The Medical Gaze, Your Health and You Black Hawk Hancock / DePaul University

In my previous article, I considered medical advertisements, specifically those calling upon the spectator to “ask your doctor,” in relation to the larger context of healthcare in the U.S. Here I want to call attention to the ways that direct-to-consumer advertisements (DCTA) work as mirrors to induce us to think about ourselves as bodies, as selves, as patients, and as consumers. Philosopher Michel Foucault, once used the term “the medical gaze” to describe the detachment or dehumanization of the body into an object of analysis, to be probed, analyzed, and examined, becoming the basis upon which medical knowledge was developed. 1 Extending “the medical gaze” to DTCA helps draw out the ways that advertisements operate to expand that gaze into every aspect of our lives, as well as to help us question the trajectory that development takes.

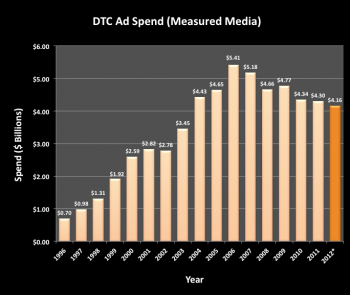

DTCA is a well-researched field of inquiry. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising (DTCPA) has grown rapidly during the past several decades and is now the most prominent type of health communication that the public encounters. Spending in the US for prescription drugs was $234.1 billion in 2008, nearly 6 times the $40.3 billion spent in 1990. From 1999 to 2009, the number of prescriptions increased 39% (from 2.8 billion to 3.9 billion), compared to a US population growth of 9%. Manufacturer spending on advertising was over 1.5 times as much in 2009 ($10.9 billion) as in 1999 ($6.6 billion). Human Health Services projects US prescription drug spending to increase from $234.1 billion in 2008 to $457.8 billion in 2019, almost doubling over the 11-year period. 2 Proponents of DTCA argue for how advertising informs, educates and empowers individuals to take control of their health. In addition, it encourages patients to seek out medical advice, to promote dialogue with their physicians and healthcare providers, and reduces underdiagnoses and the undertreatment of conditions. 3 Commonly voiced arguments against DTCA claim that advertising overemphasizes potential benefits, wastes appointment time, strains relations with health care providers, leads to inappropriate prescribing, and promotes drug use before safety profiles have been fully established. 4

However, the pros and cons of DTCA are side issues compared to the dominant issue confronting public health—medicalization—the ever expanding definition of human conditions, which previously were non-medical issues, and are now problems in medical terms requiring medical intervention. While advertisements often appear to clarify and educate, they purposefully confuse people, causing them to redefine normal aspects of their lives in medical terms, which in turn creates greater demand for a medical product. 5 As a result, medical products “create” their own markets through convincing consumers to seek medical treatments which actually might not be needed, with medicalization as the by-product. Technological advances and consumer desire for these new treatments, especially as they become more available and affordable, provide entry into the way that medicalization not only redefines human conditions in new medical terms, it redefines human subjectivity as well.

As part of the social fabric, medical DTCA becomes part of the social conversation which we have about ourselves and others (media not only socializes us, it connects us to the contemporary conversation of what we consider important, interesting, noteworthy, etc…). By linking medicalization, DTCA and subjectivity, we can see how the medical gaze gets extended onto and into us as both consumers and patients. Here advertisements work not as tools of domination, rather they serve as mirrors which reflect back to the observer one’s own condition or possible condition. The advertisement makes certain claims upon the subject that confronts it; it encourages one to self-gaze, to self-diagnose, and to self-evaluate as bodies and selves on the one hand, and as patients and consumers on the other. In doing so, DTCA prompts us to consider our susceptibility to a particular condition, or if we may already have a specific condition that if treated, could make one feel better, or if untreated, could get worse. The ever-escalating medicalization of society does not diffuse these concerns; rather it amplifies them by normalizing the terrain of everyday social life as one of health and illness, normality and deficiency.

DTCA asks one to consider if one is sick, if one is susceptible to certain conditions, and in doing so, draws upon vague descriptions of the medical conditions that could easily be used to characterize a gamut of everyday emotions and symptoms. Worries become classified as “social anxiety,” sadness becomes “clinical depression,” inattentiveness becomes “ADHD,” sleepiness becomes “narcolepsy” and emotional lability becomes diagnosed as “premenstrual dysphoric disorder,” as one or more conditions of our everyday lives become redefined through medical diagnoses and medical treatment. Whether we “ask our doctor,” become informed consumers who desire a “pill for every ill,” or talk in concerned terms that we are “overtreated” or “overdiagnosed”: medicalization has not just become a biological-social construction of a physiological condition, it is constitutive of the ways that we speak, and thus conceptualize the world within which we live. That everyday people have internalized the medicalized messages and medical-speak of DTCA, even at the most basic level, is testimony to the pervasiveness and effectiveness with which the medical gaze has become refracted through DTCA to normalize and regulate the body as a medical one.

By conceptualizing the myriad of ways that the medical gaze becomes inculcated into us, in this case DTCA, we can begin to see a much wider network of relations—from the industry of production, to the mediated and private markets of consumption, to the consumer-patient perceptions, decisions, and behaviors—all which serve to normalize and regulate those bodies through the medicalization of social life. Countering this requires bringing together the ways that consumer-patients self-evaluate, self-analyze, and self-diagnose their conditions relative to their bodies as medical objects on the one hand, and their selves and identities as people on the other. However, this is not a return to a “pre-medical” understanding or a call to cultivate an “anti-medical” politics. Rather, by starting with the ways that the medical gaze operates, through which lifestyles are understood and decisions made, that the contemporary relationships between advertising and consumer beliefs can be understood as contributing to advancing ever new forms of medicalization.

As Cultural Studies scholar John Fiske used to remind many of us, it is often here, in asking the questions that we assume are all too obvious, that we may “find a point of purchase” by which to drive a wedge into these issues and open up their dynamics for critical interrogation. As Fiske would also point out, we must not lose sight that Foucault’s medical gaze was the basis upon which a new model of knowledge emerged; one which may appear inevitable, yet is always open to the question of how it can be changed.

Please feel free to comment.

Image Credits:

1. Stanford University

2. Pharma Marketing

3. SodaHead.com

- Foucault, Michel. 1963. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. New York: Vintage Books. [↩]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 2010. Prescription Drug Trends Report. [↩]

- Frosch, D..L, Grande, D., Tarn, D.M., Kravitz, R.L. 2010. “A Decade of Controversy: Balancing Policy with Evidence in the Regulation of Prescription Drug Advertising.” American Journal of Public Health. 100(1):24–32. [↩]

- Almasi, E.A., Stafford, R.S., Kravitz, R.L., Mansfield, P.R. 2006. “What Are the Public Health Effects of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising? PLoS Med. 3(3):e145. [↩]

- Conrad, Peter. 2007. The Medicalisation of Society: On the Transformation of Human Conditions into Treatable Disorders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [↩]

Pingback: Direct-to-Consumer-Advertising and the Archipelago of Medicalization Black Hawk Hancock / DePaul University | Flow