Kell on Earth: Kelly Cutrone And The Rare Failure Of Brand Bravo

Jorie Lagerwey / University College Dublin

If any American cable network has mastered the art of creating a “lovemark,” it’s Bravo1 . Bravo’s trademark blend of wealthy, catty women, the knowing “Bravo wink,”2 bright colors, and urban locations is a perfect fit for the audience it’s dubbed the “affluencers” who respond to Bravo’s “passion points” of food, fashion, beauty, design, digital and pop culture3 . The ideological baggage that comes with the Bravo brand is a complex celebration of female economic power and entrepreneurialism, combined with an ironic vision of the successful women who embody those qualities as out of touch at best, and just plain crazy at worst. The women on Bravo’s most popular series too often find themselves cornered into one of the network’s most persistent representational strategies; though acknowledged as “working women,” Bravo tends to obscure the labor that goes into these women’s businesses in favor of highlighting the personal labor they devote to the creation of “self-as-brand.” I’ve dubbed this representational sleight of hand the “Working on Me Tendency,” and while it might be troubling, it works brilliantly.

Except on the extremely rare occasions when it doesn’t. Researching an ongoing project about Bravo and its women, I encountered a Bravo show I hadn’t heard of, Kell on Earth, which aired for a single 10-episode season in 2010. I quickly realized that this show, which ticks so many of the boxes on Bravo’s brand strategy checklist, ultimately fails not because it doesn’t have compelling characters, fast pacing, and the right amount of character friction, but because where the typical Bravo show sleekly naturalizes the “Working on Me Tendency,” both the content and the aesthetic of Kell on Earth highlight it as an ideological fiction spun by brand Bravo.

Kell on Earth follows female entrepreneur Kelly Cutrone, founder of People’s Revolution, a bi-coastal fashion PR firm; believer in syncretic new age spirituality; and self-professed “Power Girl” and “Momma Wolf.” Bravo, though founded in 1980 as a television home for the performing arts and a decidedly high-culture take on film, including its flagship show Inside the Actor’s Studio (1994 – Present), morphed over the years into a reality TV powerhouse and one of the most lucrative non-sports channels on American cable television. NBCUniversal, who bought Bravo in 2002, promotes the company this way:

“Bravo Media continues to translate buzz into reality with new and inventive original programming that tap into the network’s “passion groups” of Food, Fashion, Beauty, Design and Pop Culture. Delivering more breakout stars and ratings juggernauts to the most engaged, upscale and educated audience in cable the network earned its sixth consecutive record-breaking year in 2011 and scored its best year ever across all key demos in primetime and total day, digital platforms and financial metrics.”

Cutrone’s fashion-centric business, captured at its most chaotic in the weeks leading up to and during Fashion Weeks in New York, LA, and London, hits three of its network’s five “passion groups” with fashion, beauty and pop culture, and shot in 2010, shows Cutrone and People’s Revolution tapping into the digital culture passion point while learning to navigate (for them) new waters of transmedia marketing. Kell repeats Bravo’s formula, seen on The Rachel Zoe Proejct (2008 – Present), Pregnant in Heels (2011-2012), and the ongoing post-Housewives Bethenny Frankel franchise, of following female entrepreneurs about their work and family lives. Cutrone’s house, a So-Ho brownstone with living spaces on the 4th floor and the People’s Revolution offices below, allows her to spend time with 7-year-old daughter Ava without sacrificing her extraordinarily long working hours. More importantly for Bravo, it condenses the work/life space into a single location, both making its patented blend of home and work life more convenient for production, and potentially highlighting the ease of constructing the work/life balance so important to postfeminist subjecthood.

But simply looking at a publicity still from Kell compared to the Housewives of the same city, we can see that Cutrone’s look, and that of the show, doesn’t quite fit.

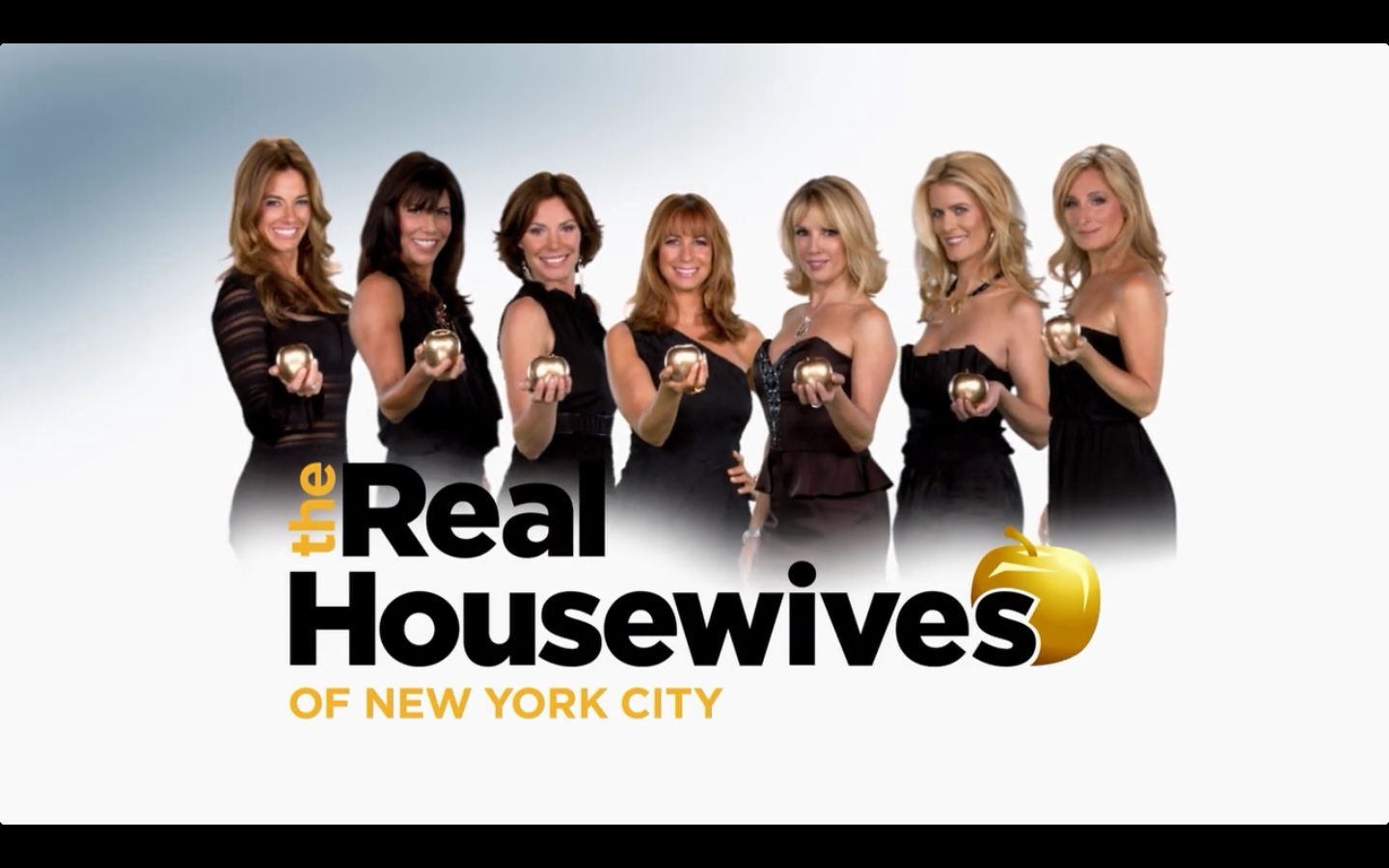

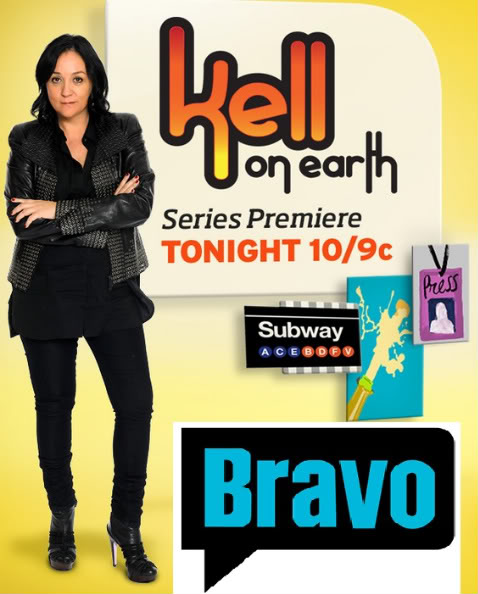

Compare the Publicity for the Real Housewives of New York4 with that of Kell on Earth

The Housewives are smiling, in evening gowns, against a white background; the gold accents set off the black and cultivate an image of simple elegance, even poise. Cutrone slouches, in casual clothes, amidst dark colors. The fiery font, meant to call our attention to the word play in the title, droops like Cutrone’s expression. The whole image is kind of depressing, in contrast to the peppy, smiling, heavily blow-dryed and made-up performers on the rest of Bravo’s shows. Even inserted into the yellow promo image Bravo uses for all its bugs and on-air spots, Cutrone is more goth than glam.

Kell is more goth than glam.

The show itself is shot primarily in Cutrone’s office, which is messy, crowded, and almost entirely black and white. In contrast, the Bravo brand features sun-kissed, saturated color and domestic and leisure spaces. The emphasis on geography of urban centers, of luxury tourism, and notably, of sunshine in LA, Atlanta, Orange County, the Hamptons, and Manhattan in the summer, is absent from Cutrone’s 20-hour work day existence. The low-rent aesthetic of both the office décor and the shooting style, in comparison to the rest of Bravo’s reality stable, reveals fashion and branding to be work. In contrast, the labor that goes into brands like Bethenny Frankel’s Skinnygirl are narratively elided in favor of lunches and social events. In terms of character, the self-as-brand nature of Frankel and other Bravo stars’ endeavors means that there is a constant performance of self, a calculated discipline over bodies, dress, weight, make-up, and relationships.

Cutrone, in contrast, is in the business of promoting other people, making self-promotion and self-branding explicitly forbidden. Any People’s Revolution employee working an outside event must wear all black, the better to fade into the background not to draw attention away from the real commodity, the clothes and the personalities there to wear, advertise, and purchase the fashion. In other words, Cutrone’s business, seemingly perfect for the self-as-commodity, female- and fashion-centric Bravo brand commits the Cardinal sin of pointing out ways in which self-branding is sometimes detrimental to the actual business. This rejection of the self-as-brand flies in the face not just of Bravo’s brand and the work of so many of its Bravolebrities, but also calls attention to the very disjunctures between feminist and postfeminist achievement that Bravo seeks to hide.

For example, while running a profitable business might be labeled a feminist achievement, being a doting mother might characterize postfeminist success. One of Bravo’s brand images is that of postfeminist luxury motherhood, but while Cutrone’s nanny is not featured, she is not hidden, and Cutrone’s constant worry about her limited time with Ava calls attention to the impossibility of accomplishing both the affective labor of motherhood and the economic labor of owning a business with the casual ease and implied lack of paid help seen so often on other shows. Cutrone’s mothering is actively displaced onto her staff as she talks about “raising” rather than training her employees, fixes them up on dates, and frequently refers to herself as their mother figure; her first book, which she was writing during filming, is called If You Have to Cry, Go Outside: And Other Things Your Mother Never Told You. This displacement of affect from biological daughter to employees and further to the book-buying public, again points to the tension and contradiction implicit in Bravo’s brand. The impossibility of containing these contradictions is further evidenced in Cutrone’s near constant discussion of the economic recession and the ways in which it is threatening her business5 .

For its brief ten episodes, Kell on Earth illustrated the ideological contradictions of Bravo’s style of luxury postfeminism. On one level, a woman who openly says she doesn’t fit in, doesn’t wear make-up and never buys the clothes she promotes obviously isn’t a suitable brand ambassador for a company like Bravo that is built on selling mass market luxury and benefitting directly from advertising dollars paid by cosmetics and clothing companies. But Cutrone’s very failure in this regard highlights links between corporate profit and branding – links that an affect-based brand economy must disavow in order to function. Kell on Earth’s so-called failure begins a compelling conversation about the rigid boundaries of postfeminist discourse and the ideologically polished veneers of “quality” reality television.

Image Credits:

1. Full Cast Photo

2. Kell on Earth

3. The Real Housewives of New York

4. Kell Advertisement

Please feel free to comment.

- Back in 2004, Henry Jenkins described a then-emerging affective television economy, including the cultivation of so-called ‘lovemarks.’ Henry Jenkins, “Affective Economics 101,” Flow TV 1.01, September 20, 2004. Accessed June 13, 2013. http://flowjournal.org/2004/09/affective-economics-101/ [↩]

- Emma Rosenblum, “The Natural: How Andy Cohen Became Bravo’s Face,” New York Magazine, January 8, 2010. Accessed May 29, 2013. http://nymag.com/arts/tv/features/63010/ [↩]

- Bravo’s ad sales website lays out its brand profile and its audience’s “passion points.” http://www.affluencers.com/ Accessed May 29, 2013. [↩]

- Screen grab from the credits of Real Housewives of New York City Season 2. Bravo, Spring 2010. Netflix. [↩]

- Other Bravo shows have acknowledged the toll the economic crisis of recent years has taken on castmembers, but writing about the Orange County cast, Vicki Mayer points out that it is often framed as an opportunity to consume. Vicki Mayer, “Housewives in Crisis, Economic That Is.” Antenna: Responses to Media and Culture, January 23, 2010. http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2010/01/23/housewives-in-crisis-economic-that-is/ Alternatively, it is framed as a chance to rebrand, as Sonja Morgan attempts to do on seasons 4 and 5 in New York. [↩]

Pingback: Bodies and Bravo’s Brand on The Real Housewives of Atlanta and New York Jorie Lagerwey / University College Dublin | Flow

What a great article, and a wonderful style of writing. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your analysis of Cutrone’s (very authentic) character and how she is a misfit for the Bravo brand strategy. I think this show could have gone on for a few more seasons, given that the fashion industry never sleeps and there is always exciting material to film. But, just as you pointed out, it doesn’t fit this particular channel and Cutrone’s personality showes too much truth about being a woman who works, has a child and has an opinion. I wonder if it is an American thing aswell? Reality TV-shows in Europe seem to be less groomed and prefer to show more rough momets (i.e. Hell’s Kitchen…