Streaming as Shelving: The Media Past in the Media Future

Derek Kompare / Southern Methodist University

In media studies, we too often regard past media (old films, TV shows, recordings, etc.) without considering how we’re still able to access them. If we pull our focus back, we can better appreciate how our access to past media must always pass through the filters of our present media systems (and often those of times in between), with their particular protocols, practices, and codes. The most salient developments of the present in this regard center on rapidly growing (in terms of volume of data and number of end users) systems of online distribution.

Late April’s flurry of news on the digital distribution front marked revealing signals on the continued transition towards on-demand media system in the US. HBO struck a $500M deal with Amazon for streaming rights to much of its vast library of programming, including The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, and The Wire, and miniseries and original movies like John Adams, Band of Brothers, and Mildred Pierce. AT&T announced that they are developing their own streaming site, and are rumored to be attempting to acquire satellite television distributor Direct TV. Most importantly, FCC chair Tom Wheeler announced that the commission was developing revised net neutrality rules that allow ISPs to create so-called “fast lanes” of service at a premium to content distributors while still ostensibly retaining the openness of the internet to all “legal content.” It’s worth exploring each of these interrelated developments for what they may portend for the future of media distribution.

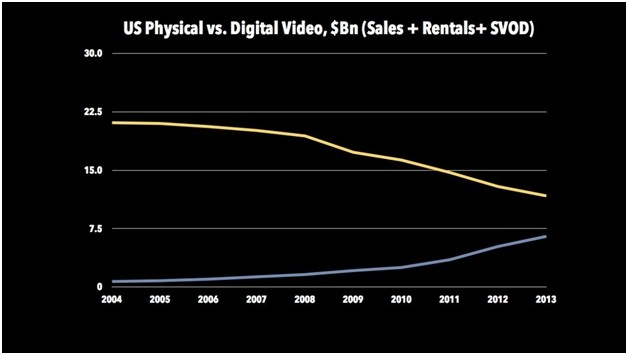

Before that however, one of the overriding concerns of media distributors needs to be acknowledged: the rapidly shrinking consumer market for physical media (i.e., CDs, DVDs, and Blu-Ray discs). CD sales plunged long ago, at the turn of the century, and while it took years for the music industry to figure out online distribution, it seems to have at least worked out a somewhat remunerative system of downloads (through iTunes, Google, Amazon, and hundreds of other apps and sites) and subscription streaming services like Pandora and Spotify. That said, while the latter have exploded in popularity with consumers in the past few years, the margins are thus far not ideal for content owners, artists, and publishers. The revenues regularly reached in the 1990s are not likely to ever return to the industry. As Tim J. Anderson notes, “as digital user environments grow and change every element of the industry will have to negotiate how their productions and contributions are valued and whether or not they may wish to participate.”1 Meanwhile, DVD sales peaked a decade ago, and while Blu-Ray has steadily grown as a proportion of disc sales since that time, the overall trend for the video disc format is firmly down, as shown by this data compiled from Digital Entertainment Group:

This transition is perhaps the major reason for HBO’s decision to finally license a good deal of its library for streaming. The only way to legally access their content to date has been by subscribing to HBO as part of your cable or satellite bundle, or by obtaining them on DVD or Blu-Ray. HBO has long held the line on premium pricing in both areas. They must have realized time had run out on relying exclusively on that strategy, and licensing to Amazon grants them enormous revenue and still keeps the content in wider (or at least, more accessible) circulation to Amazon Prime subscribers. Moreover, it places that content just a couple of clicks away from still purchasing the DVD or Blu-Ray versions, through the very retailer they’ve no doubt already sold many of them already. The move is both a concession to the shifting media market, and a transference of their brand to a new domain. As Myles McNutt remarks, HBO has always eventually, and effectively utilized new forms of distribution to grow their reputation beyond their paying subscribers. Thus, rather than watch Tony Soprano, the Fisher clan, or the denizens of Baltimore fade from memory, they’ve secured virtual shelf space in the next iteration of the cultural archive (albeit still not on Netflix, which remains the de facto arbiter of streaming relevance, as Anne Helen Petersen has observed). Meanwhile, Amazon, while well behind Netflix as a streaming brand, is already solidly the predominant online retailer on the planet. The HBO catalog grants them a bit more legitimacy as they build out their media ecosystem.

AT&T’s actions are more shrouded in secrecy at the moment, but are reactions to the arguably inevitable merger of Comcast and Time Warner Cable. As a telco, AT&T already competes with each of these cable operators in many of its markets. Faced with a new tcomm giant, with unprecedented distribution reach, and, in NBC Universal, a massive content engine, while trying to hold on to their own broadband subscribers (like myself) who’ve forgone their U-Verse TV service in favor of streaming from Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, Crackle, and others, AT&T needs to secure its own future as a major distributor. Yet another new streaming service seems a tall order, but they’ve got tens of millions of broadband subscribers they could easily roll out to, likely at reasonable rates to their consumers. Acquiring Direct TV would hedge their bets, picking up several million new customers, though also generating some conflicts of interest with their TV business (i.e., who would subscribe to both U-Verse TV and Direct TV?).

This brings us to the proposed FCC net neutrality revision, which, at the time of this writing, has still not been released to the public in detail. The gist of the policy adjustment seems to be to allow ISPs what they’ve long sought: the ability to charge content distributors for faster bandwidth. As bandwidth needs escalate with all the HD (and even 4K) video being streamed, this new rule would essentially create a market for acceptable bandwidth. However, in a telecommunications system that’s already much slower, much more expensive, and much less competitive than those in almost every other advanced country, it’s less a robust “free” market than a giveaway to the four big ISPs (Comcast, AT&T, Time Warner, and Verizon) who control over two-thirds of US broadband access.2 Yes, Wheeler assures us that the terms of this transaction must be “commercially reasonable,” but despite his examples of “unreasonable” behavior, that’s exactly the sort of legal phrasing that allows for a vast range of interpretation (not unlike this longstanding policy classic: “the public interest, convenience, and necessity”).3

The new media future will almost certainly see online distribution dominant over physical media, cable/satellite systems, and even venerable over-the-air broadcasting. As the Aereo case (the other crucial media policy development in April 2014) shows, the position of the latter in the emerging media order is far from assured. In the US market, the thick top layer of Netflix, YouTube, Hulu, and Amazon obscures a more diverse and niche-focused array of streamers like Mubi, Crunchyroll, Warner Archive Instant, Acorn, Twitch, and many others.4 While their fortunes currently vary, this week’s developments do not particularly bode well for any of them. If the streams of the present are going to function effectively as the shelves of the future for the texts of the past, we need to take a more active role in media policy.

Image Credits:

1. Six Feet Under

2. Chart, author generated and owned.

Please feel free to comment.

- Tim J. Anderson, Popular Music in a Digital Music Economy (New York: Routledge, 2014), 87. [↩]

- Leichtman Research Group, “2.6 Million Added Broadband from Top Cable and Telephone Companies in 2013,” http://www.leichtmanresearch.com/press/031714release.html [↩]

- Tom Wheeler, “Finding The Best Path Forward To Protect the Open Internet,” Federal Communications Commission, http://www.fcc.gov/blog/finding-best-path-forward-protect-open-internet [↩]

- Europe is also an especially active region for SVOD; see Hannah Goodwin and John Vanderhoef, “Policy and Politics Dictate the Growth of the European SVOD Market,” Media Industries Project, April 21, 2014, http://www.carseywolf.ucsb.edu/mip/article/policy-and-politics-dictate-growth-european-svod-market [↩]