Act your Race, Not your Age: Performativity and the Many Faces of Comic-Con Cosplay

Keara Goin / FLOW Senior Editor

2012 San Diego Comic-Con Logo

I went to the 2012 San Diego Comic-Con (SDCC) with a mission to seek out and identify those fans who took the practice of “cosplay” (or costume play) to the racial extreme: black-face, brown-face, yellow-face, or red-face. However, while I did not find such instances (which came as a very real surprise to me), I nevertheless found proof that, as it is said, “race matters” in the realm of stepping into a cosplay character. While I might not have seen any black-faced Uhuras (Star Trek), I did notice a few distinct trends that revealed the importance of race in constructing a fictional subjectivity in both exnominated and nominated fashions. Specifically, I discovered the following racialized practices: (1) donning the mimetic facade of a character that one would consider of the same race as oneself, (2) the use of non-“realworld” skin paint—blue, red, orange, silver, etc.—to be able to indulge in racial cross-dressing without the baggage of racist accusation, and (3) the practice of what I am calling “alien-face” or “zombie-face” as a means to embody the pop cultural Other.

Group of Cosplayers

By sticking to the seemingly safe identification with characters that are perceived to be of the same race/ethnicity as oneself, cosplayers attempt to negotiate the anxieties concerning the trangressive nature of cosplay. As an activity that is by nature based on escaping one’s identity to live out a short-term fantasy as (an)Other, it seems that characters are chosen not on fandom based reasoning alone. For example, thousands of attendees of this year’s SDCC were fans of Star Trek, but I only saw one person dressed as Geordi (portrayed by actor LeVar Burton) and it was by a black man. The same situation is seen in the case of a black woman dressed as Zoe from Firefly (portrayed by actor Gina Torres). What is essentially occurring as a result of a society that is both racist and repressive, is a racialized performative mimesis of character identity as an appropriate practice of pop cultural cosplay. And while transgressing gender through the characters one chose to embody was a common sight, crossing into another race was strictly avoided. Whether it was Asian attendees dressed as popular anime characters or white fans suited in Battlestar Galactica uniforms, cosplayers seemed to draw the line at racial transgression—or did they?

While I did not see examples of blatant racialized/racist cosplay performativity as exemplified in U.S. historical minstrelsy, I nonetheless insist that race played an essential role in the fantasy identity play that constructs cosplay reality. Maybe their face paint was not black or brown, but it was still blue, silver, red, or gold. These body painting practices reflect back on the hegemonic centrality of skin color in identity and categorization, one so ingrained in the way we think about subjectivity that it is difficult to even notice when we are indulging in it. It serves to reason, that behind the physical application of such out-of-this-world pigmentation, lays an assumption rooted in the perceived significance of one’s skin color as a fundamental component constituting who one is. Furthermore, as such instances of performativity were not overtly seen as racist—as the races alluded to are fictional and alien ones—cosplayers are provided with an escape hatch from the taboos and prohibitions associated with racial cross-dressing. Black-face, in its own time, was once popularly thought of as a trivial and meaningless practice; is it the same for these paintings of the skin in colors that do not correspond to actual skin colors found on Earth? Are silver and blue the new black/brown face? I assert, that while the symbolic violence (Stuart Hall) is not as clearly directed at racialized groups compared to more historical representations of racialized painting of the body, it is still a factor in the articulation of such occurrences of performing the Other.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XjoEkF79aE[/youtube]

The painting of one’s body in a fashion that is supposed to reflect the essence of the character is only a part of the whole package of cosplay performativity, which also encapsulates costuming, hairstyling, behavior, speaking style, and gesture. As such, the use of extra-terrestrial body makeup is a fundamental example of how it is not only whiteness that is exnominated, but fantastical bodies as well. However nonsensical that might sound, by cosplaying in blue body paint instead of brown, for example, the character performer distracts everyone around them from focusing on their actual race which becomes normalized in comparison to that which is fabricated on their person. In the process, the power of the normative human body becomes obstructed from our sight and we become engulfed in the fantasy of racelessness. It is not until one overtly transgresses the limits of normative and acceptable subjectivity into the realm of the Other—puts it on like a ill-fitting pair of jeans—that the racialized nature of extra-worldly cross-dressing becomes clear.

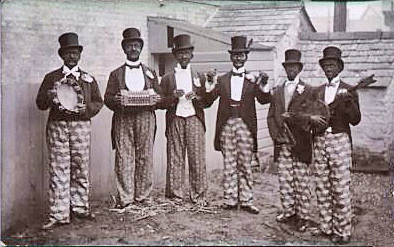

Black-Face Minstrel Performers

While fandom can be a wonderfully enjoyable and creative engagement with the appealing world of pop culture, at the same time it is often a hornet’s nest of social tensions, anxieties, obsession, fetishes, and fears. As such, the exercising and negotiation of said social realities within the performative nature of cosplay reveals the ingrained status of racial essentialism within commonsense notions of identification and subjectivity. Not to wax overly psychoanalytical, but as an assertion that I feel most people recognize as logical, cosplay is an escapist performance of one’s fantasy. Furthermore, this performance, while not sanctioned in the “realworld,” is fully acceptable in the realm of the SDCC. As an alternative to the realworld, SDCC has alternative Others one can embody as part of the fantasy of cosplay. Moreover, with the long-term popularity of cosplaying images of aliens combined with the more recent phenomenon of zombie cosplay, an emerging sense of alien-face and zombie-face becomes a veiled exercise of appropriating the Other, one that is directly reminiscent of racist black-face performativity.

Creator of The Walking Dead Robert Kirkman with Zombie-Faced Cosplayers

So what do we make of cosplay practices that use such bodily painting techniques? Surely we cannot chastise the Avatar fan for dressing in a blue leotard with their face and arms painted blue? My answer to that is a reminder of how important it is to ask ourselves why when we feel compelled to dress as the Other. As a seemingly harmless and therefore trivialized activity, the popular donning of zombie costuming is frequently accompanied by the now iconic body makeup mimicking the aesthetic of the walking dead, decomposing and oozing what remains of their humanity. And while the performer in zombie-face might not intend to or be cognizant of a racialized painting of their body, such practices nonetheless draw from the legacy of black-face performance. New cultural phenomenon is not created in a vacuum, but built onto the foundations of already existing cultural structures—a process that often obscures the origin of such cultural practices and artifacts. Consequently, acts of zombie-face, and the more extended use of alien-face, are rooted in minstrelsy era racial performativity, which functioned as a means to confront the social anxieties and tensions of that historical moment. While I am not trying to make a judgment against those who enjoy and find great fulfillment in the practice of cosplay, I do contend that before taking up the Other as a performance of one’s fantasy, ask yourself why do you want to look like a disgusting, gross, rotting zombie?

Image Credits:

1. Comic-Con 2012 Logo

2. Cosplayers

3. Black-Race Minstrelsy

4. Zombie-Face Cosplayers

Please feel free to comment.

Great article Keara. Thanks for taking a critical look at the ways in which the act of painting one’s face and body in order to embody a kind of otherness can re-inscribe racial hierarchies. It is particularly illuminating to think about the ways in which coloring one’s skin allows an outlet to express something about the other that would otherwise be too transgressive without the benefit of alienface or zombieface.

Interesting piece overall. I do feel your analysis on zombie-face and alien-face is overstretching though. Such identities are racialised, I agree, but I do not see any direct link to black-face. In fact, I see such play is an extension of what you describe above, ie, staying with one’s own racial boundaries. The rotting, oozing zombies in the image you provide look like white zombies as the majority do on The Walking Dead, with a few minority zombies thrown in. As for the alien-face, skin color is only one marker of racial identity. I haven’t see the cosplay you describe but I suspect much of it would be associated with whiteness. Black face on the other hand is a racialized practice meant to demean the culture of black folk and had real effects. One cannot draw a parallel with zombies and aliens unless there is evidence of coded black face performance.

Rhiannon, thanks for your comment. I can see where your see a disconnect between black-face and zombie-face in terms of the sentiments behind each practice. You are absolutely right that the practice of black-face was based on an intended demeaning and denigration of blackness whereas the practice of zombie and alien-face is more rooted in admiration and fantasy. Where I see the connection is in the using of the other, in both cases, as a costume to explore otherness in a way that deals with social anxieties concerning race. Skin color might not be the only factor in racial classification, but it is the most visible and obvious one in US systems of racialization. And so, it is hard for me not to see it in relation to black-face performance, an institution that has left deep-rooted traces in a wide range of US cultural expression. I see these instances of cosplay as the individual negotiation of cultural texts manifested in racialized ways on the body (whether or not this in relation to whiteness, blackness, latinidad, you name it), very similar to other kinds of physical mimicry and appropriation all too common in US culture.

Each year I invite college students from across the country to come join me for a field study program called “The Experience at Comic-Con,” which examines fan behaviors at Comic-Con International, and each year one or more students delve specifically into the realm of cosplay. I will be sure to recommend your thoughtful piece to my students and invite their comments on your reflections. Thanks for sharing!