Reflections on Actors: Minority Identity Actors in the Creative Industries of Contemporary Britain

Simone Knox / University of Reading

With a keen interest in the lived experience of contemporary screen culture, I wish to follow up on my previous reflections on the casting of British actors in US film and television, with a look at the working environment and conditions of professional actors in Britain. To sketch out some of the broad contours, I have already noted that in Britain, firstly, the competition for roles has increased since the British actor union Equity was forced to discontinue as a closed shop in the 1990s. Secondly, with the decline of repertory theatre, the perennial issues with the British film industry and its fragile infrastructure, as well as developments within television (including lack of available funds, the rise of light entertainment/(scripted) reality formats), the number of available dramatic projects has decreased decisively. Thus, there is fiercer and fiercer competition for scarcer and scarcer roles, in a home market that is already and inevitably limited due to its overall size. This has only helped to make acting a profession increasingly and significantly marked by a lack of stability and security.

This is undoubtedly a difficult challenge for anyone working as a professional actor in contemporary Britain, but what has emerged from the actor’s perspective is an additional issue, namely that the casting of actors across the borders of ethnicity, race, class, region and/or disability is rare. Let me here flag up that, although it is far from unproblematic, the concept of race “continues to play a fundamental role in structuring and representing the social world.”1 Intending to “understand race as an unstable and ‘decentered’ complex of social meaning constantly being transformed by political struggle,”2 my interest lies precisely in the ways in which (including assumed) notions of difference work or are made to work within the creative industries. Recent years have seen high-profile criticism from within the acting profession for a lack of color-blind casting in Britain

This has been perhaps most forcefully expressed by actor David Harewood, who has spoken of a failure to take risks with black casting in Britain, which he claims led him to seek work in the USA, where he was cast as the Deputy Director of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center for Showtime drama Homeland: “I knew what I needed to do. I simply wouldn’t have been given a role of that strength and authority in the UK.”3 He has further said: “It’s taken me 26 years and a couple of trips to America to convince people in the UK that I can carry a show and that I can be a leading man.”4 Here, Harewood echoes some of the frustrations also articulated by Marianne Jean-Baptiste, who, following her experience of being excluded from a group of British actors invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1997, went on to find success in the USA, where she has starred in CBS police procedural Without a Trace.

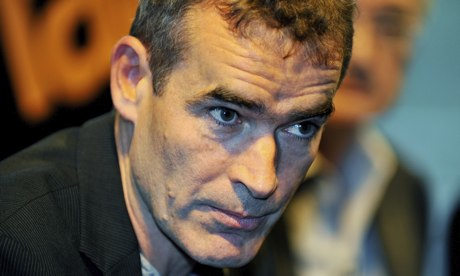

Lest anyone should think that these may be the unrepresentative grumblings of a frustrated few, such criticism of British culture has not been limited to British actors – indeed, neither British, nor actors: US actor Morgan Freeman has criticised the British film industry for not giving enough opportunities to young black actors, while Rufus Norris, the National Theatre’s incoming artistic director, has commented that:

I think it’s fantastic that those shows [high-profile theatre productions featuring all-black companies] are happening and that is a small part of the thing that David [Harewood] and other black actors talk about, but the real issue is that if you look at American TV drama and theatre, there is much more colour-blind casting […] We are very much behind America in that sense and I think what Marianne [Jean-Baptiste] was talking about when she left Britain to go and live in LA a long time ago, is still very true. It’s the way we cast black actors.5

It is worth pointing out that the commentary cited above stems from established creative individuals who have evidently felt able to voice their concerns. This criticism is more than likely shared, if not felt more acutely, by less established actors, who after all constitute the vast majority of the acting sector. It certainly points to wider on-going issues of a lack of strong black roles and presence of stereotypes in contemporary British culture, which deserve attention that I cannot give them here.6

However, what I wish to give attention to now is that a similar problem concerning a narrow approach to casting has also been noted by a different group of minority identity actors in Britain, namely British East Asian actors. Following several controversial casting decisions, including the 2009 staging at London’s Arcola Theatre of More Light, which featured no East Asian performers despite being set in China, and the RSC’s 2012 staging of The Orphan of Zhao with a predominately white cast, recent years have seen public criticism from British East Asian actors about the unequal playing field for performers and lacking proper implementation of color-blind casting, concerned to challenge the habitual silence marking their communities.

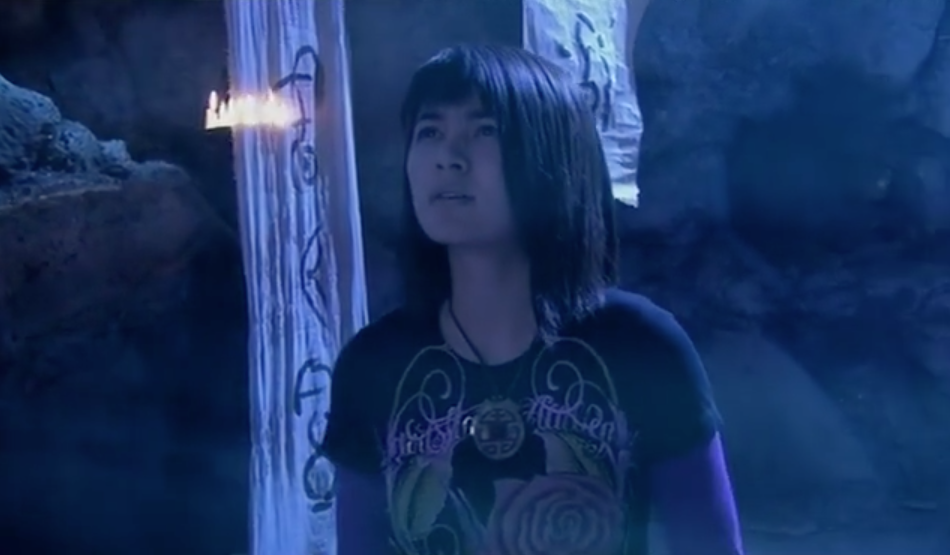

British-Chinese actor Jessica Henwick has noted her personal experience of more audition opportunities being available for white actors, and evoked comparative references to the USA, echoing those by Harewood et al., with her view that: “In British TV, if there is an Asian character there usually has to be a reason for them to be Asian, whereas in America you have a lot more roles where the person just happens to be Asian […].”7 Andy Cheung has identified a lack of equality of opportunity as follows:

Putting it bluntly, it seems to be that white actors can play anything and to a lesser extent British blacks and British South Asians, but not East Asians […]. I get the feeling that stage directors are not confident in British East Asian actors being on stage in anything other than East Asian stories. As a British Chinese actor, I feel like a black man living in the fifties.8

Daniel York, co-founder of the British East Asian Artists organization, has argued for a self-perpetuating lack of confidence bearing down on British East Asian performers:

The whole industry is kind of reluctant to cast east Asians in non-race specific roles. We are generally only thought of as the Chinese takeaway man or the Japanese businessman. It’s incredibly hard for an east Asian person to build up the track record that would enable the RSC to feel confident in casting them in a decent role. We’re not on the radar because we’re not working very much.9

Meanwhile, writer and performer Anna Chen has added further detail to the debate: “I write my own stuff because I realised ages ago that parts are not written for Chinese actresses and colour-blind casting is all well and good, but it is one-way traffic.”10

These impressions and personal experiences tally with my own on-going, quantitative and qualitative research on the presence of British-Chinese actors in British television, in that what emerges is an account dominated by role segregation and stratification. Drawing on the seminal work by Eugene Wong,11 it seems still the case that, if a role is not specifically written for a minority identity character, it is more likely to be cast with a white actor; white actors can portray minority identities, but not vice versa; and the larger a role, the more likely it is that a white actor will be cast. With reductive representations still to be found in acclaimed contemporary British television drama, I am mindful of Karen Shimakawa’s point that

Asian American performers never walk onto an empty stage; […] that space is always already densely populated with phantasms of orientalness through and against which an Asian American performer must struggle to be seen.12

This not only also applies to British East Asian performers, but crucially must also pertain to the point of audition. It is already at the casting stage that much, and significant, struggle plays out, unwitnessed by the eventual spectator. This matters not only because of the resulting representational impact on the creative (screen or stage) product, but also because of the impact on the professional sector. Here, it is important to not forget that, faced with often limited roles on offer, actors, and especially less well-established ones, are people in need of making a living.

To conclude, more needs to be said about further identity groups, and the ways in which ethnicity/race/gender/class/et cetera lines intersect. The actors’ views cited above deserve further critical interrogation; for example, to what extent do these impressions by British actors of the USA – a screen culture long associated with reductive representations and tokenism – match the experiences by their North American peers? Certainly, from actors’ discourse, striking parallels and overlaps emerge between the two groups I have focused on. Further research is needed into the socio-cultural parameters, commercial pressures and cultures of production – or rather, pre-production – in which creative production personnel in Britain currently operate. Here, the unequal treatment and discrimination minority identity actors in Britain have experienced point to the absence of diversity within production sector roles, and especially diversity paired with commitment to change. That high-profile professional criticisms have been made is to be welcomed, just as it is to be hoped that the different professional groups can come closer together over their common challenges, and join up with academic research, to collectively push for increased cultural representation and participation, and animate public debate, in the still early days of the twenty-first century.

Image Credits:

1.David Harewood in Homeland (Showtime 2011-present). Author’s screenshot.

2. Jessica Henwick in Spirit Warriors (CBBC 2010). Author’s screenshot.

3. Marianne Jean-Baptiste in Without a Trace (CBS 2002-2009). Author’s screenshot.

4. Theatre director Rufus Norris.

5. More Light, Arcola Theatre, London (2009).

6. Daniel York on the cover of Equity magazine (Spring 2011).

Please feel free to comment.

- Omi, Michael and Winant, Howard. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. Second edition. New York: Routledge, 1994, 55. [↩]

- Michael and Winant 55. [↩]

- http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/feb/05/black-british-actors-america [↩]

- http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/homeland-star-david-harewood-bemoans-lack-of-black-roles-in-uk-7966293.html [↩]

- http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2013/jun/13/black-actors-casting-uk-us-rufus-norris [↩]

- See, for example, Bourne, Stephen. Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television. 2nd edition. London: Continuum, 2001; and Malik, Sarita. Representing Black Britain: Black and Asian Images on Television. London: Sage, 2002. [↩]

- http://www.newstatesman.com/2013/10/where-exactly-are-my-british-chinese-role-models [↩]

- http://www.thestage.co.uk/news/2009/06/british-east-asian-artists-lambast-racist-british-theatre-for-lack-of-acting-roles/ [↩]

- http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2012/oct/19/royal-shakespeare-company-asian-actors [↩]

- http://www.thestage.co.uk/news/2009/06/british-east-asian-artists-lambast-racist-british-theatre-for-lack-of-acting-roles/ [↩]

- Wong, Eugene. On Visual Media Racism: Asians in the American Motion Pictures. New York: Arno Press, 1978. [↩]

- Shimakawa, Karen. National Abjection: The Asian American Body Onstage. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002, 17. [↩]

Pingback: Reflections on Actors III: The Work of the Dubbing Actor – Performing Gollum in the German version of Lord of the Rings Simone Knox / University of Reading | Flow