative time. It was 12 days after my 20th birthday. I was in the middle of my third semester of college. I had just started living on my own. I had to start being my own man around that time – and it was the time that my primary male role model died. I think it’s common for our basic perceptions of masculinity to be shaped by our fathers, and as I keep striving to make it on my own, my sleeping mind keeps sending me back to the moment my father found strength in death and in grief. I suppose that’s the kind of man I want to be, the kind of strength I want to have in life, and hopefully in death. As with Sheriff Bell, my father’s lighting a way I’m trying to follow, even in death, and it’s through dreams that I am made conscious of this. Conscious of what I consider to be important in my own conceptions of and experiences with this thing we call ‘masculinity.’

There’s a Bruce Springsteen song called “Walk Like a Man,” from his 1987 album Tunnel of Love. The album is about the disintegration of his first marriage, his equivalent of Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, and the first side closes with this song about Springsteen remembering his father, and his childhood, and all these little moments that have turned into formative experiences for him, and how they compel his reading of what it means to ‘Walk like a Man.’ It’s not a song about dreams, but it seems to encompass these same themes – our conceptions of masculinity being shaped over time, by culture and the people we know, until they are deeply sublimated within our subconscious, difficult to suss out without deep introspection.

Thank you for this piece – and moreover, for the chance to reflect.

Jonathan R. Lack

BAMA Candidate

University of Colorado at Boulder