David Lynch’s Wholes

Akira Mizuta Lippit / University of Southern California

In his cinema, David Lynch regularly divides the world into separate sides, halves, dimensions, fragments that appear to be formed along conventional lines of opposition: past and present; high and low; day and night; light and dark; the beautiful and the monstrous or grotesque; the straight and narrow and wide and twisted; the abstract and figurative; the local and the global, even universal; the innocent and the guilty; the pure and the stained; good and evil; TV and cinema, but also painting, photography, and various other audio-visual media; the actual and metaphorical; melodrama and horror (genres); the material and the spectral; this and that. For Todd McGowan, following Slavoj Žižek following Lacan (the kind of mise-en-abîme that drives Lynch’s cinema toward a point without origin or destination), Lynch’s films operate according to a split between the “realms” of desire and fantasy.1 Such divisions are themselves familiar, not only in cinema but throughout numerous modes of thought, ideology, culture, and representation.

“We all have at least two sides,” says Lynch. “The world we live in is a world of opposites. And to reconcile those opposing things is the trick. … And that means there’s something in the middle. And the middle isn’t a compromise, it’s, like, the power of both.”2 Lynch’s middle becomes a threshold between sides, the beginning of one before another, but also a place itself, an interstitial place without place. On closer observation, these opposing worlds are neither halves nor pieces of the same; rather they are proliferations that do not originate in any source. Nor do they converge, ever, to form a whole. They are phantasms, material dreams, corporeal fantasies, physical spaces, entire worlds that form at a distance from this world. They are autonomous, each one its own threshold. What distinguishes Lynch’s worlds are their incommensurabilities; the divisions are never dialectical (however symmetrical they might at times appear to be), they can never be reformed, restored, and repaired; they are unwholesome, which is to say they never form wholes or totalities. (They become complete and discrete entities in and of themselves, but they never merge with other worlds to create one set of laws, one unified universe.) False halves; irreducible, heterogeneous fragments that never align to form a whole, even if they appear to be contiguous, even if they are forced to share space within a single system. In place of wholes are holes: secret, unimaginable, anomalous moments, modes, and instances of contact between the sides, using various transitional figures.

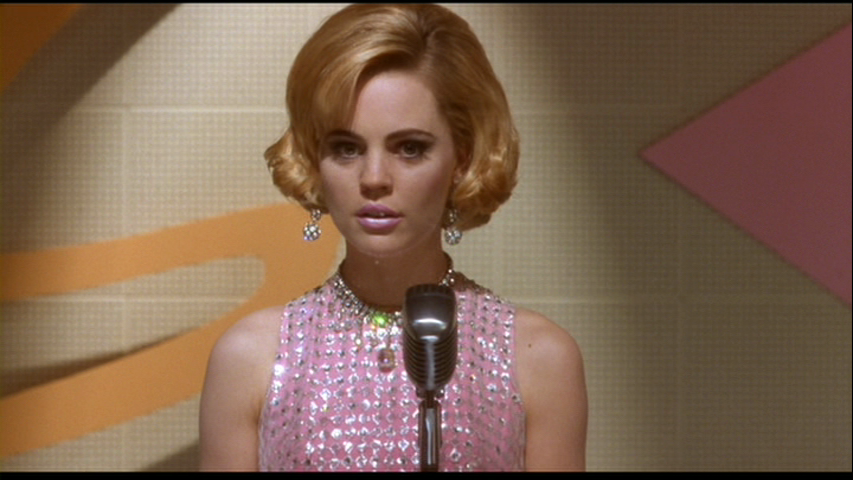

Figures that serve as conduits, mediums, servers, in the culinary and virtual senses. The quasi-human baby of Eraserhead (1977); The Night Porter in The Elephant Man (1980); Ben (Dean Stockwell) in Blue Velvet (1986); virtually every character in Twin Peaks (1990-91)–even and perhaps especially Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), Leland Palmer (Ray Wise), and Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle McLachlan) are transitional characters, as are The Log Lady, the Giant, The Man from Another Place, the Norwegians, Killer Bob, Windom Earle, Leo, FBI agents Gordon Cole (David Lynch), Chester Desmond (Chris Isaak), and Phillip Jeffries (David Bowie), the agoraphobic Harold Smith; and Lil in the red dress in Fire Walk with Me (1992); (Jack Nance each time he appears); The Mystery Man (who never blinks) in Lost Highway (1997); The Cowboy and polyglot MC in Mulholland Drive (2001); the Deer Woman (Barbara E. Robertson) in The Straight Story (1999); all of the Polish elements and the talking rabbits in Inland Empire (2006), as well as the Lost Girl; and the various strangers that appear briefly throughout Lynch’s oeuvre to deliver messages, omens, advice, or merely looks. They pass messages–are themselves passages–between the two sides. They form the Lynch mobs that populate each of his films: catalysts, holes, passages, connections.

They are transients, transit agents and points, themselves transitional, which is to say they do not belong properly to the narrative, or in some instances even to the diegesis. They appear to bridge heterogeneous spaces that do not otherwise allow any contact; once such points of contact are forged, the transitional figures disappear into the elsewheres that form around and envelop Lynch’s fragmentary worlds. These transitional figures are anti-figures or protagonists, devoid of subjectivity, who also put into relief the massive deficits of subjectivity that afflict all of Lynch’s characters. They belong nowhere.

Image Credits:

1. Lady in the Radiator

2. The Cowboy

3. Camilla Rhodes

4. The Rabbits

5. The Lost Girl

Please feel free to comment.

- McGowan says of Lynch’s films, “They create a division between the realm of desire and the realm of fantasy, between the exigencies of social reality and our psychic respite from those exigencies” (Todd McGowan, The Impossible David Lynch [New York: Columbia University Press, 2007], 13). In a footnote to this claim, McGowan further ascribes the split between desire and fantasy not only to Lynch but to the structure of cinema itself: “The division between the worlds of desire and fantasy in Lynch’s films takes place within the larger fantasy structure that is the film itself. Because he presents the world of desire within the fantasmatic medium of film, this world is necessarily a fantasized image of the world of desire” (227). According to this logic of infinite regress, what is made visible in Lynch is already at work in cinema: desire is already framed within the fantastic, phantastic (fantasmatic) medium of cinema. The split between desire and fantasy that Lynch introduces in his films, a split that is sustained until the end, is a secondary division already at work in cinema. [↩]

- David Lynch, Lynch on Lynch, ed. Chris Rodley, revised edition (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 23. [↩]

Pingback: Crítica: Eraserhead – Analisando as profundezas da insanidade – Projeto Cinematográfico