Habit-Change in the Mobile Present II: Ghosts of the Horseshoe and Remembering History Otherwise

Heidi Rae Cooley/ University of South Carolina

In my last column, I introduced a theoretical framework for thinking about how GPS- and WiFi-enabled mobile devices with Augmented Reality (AR) functionality might elicit habit- change. I cited American pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce. I explained that for Peirce habit-change materializes as a kind of “mediated immediacy” or intellectual sympathy. A process of cognition, or meaning-making, it transpires on the cusp consciousness before we know that we know. Meaning-making binds together a community of interpreters so that they can communicate with one another. Moreover, according to Peirce, meaning-making is always conditional: If certain conditions pertain, then a particular meaning is likely to result. Because cognition is both social and conditional, it is never necessarily certain. It “works” through habitual repetition and change is always possible. I locate AR’s potential to change habit in the moment when a physical place might be experienced and understood in terms other than those that are conventionally reinforced. Such potential runs counter, perhaps, to consumer-oriented AR applications, such as Layar, Junaio, and Vicinity, that work to reinforce rather than alter habit when they identify place with consumerism. To develop a counter example, I will describe a project in which I am currently involved that uses AR to re-imagine a University campus.

South Carolina College (1801-1865): USC’s Historic Horseshoe

The University of South Carolina is the site of one of the most intact “landscapes of slavery” in the United States.1 Situated at the heart of the modern campus, the historic Horseshoe is what remains of the original South Carolina College (1801-1865). However, the students, faculty, administrators, and visitors, who traverse these grounds today are for the most part unaware of its complex history. No plaques on site or guides describing the grounds indicate that remnants of the antebellum campus stand because of the labor of enslaved persons: The hands of enslaved labor attended and served the students and faculty of South Carolina College. The hands of enslaved labor cared for and maintained the campus. The hands of enslaved labor molded, hauled, and laid the bricks that are the foundation of the site. Physically imprinted on the bricks of the buildings that still occupy the grounds and the Wall that encloses the site are evidence of the fact of these hands having-been.2 People habitually walk the brick paths that criss-cross Carolina’s historic Horseshoe without realizing that they tread on a landscape built and maintained by people who had no choice. If they consider its history at all, they are likely to appreciate the fact that “the entire student body volunteered for Confederate service”–a story reinforced by campus tours and by a commemorative plaque that stands at the entrance to the Horseshoe grounds.

Ghosts of the Horseshoe3

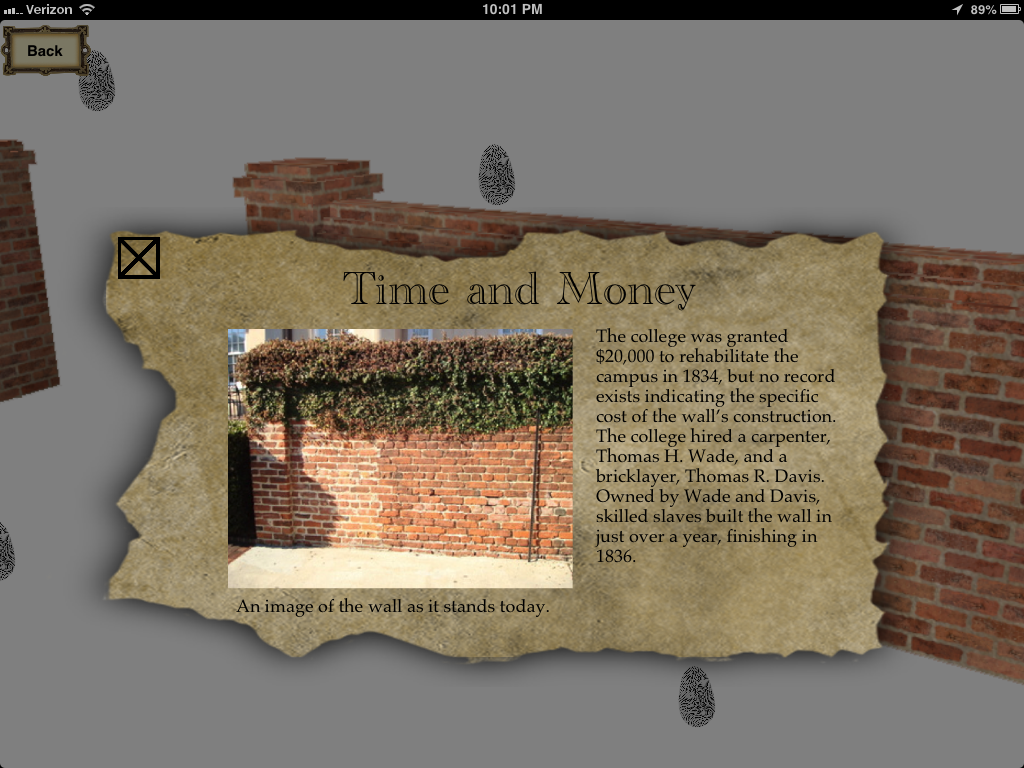

Ghosts of the Horseshoe (Ghosts) aims to alter habitual traversals of the historic Horseshoe by means of a mobile interactive application running, in the first versions, on iPhones and iPads. It deploys game mechanics, as well as Augmented Reality (AR) and GPS functionality, in order to generate awareness of and questioning about this historic grassy space at the center of a university campus. It organizes content into three distinct but overlapping themes: architectural ghosts (e.g., extant but altered buildings and razed slave quarters); human ghosts (e.g., faculty, students, and un/named enslaved persons); and the Wall. Content pertaining to these three threads is called-up according to three separate time periods, as defined by the Wall’s: inception (1801-1835); construction (1835-1836); and existence as the perimeter of SCC (1836-1865).

As participants walk the grounds with a GPS- and WiFi-enabled iPad or iPhone, they receive invitations to interact with content points pertinent to their location. Sometimes content points open onto AR layers, that allow participants to see historical figures, photographs, or 3D models of buildings while looking “through” the screen at the real-time camera image of the Horseshoe. Sometimes content is delivered through audio–historically-informed voice re- enactments and/or period appropriate music and ambient sounds (e.g., the clatter of dishes, the rumble of carriages, the gravelly sound of brick-laying). All the while, the application tracks participants’ engagements and traversals, and offers them opportunities to review where they have gone, what they have experienced, and what they might yet encounter. Likewise, participants are able to submit comments to a community website where they can review others’ comments and explore ancillary materials.

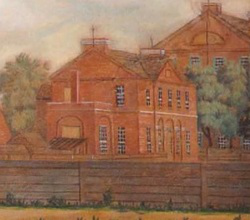

Ultimately, Ghosts seeks to intervene in a typical misconception about history: namely, that all pasts are equally available for reconstruction. Validating this point is the fact that no photographic imagery of enslaved persons exists (as far as we know), and only one painted representation of a “black man at South Carolina College” appears in a ca. 1820 landscape painting. While portraits of the faculty exist, and even hang on the walls of buildings on campus, and while we can surmise what an average student matriculating at South Carolina College looked like based on the economic, social, and/or political status of the families who sent their sons to SCC, we know virtually nothing about the enslaved persons who ensured the day-to-day functioning of the College.

We do have ledgers providing accounts of the “hire” and purchase of enslaved persons. We also have faculty papers and letters that address matters concerning “hired” servants. But these artifacts only provide for a representation of campus life according to a white enfranchised perspective. In contrast, Ghosts turns to what we do know remains of them: the impressions left by hands on the bricks that comprise the built environment of the Horseshoe and the Wall that surrounds it. Ghosts uses thumbprint imagery and digitally-rendered thumb impressions to represent the enslaved persons who labored at SCC from 1801 through 1865. Touching a thumbprint or thumb impression delivers to the screen specific details about daily life of enslaved persons. It is by means of the gesture of touch that Ghosts hopes to elicit critical awareness and empathic response to the complex history of USC’s historic Horseshoe.

Inhabiting the Horseshoe Otherwise

No one is surprised to discover that slavery existed in South Carolina. The cognitive difference the app aims to introduce has to do with understanding the abiding affect of this “peculiar institution” on the landscape of the present University. The University’s prevailing self- representations actively work to minimize awareness of slavery’s survival. For example, the official website refers to the institution’s “colorful history” and points to the Horseshoe’s historic buildings as offering a “fascinating story” that epitomizes the enduring qualities exhibited by the “Outstanding statesmen, scholars, scientists, administrator, and business leaders” who resided, studied, and/or taught there.4 Ghosts of the Horseshoe troubles such readily digestible representations. It draws participants into relation with history and historical figures by turning the mobile micro screen into a “window” onto the past, one whose real-time image responds to touch, gesture, and location. Ghosts uses the power of the digital experience to “fill in the gaps” where institutional history and habitual thinking fall short. Not just the digital but more specifically, the mobile and, therefore, embodied experience facilitates a deeper empathy with the past. It is not just that one imagines the work of slaves forming, firing, and carrying bricks and, subsequently, building a wall, for example. One becomes capable of comprehending in situ the daily labor done by slaves to create the Wall that stands physically before her today. In the process, she relates to the built environment differently. She “sees” a division of labor rather than just an old wall. A new habit of thinking is made possible.

Image Credits:

1. South Carolina College, ca. 1850. (Credit: South Caroliniana Library.)

2. Historic brick. (Credit: H. Gordon Humphries.)

3. Sesquicentennial commemorative plaque.

4. The Wall. (Credit: University of South Carolina.)

5. Ghosts’ AR interface 1 and 2. Dr. Susan Courtney (Film and Media Studies) and computer science student Andrew Ball. (Credit: University of South Carolina.)

6. First Stewards Hall, ca. 1820; voice enactment of Henry, an enslaved carpenter purchased by SCC in 1829 for $700.00. (Credit: South Caroliniana Library; interpretive monologue scripted by graduate student Jess Tompkins and performed by Dontavius Williams, historical interpreter.)

Please feel free to comment.

- See: “Slavery at South Carolina College, 1801-1865: The Foundations of the University of South Carolina.” [↩]

- Roland Barthes. Camera Lucida: Reflection on Photography. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Will and Wang, 1981. [↩]

- Ghosts of the Horseshoe is based on the robust scholarly website “Slavery at South Carolina College, 1801-1865: The Foundations of the University of South Carolina” (see footnote 1). A prototype of the Ghosts application was presented and demonstrated on December 4, 2012 by undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in a cross-College course called “Critical Interactives.” The project has received bridge-funding (USC College of Arts and Sciences) and an internal ASPIRE II grant (USC Office of the VP for Research). The University Libraries hosts the server that houses the Ghosts database and website (http://calliope.tcl.sc.edu). Please see the website to view a short video and a local WIS television segment about the project. [↩]

- See: “Buildings as History.” University Map. University of South Carolina website. [↩]

Pingback: Habit-Change in the Mobile Present III: Augusta App and Habit-ing Differently Heidi Rae Cooley/University of South Carolina | Flow