Space Ghosts: Cartoons and Talk Shows

J.D. Connor / Yale University

It’s often only at the end of something that you really know what you’ve been up to. This column has been like that. Getting ready for this last iteration, I realized that the first two installments, “Aspect Jumping” and “Parkives” took up the historical sedimentations of technology and reception within structured experiences. The first looked at shifts in aspect ratios in film and television; the second read theme parks as agglomerations of relatively durable regimes of technology, narrative, and contract. This one is about cartoons and talk shows, or hybrid dimensional interaction in the behaviorally quantized space of the near-now.

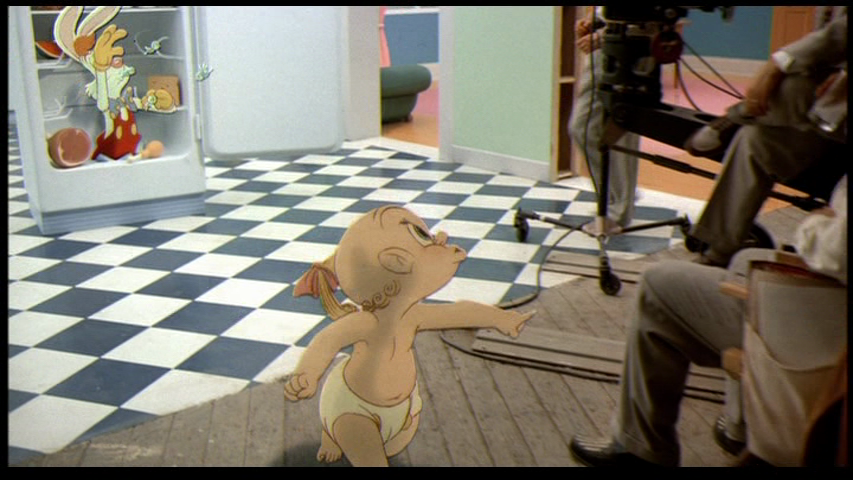

Realtime or pseudo-realtime cartoon/human interactions rely on temporal expectations generated by extensive familiarity with the production requirements of animation rather than the unique dimensional difference between cartoons and humans. The older charms of the “Out of the Inkwell” (Fleischer, 1918–29) series for example, depended on the unexpected “liveness” of the inanimate, often combining liveness with the impossible propagation of various forces across the animated/live-action barrier. In general, when the animated character is turned loose in a live-action world, we might call that a transdimensional incarnation. In contrast, when the animated world is revealed to be continuous with our live-action world—as when Roger Rabbit (Zemeckis, 1987) walks off a set we didn’t know was a set—we might call that a dimensional jointure.

In contrast to these, there are two general forms for the contemporary hybrid scene, they are as much temporal as spatial, and they are converging. One relies on the exponential increases in rendering power to produce a realtime manipulable CGI puppet. In these instances (typified by Motus Digital, motusdigital.com), the interaction is near-live, the intelligence engine for the responses is human, but the visual is animated. The realtime Zombie is not all that different than Craig Ferguson’s robotic sidekick Geoff or the Wizard of Oz. The touchstone for the social significance of the puppet-hybrid is Max Headroom.

Max was a late–80s transmedia star of fiction, talk, and commercials. Ostensibly CGI, he was actually an actor, Matt Frewer, in makeup in front of a cell-animated loop. An avatar from “twenty minutes into the future,” Max was so cutting-edge he was glitchy—his image locked up and he stuttered. The politics of Max were typically 80s in their incoherence. His narrative television series played cyberpunkishly at épater les networks when his human counterpart inveighed against “blipverts” and the subordination of politics to entertainment. His talk show appearances as either guest or host turned that sub version toward self-referential humor and the tech drifted into the background in favor of easy jokes about the price of fame, or homeless windshield washers, or Trekkies. And his pitchman-self shilled for New Coke after the reintroduction of “Coca-Cola Classic.” It didn’t particularly work, any of it. Still, you could see where the callow techno-futurism was leading.

The underlying configuration has lived on. The pseudo-CGI animated puppet was the vehicle through which the popular understanding of the structure and operation of the media-entertainment complex could be incorporated into an experience of contingent simultaneity. It wasn’t just meta-, it was meta- and ordinary; and our recognition of the imbalanced twinship of reflection and expression found its emblem in Max’s faux stutter.

More interesting than the puppet is the repertoire-based animated automaton. Here, liveness goes hand in hand with a restriction on what can and can’t be pulled from a library of actions. Space Ghost: Coast to Coast (1994–2004) is the paradigm, and it remains decisive. SGC2C began at Cartoon Network as part of Turner Broadcasting’s attempt to monetize the library of Hanna-Barbera cartoons it purchased in 1991. The H-B shows exemplified the studio’s limited animation style, regularly relying on duplicate backgrounds or action sequences and long sections of standing-around-talking.

For Coast to Coast, creators clipped and rotoscoped elements from the 1960s originals, reassembling them into a talkshow format. Space Ghost hosted, Zorak (a mantid) served as bandleader, and Moltar (a lava-man) served as producer/director. Even the interviews were subjected to the same process of breakdown and rearrangement. Whatever the Q&A might have been when the guest taped it, by the time it aired, only slivers of the original remained, now sandwiched between dada-esque flights of ghostly irrelevance (“Do you like croutons?”), cutting remarks, and the ultra-dysfunctional byplay between Space Ghost, Zorak, and Moltar.

At every level, then, Space Ghost Coast to Coast was about repertoire and rearrangement: the original cartoons, the strictures of the talkshow format, the sliced-and-diced interviews. Under intense corporate pressure, nonlinear editing tools revealed the pre-scripted strings of behavior in the old cartoons and discovered that nonlinearity in the behavior of talkshow guests and capitalists intent on maximizing return on investment. The “on-the-cheap” aesthetic of the original was thematized and became the emblem of Cartoon Network’s own awkward synergistic aims.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vWp5JWLYgg[/youtube]

How much independence could be wrought from such constraints? Moltar was given the CGI treatment and repurposed as the host of Toonami, an anthology show. But even when budgets were more forgiving, repertoire within animation remained an essential problem. Youtube abounds in clips showing Disney reusing whole sequences of gags. At DreamWorks, the crowd scenes in Prince of Egypt relied on a CGI puppet technology with a new logic engine that strung together a library of actions to produce sufficient variation that it would usually pass unseen.

By the turn of the millennium it was clear that, given a big enough budget and sufficient rendering capacity, the repertoire and the puppet might be effaced. When could something similar be achieved live?#

The current-events comedy cartoons produced by Next Media Animation give the “Taiwanese animation treatment” to American headlines. Part of their effectiveness (which seems to have waned) lies in the way they underline the international labor imbalances that make offshoring necessary for animation. By keeping their Mandarin voiceovers and their Taiwanese virtual hosts Jen-Jen and Vanessa, the clips turn the question “Why do I care about Lindsay Lohan’s legal troubles?” into the more critical “Why would a Taiwanese animator care about Lindsay Lohan’s legal troubles?” The critical edge of the second question is not simply cultural but economic: why should my interest in Lohan become a source of labor pressure on someone half a world away?

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGizpnRf-FQ[/youtube]

Part of what excuses our interest in those cartoons is the intuition that the labor necessary to make them has shifted away from the ink-and-paint slavery the Simpsons satirized toward the less exploitative, more improvisatory writers room. When Ted (the R-rated teddy bear) appeared on Jimmy Kimmel, Seth Macfarlane did the voice interaction in a MoCap suit. Tippett Studio combined that data with keyframed versions of Ted walking on stage for the final segment. The labor crush for this, and for Ted’s appearance at the Oscars, was intense.

Web reactions to Ted’s “live” appearances concentrate on the realism of the event—his reflections in the shiny floor, his fur, his movement in the chair. Max Headroom’s glitchiness is disappearing, but the wow-factor still relies on our implicit knowledge of the labor and technology brought to bear on the bear.

Less impressive as animation, but more striking for its instantaneity, is the online animation software XtraNormal. Here, “if you can write, you can make films,” by pulling from a library of sets and characters, actions and voices. Half the fun of the resulting shorts comes from the synthesized voice’s seemingly constant sarcasm, a built-in world-weariness that makes the cartoons the perfect vehicle for expressing your ennui. Several popular XtraNormal cartoons detail the tribulations of academic life and the futility of the intellectual labor while others cover the ironies of contemporary politics. In these cases, the transdimensional incarnation has inverted. It’s our own behavior that is quantized; our own labor that is machine-replicable; our own dependence on generations of capitalism’s creative destruction that we recognize here, again and again, live.

Image Credits:

1. Dimensional jointure in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. Screen capture from author.

Please feel free to comment.

Craig Ferguson mentioned to John Waters as well as Kelsey Grammer during “The Late Late Show” interviews that he was interviews on Space Coast Coast to Coast. However, no one seems to be able to find that episode or his interview. Jon Stewart and Conan O’Brien were interviewed as well, and that is documented in episode guides, but where is the Craig Ferguson episode? Please let us know what occurred; Thank you!