Who Was That Masked Woman? Rediscovering the Hidden Mother

Melinda Barlow / University of Colorado at Boulder

When a friend sent me this link for a Texas newsreel featuring “an interesting mother daughter relationship,” I knew I had hit the mother lode. Knife throwing might be a quaint 19th century amusement, but this 1950s iteration cut me to the quick.1 Instead of a dashing man hurling Bowies at a scantily clad assistant, here was a stolid woman in a day dress, skillfully flinging blades at two unflinching little girls. “Quite the family, the Gallaghers,” quips the jovial voiceover, “Connie Anne, 5 years old, and Colleena Sue, 2 ½, are a big help to mother Luella, who is no mean hand with a handful of knives.” Indeed, this mother outlines each of her daughters with great dexterity, nicking neither one. But it is the possibility of that nick that we wait for, a slip rather than sleight of hand that promises the forbidden thrill of blade piercing flesh, here especially unsettling because the targets are children. Although their smiles are as unwavering as their mother’s concentration, their poses carefully choreographed for maximum theatrical effect, this sideshow act nonetheless feels like a trauma in the making, one capable of wounding our sense of the sanctity of the mother daughter bond.

And yet, as so many films and memoirs consistently attest, from the recent remakes of Mildred Pierce (2011) and Grey Gardens (2009) to that Texas gem The Liar’s Club (1995) by Mary Karr, this relationship is a complex conundrum in art and life, a fierce if not traumatic attachment often fraught with what psychoanalysis by way of classical mythology calls murderous rage.2 Every vengeful Electra has her neglectful Clytemnestra, each self-sacrificing Mildred her ungrateful Veda, and Big and Little Edie’s prickly symbiosis may be a less than flattering mirror for us all.

But none of these volatile mother daughter dynamics holds a candle to that of Mary Karr, whose sharpest childhood memory involves the family doctor urging her to show him the marks left by her mother Charlie’s carving knife when she came after her and her sister Lecia during a psychotic break. Hallucinating that she had butchered her children, she called the doctor, who called the law, who hospitalized her for being Nervous. Watching her recount this incident on video years later, Karr sees her younger self ask her mother what she was thinking that fateful night in 1961. “I just couldn’t imagine bringing two girls up in a world where they do such awful things to women. So I decided to kill you both, to spare you.”3

Worthy of a Hollywood film, both line and event are drawn from Karr’s life, but each finds echoes in countless films and memoirs: Joan Crawford as the original Mildred in 1945 shrieks “Get out before I kill you!” at greedy and capricious Veda, and, as Vivian Gornick writes in Fierce Attachments (1987), her mother Bess, provoked by Gornick’s views on marital love, likewise screams “Snake in my bosom, I’ll kill you!” while chasing her daughter into the bathroom and smashing her fist through the glass door.4 If Charlie Karr’s allusion to a feminist-inspired form of mercy killing gives this sentiment a somewhat different spin, it is perhaps because it at once registers the latent female rage smoldering in the early 60s that erupts in The Feminine Mystique (1963) and has been so compellingly rendered by Mad Men’s Betty Draper, seen reading Mary McCarthy’s The Group (also 1963) in the tub—and reminds us that in previous eras the expression of female anger was heavily veiled and deeply culturally repressed. Thus the faint stirring described in two of Emily Dickinson’s most famous lines, “A dim capacity for wings/Degrades the dress I wear,” is in fact a 19th century clarion call to consciousness, if not arms.5

Dickinson, who eventually retreated into her house, wore a white dress, and refused to meet people face to face, came from a world where the cult of True Womanhood reined supreme and chained women to domestic life. Hostages in the home, as Barbara Welter described them in 1966, 19th century American women were instructed by a wide range of magazines and etiquette manuals like Godey’s Lady’s Book in the fine art of remaining unheard and unseen.6 “Working like nature, in secret,” women should obey the four cardinal virtues of piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity, cheerfully yielding to their husbands and serving the needs of their children before satisfying their own.7 That “cloak of the heart” good manners was essential to this process. “If politeness is but a mask it is still better worn than cast aside,” insisted one such primer in 1860.8 Avoiding emotional extremes of all kinds also fulfilled middle-class codes of propriety by limiting facial expressiveness, thus turning the countenance into its own disguise.

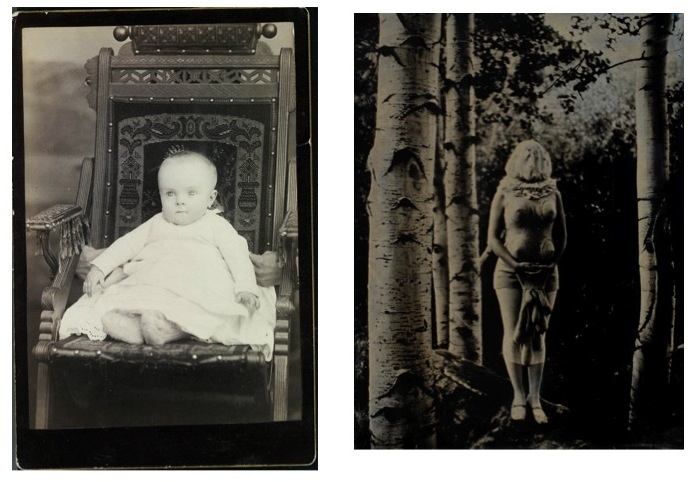

Given the endless references to the importance of dutifully shrouding one’s feelings in these manuals and their reverberations throughout Victorian novels—which routinely erased women by making the ghosts of dead mothers into maternal ideals (Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, 1860) or having them commit suicide when they cannot resolve their internal contradictions (Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, 1899)—it is not surprising that 19th century conventions of photographic portraiture should repeat them as well. But that they do so so forcefully, through such uncanny iconography, often performing a double erasure within a single image, comes as quite a shock, as this riveting example of what is now known as a “hidden mother” tintype makes clear. When I found it online, it made me shiver and think grim reaper. Who was that masked woman? What happened to her baby? Haunted by maternal presence, this photograph discloses its absence, and may have hidden it yet again behind an oval mount or by tucking the photo into a tiny case. Contemporary literature on the subject seals this woman’s fate with a certain finality: referred to as cloaked female “attendants,” women like this one, who held their children still for the duration of an exposure, were covered to keep the focus solely on the child, their anonymity further insured when their faces were scratched out or cropped off by the edges of the frame.9 Like the woman who has lost her head in Empty Dress (2007), an altered 19th century photograph by Francois Deschamps, such women remain nameless and without individuation, forever draped in an unintended costume that divulges a deep secret: maternal absence is a dynamic signifying presence, a cultural trauma palpable precisely because it comes from something unknown, that seems not to be there.

The roots of this trauma run deep, its ideological stakes are high, and its cathexis ricochets vigorously into our own century, coursing through art, films, and recent tintypes each able, in Roland Barthes’ phrase, to assail us with its own punctum, each, like knife throwing, a unique impalement art capable of piercing us to the core.10 Contemporary work that returns to mid-20th century images of femininity does this by shattering its peculiarly placid veneer with startling alacrity, unveiling visions of family harmony, exposing the monsters lurking beneath what Betty Friedan called the “smiling empty passivity” required of women when the cult of domesticity returned in the 1950s, and both confronting and cherishing fantasies of mother daughter symmetry through strategies which reveal their hidden other side.11

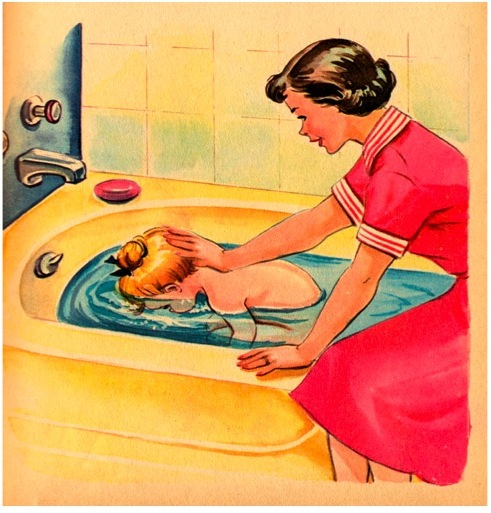

In Laura Shill’s The Happy Family #6 (2006), for example, a beaming mother presses her daughter face down into a bathtub, cheerfully helping her drown. Does this chilling image present another feminist mercy killing, like the one described by Charlie Karr? Or, as one of those pictures that “would never make it into the family album,” as Shill notes, does it reveal a world whose characters may be “unwittingly evil, and completely oblivious of their own cruelty?” Emerging from a time and place that pre-exists irony or cynicism (the image prior to Shill’s alteration is part of The Little Swimmers, a charming yet saccharine childhood classic from 1960), the series is intended as “a repudiation of the notion of ‘the good old days’”—that euphemism which skillfully masks such repressive social forces as conformity, sexism, and segregation.12

Sweeter in tone is the nested tintype Untitled Box #1 (Easter Sunday) (2011), made from a snapshot of Shill’s mother and grandmother in matching outfits complete with bonnets circa 1960, posing for the camera by displaying their full skirts, performing their twinned selves with savvy self-consciousness and clearly enjoying the experience of dressing up. More aggressive is Untitled Box #3 (Beverly’s Weapons) (2011), which features the same grandmother in cowgirl attire aiming a rifle right into the lens, nestled in a locket hanging in a small box, here held in close up in Shill’s hand. That Shill used to play dress up in Beverly Ball’s closet when she was a child is telling. It suggests a cross-generational thrill to theatricality, a shared pleasure in costumes and deliberately hamming it up in front of the camera that is in fact part of the legacy of the tintype. In 19th century America, people of all classes regularly mugged in special outfits with self-chosen props for the itinerant photographers who passed through town, in the process flaunting a theatrical sense of self that broke with codes of middle-class bodily propriety and traversed traditional gender boundaries. Given this context, Shill’s gun-toting grandmother seems like a long overdue refusal of 19th century rules mandating genteel female gestures, and an iconic mid-century answer to Emily Dickinson’s subdued call to arms.

In hidden mother tintypes women’s gestures, although customarily cropped out by mats and mounts just like their faces, were often perceptible beneath veiling blankets, and seen reaching in like phantom limbs from out of frame, a convention that persists in amateur films shot one hundred years later. That dark figure with a gaping maw in the ‘grim reaper’ photograph is carefully supporting a rather startled child, and the tension between her steadying hands and swallowing lap is dramatic. In other hidden mother cabinet cards and in home movies, there are glimpses of female arms and hands propping children up, giving them a prod from off screen (She/Va, 1973), directing them to smile and smell the flowers (o little jeannie, circa 1950), and clasping them tightly while crouching behind ornate chairs. In view of the 19th century assumption that it was a woman’s solemn responsibility to “uphold the pillars of the temple with her frail white hand,” as Barbara Welter put it, and a mother’s job to shape “the infant mind as yet untainted by contact with evil,”13 malleable as wax as it was beneath her “plastic hand,” as Ladies’ Companion advised in 1838, these remarkably sturdy female gestures should be treasured in all of their stabilizing iterations.14

Eventually, however, they must be relinquished, for every child has to put her mother behind her, leaving the security of that comforting yet claustrophobic lap to stand on her own two feet and face the future alone. The sensation of doing so, of feeling “neither cut off from the past nor mired in it,” in Mary Karr’s phrase, can be nothing short of exhilarating.15 As the child one was turns toward twilight, the woman one will become points in a new direction, poised on a rock, ready to disembark, unable to foresee what her life has in store, her capacity for self-creation now in her own hands, her mother hidden within.

Thanks to Benjamin Janek for his invaluable aid with this essay. Dedicated to Judith Bowles and in memory of Mary Teresa Clark, and inspired by the work of Laura Shill. You all enabled me to see.

Image Credits:

1. Luella Gallagher in Knife Throwing Mother (1950s), Texas Universal-International Newsreel

2. Colleena Sue Gallagher in Knife Throwing Mother (1950s), Texas Universal-International Newsreel

3. “The Best at Home,” Godey’s Lady’s Book, mid-19th century.

4. From left: Anonymous Hidden Mother tintype, 19th century. Francois Deschamps, Empty Dress (2007). Both collection of Melinda Barlow.

5. Laura Shill, The Happy Family #6. Collection of Melinda Barlow.

6. Laura Shill, Untitled Box #1 (Easter Sunday) (2011), detail. Collection of the artist.

7. Laura Shill, Untitled Box #3 (Beverly’s Weapons) (2011), detail. Collection of Melinda Barlow.

8. From left: Anonymous Hidden Mother cabinet card, 19th century. Collection of Melinda Barlow. Anonymous home movie retitled o little jeannie (circa 1950), collection of Jeanne Liotta. Marjorie Keller, She/Va (1973).

9. From Left: Anonymous Hidden Mother cabinet card, 19th century. Collection of Melinda Barlow. Laura Shill, Untitled Performance #6 (2011). Collection of Melinda Barlow.

Please feel free to comment.

- The You Tube link sent to me by Laura Shill titles this newsreel Knife Throwing Mother 1950s. On the Texas Archive of the Moving Image website the title is Knife Throwing Family (http://www.texasarchive.org/library/index.php/Knife_Throwing_Family) and on the site for the Prelinger Archives it is Knife-Thrower and Children (ca. 1950) (http://www.archive.org/details/KnifeThr1950). [↩]

- The original films are Mildred Pierce (dr. Michael Curtiz, 1945) and Grey Gardens (dr. Ellen Hovde, Albert and David Maysles, and Muffie Meyers, 1975). The remakes were directed for HBO by Todd Haynes in 2011 and Michael Sucsy in 2009, respectively.

For a psychoanalytic overview of love/hate relationship between mothers and daughters, see Henrika C. Freud, Electra vs. Oedipus: The Drama of the Mother-Daughter Relationship, trans. Marjolijn de Jager (Hove, East Sussex, UK: Routledge, 2011). [↩]

- Mary Karr, The Liar’s Club (New York: Viking Penguin, 1995), and Mary Karr, Lit (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009), 3. [↩]

- Vivan Gornick, Fierce Attachments (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987), 110. [↩]

- The poem is titled “From the Chrysalis,” first published in 1896.

My cocoon tightens, colors tease,

I’m feeling for the air;

A dim capacity for wings

Degrades the dress I wear.A power of butterfly must be

The aptitude to fly,

Meadows of majesty concedes

And easy sweeps of sky.So I must battle at the hint

And cipher at the sign,

And make much blunder, if at last

I take the clew divine. [↩] - Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1960,” American Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 2, Part 1 (Summer, 1966), 151-174. [↩]

- Maria J. McIntosh, Woman in America: Her Work and Her Reward (New York: 1850), 25. [↩]

- Forence Hartley, The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette, and Manual of Politeness (Boston: G. W. Cottrell, 1860), 3. [↩]

- The two major books on tintypes are split in what they call hidden mothers. In Floyd Rinhart, Marion Rinhart and Robert. W. Wagner, The American Tintype (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1999), 75-75, reference is made to actual mothers, but in Steven Kasher, America and the Tintype, reference is made to the cloaked “attendant” on page 67. [↩]

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Inc., 1981 [↩]

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1963; reprinted 2001), 118. [↩]

- Laura Shill, email to the author, 9/17/11. [↩]

- Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” 152. [↩]

- Mrs. Emma C. Embury, “Female Education,” Ladies’ Companion, VIII (Jan. 1838), 18. [↩]

- Mary Karr, The Liar’s Club, xiv. [↩]

The film itself comes from a group of 35mm newsreels collected by a San Francisco Bay Area collector, who typically kept only California “local” stories but seems to have made an exception for this one. I made up the title we provide for the Internet Archive version, as there is no apparent story title. Universal Newsreel typically filled out its semi-weekly reels with brief stories that lacked the usual newsreel story titles and were simply introduced by their location. The YouTube version is a copy of our Internet Archive version.

I am most struck by the hidden mother tintype, “a dynamic signifying presence…that seems not to be there.” In the cultural swirl surrounding this absented visage — of knife-throwers and gun-toters, prodding hands and wicked daughters — I keep returning to the empty face and erased hands holding the pale child. After staring at the strangely pyramidal woman, reduced to black sculpture, I begin to see her as a dark icon, a strangely Protestant elision of the maternal presence. Instead of blessed maternal fecundity, we are left with something like an ominous shadow, only heavier. It seems such photographic maternal erasure works to eliminate the body most of all, to sever the material, blood and flesh connections between mother and child — an action that feels like an unintentionally subversive attempt to recover immaculate conception. Instead of being born in light, however, the mother’s lap becomes a concealed enigma. The bodily harm threatened between mother and daughter, between Mildred and Veda or Luella Gallagher and Connie or Colleena Sue, seems a distraught effort to reconnect the maternal with the daughterly body.

If you look into the past there are multiple instances of men paving the pathway to success for their young boys, whether it be taking them on their first hunt, taking them as an apprentice or through male-bonding activity. There is an exchange between the mother and father when a boy reaches a certain age where he stops being nurtured and has to become a “man”. Historically this exchange never takes place for a daughter, as she would go from her father’s house to her husband’s house. The daughter like the mother was the commodity of the economy of the household. In a way, especially in the 19th century where women weren’t allowed to own property until mid-century, daughters were the only thing a mother could own. They like their mothers were kept in solitude and became the voiceless ornaments of the households. In adolescence, we see the struggle between mothers and their daughters begin. As the daughter becomes sexual and her value as a commodity goes up in the outside world, the struggle between the mother and daughter grows exponentially, until the daughter is traded by the father into the arms of another man where the cycle begins again as the daughter becomes mother and begins brooding.

Though women now have more options than they had ever had before, many of our mothers/grandmothers did not have the opportunities that we do now, and that alone creates tension. Women have been regarded for a millennia as the shrouded support that holds the family together but like a beam that holds up a building they have been hidden and here in this article we are able to see the scratches, nicks and wounds that this hidden support can give.

As shown in this article we see this guiding hand telling the young girl to smell the flowers and go outwards into the view of the camera, is also the hand that throws knives nearly nicking the young girl. As young girls turn into young women they begin to let go of their mother’s hand, as the mother’s hand becomes more of an ideal, the invisible hand that affects all of us. There is so much more to talk about, but thanks Melinda for writing this very important, thought-provoking article.

The Hidden Mother tintypes are fascinating artifacts. The last one struck me the most because at first, of course, you see only the child. It’s only when you look further that you see the ghostly hands grasping the child on either side. A spooky ghostly image indeed.

Mothers from the postwar era can easily be regarded as the silent and stoic force behind a family — returning to the home in order to support the husband, and be the backbone of the household. Again, it’s only when you look further that you see someone smothered by cultural expectations — someone like Betty Draper, who is closer than you think to having that smooth surface shattered. Laura Shill’s “Happy Family #6” is interesting in this way. Much like Betty and her daughter Sally, who came to mind as I studied this picture, the reality of their relationship is destructive and even dangerous, yet somehow the 1950s and 60s still managed to present mother and daughter relationships with a peppy veneer.

This is what makes the knife throwing video so disturbing, I think… the upbeat narrative voice glossing the situation. Darling Connie Anne and Collenna Sue “helping” their mother presents a distortion of the mothering ideal. There’s so much to this topic, as filmmakers and artists have particularly explored in recent years. Big and Little Edie in the briefly mentioned 2009 HBO film Grey Gardens seem to me the ultimate presentation of the destruction of both mother and daughter in pursuit of society’s expectations.

I see the mother/daughter dyad, as expressed in “Knife Throwing Mother” and many of these other examples, as a compelling, but subtle, and even wistful, one. The father/son dynamic is also expressed throughout mythology, literature, cinema, and art as violent–specifically, murderous and devouring violence (Oedipus and Laius; Saturn devouring his sons; The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, and Her Lover; the list goes on). It’s kill or be killed, for dads.

Luella Gallagher and her daughters, as well as the Hidden Mothers and Big Edie (not to mention other archetypal cases, like Rapunzel’s witchy foster mother, Joan Crawford’s other defining maternal role as the abusive and controlling Mommie Dearest, or Little Eva’s monstrously self-absorbed mother in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, strenuously denying her daughter’s terminal condition right up to her dying day), exemplify the anguish of successful maternity: Hold your daughters, but don’t hurt them. Motherhood done “right” means that eventually your precious children will grow up and slip your grasp. Luella stops short of making contact with those knives, and of fulfilling the inherent prophecy of those stylized angel wings (which also resemble twin tombstones!) painted on the board behind her daughters. They won’t be sent to Heaven today; instead, they’ll scamper off to join the throng of older girls and young women gathered to thrill at this spectacle.

When the delicate trick of supporting without confining, killing, or being seen to support isn’t pulled off, we get daughters like Little Edie Bouvier, stunted and trapped in her childhood home, or mothers like Charlie Karr, opting for what seems like the kinder course. And as you note, Melinda, we can usually see the mother’s hand somewhere in the frame, especially if we know where to look. For all three of the Gallagher girls, as for most mothers and daughters, it seems the trick is to get through the experience with a smile on your face, and without leaving scars. And the crowd of women and girls watching them will inevitably be disappointed, because even if the trick is managed, watching it done isn’t the same thing as learning how to do it yourself.

From my first time viewing examples of the hidden mother tintype, they have played on my mind; disturbing, haunting and sad. And I wonder how many of these photos from the past, perhaps in my own family archives, contain a hidden mother or “female attendant” who were somehow understood to be content to be covered so that the child could claim all the attention. I still need/want to look for such examples. One can understand the technical reason for the cloaking when the photographic process from the era is explained but somehow that seems inadequate justification for the complete and deliberate erasure of the mother figure while we know she is still there.

It certainly forces us to confront and consider how women have always been expected to be in the background while their children command the centre of attention. And, more importantly, to consider what it takes (and takes away from one’s self) to do this for such a large period of one’s life. Even today, a mother who puts anything ahead of that priority is still regarded as selfish. She may not be cloaked, or phsically hidden or cut out of the picture but her own life’s work becomes her children and her own needs are just as hidden.

I find the juxtaposition of the hidden mother tintypes with, particularly, the knife throwing mother and the Happy Family cartoon to escalate the tension between motherhood and having a life of one’s own – from being hidden to finally exploding with smiling rage (Happy Family) or the adorable children whose mother throws knives at them (Knife throwing mother). Is this what happens when mothers are hidden? I can think back to my own childhood and despite the self absorption of the time many instances come to mind where I was well aware that my mother was hiding her own needs and emotions in order to put our own first. But while hidden they were always there.

Melinda–

I’m struck by the invisibility of this particular discourse/dynamic which, until pointed out in your provocative piece, has eluded me, despite plenty of exposure to the Cult of Womanhood and 19th century ideologies about white middle-class motherhood. It’s stunning how often we look at photographs without really seeing what’s there or not there. Your article makes me want to hunker down with old family photos (both ancestral and from childhood) and re-examine them with the new lens you’ve provided. The piece also raises new questions, as well, one of which was touched on by Joan Fennell above: What other female figures–female attendants, servants or slaves who served as mother figures–have been elided from both the literal and metaphorical picture? How do I read the disconnected hand which both disembodies the mother and invokes the hand that our mothers have in raising us? And how do I parse the complicated feelings invoked by the chilling photos you’ve reproduced here–particularly the image of Colleena Sue Gallagher and The Happy Family? Thank you, Melinda, for the gift of your sight/insight.

Melinda,

As Joan Gabriel mentioned, I am also interested in how the “hidden mother” framework might apply to other female attendants such as the “mammy” (esp. reflected in Southern melodrama) and, given the psychoanalytic tinge here, Freud’s own much-beloved and fetishized nurse/nanny, a structuring absence and signifying presence if there ever was one, which Anne McClintock has written about in detail; what to make of the complex set of emotions one has for the multiple, disparate, often overlapping maternal figures that one encounters/imagines along one’s life? Shifting tectonic plates of motherhood! (Guy Maddin must be making a film about this very phenomenon as I type this). And what happens when these mothers are not only scratched out of an image, or covered by a thick blanket, but actually cease to exist? Do they reside within us in the same fashion? Contained only in memories, do they suddenly demand a greater place in our consciousness?

I really enjoyed the thoughtful complexity offered in this article as it relates to the nuances of mother/daughter relationships, and the role of women in society. The use of the photographs is exquisite in illustrating the different points of conversation.

The picture of Colleena Sue with clasped hands and cherubic smile as her mother is throwing knives at her, seems to say, ‘I love you, Mama–please don’t hurt me!’

The tintype picture of the Anonymous Hidden Mother and the photograph of the Empty Dress, certainly allude to the invisible nature of being a mother and wife, as an expected, but not a particularly celebrated form of womanhood.

While reading this essay, I was also reminded of the recent documentary, Gloria: In Her Own Words, in which Gloria Steinem recounts her relationship with her own mother, saying that her mother’s fixation on politics but inability to act on this passion was a strong, motivating factor in pursuing a life of feminist/political activism. This makes one wonder if a mother’s ostensible passivity, presents an interesting opportunity/challenge for a daughter to pursue in her own life.

The essay concluded on a very nice note, with the reflection that when a child leaves the arms of its mother, she hopefully takes the best of that relationship and steps out into life with the tools to move forward.

Melinda Barlow is ingenious in finding media pieces as well as high art that illustrate the real suppression of American women in the not-so-distant past, and also the murderous rage that exists unconsciously in all of us, in daughters as well as mothers. The job in growing up is of course to use the aggression constructively, to mix it with love, and to be able thereby to live an emotionally full life. No one ever gets it exactly right, and we all regress at times into raw outbursts, inner deadness–there are many places to regress to, defenses to bring to bear. Not giving women the opportunity to go out into the world puts added strain on family life, heats up the aggression in women by denying them a richer range of outlets. When the cultural model of womanhood is the self-abnegating, totally loving mother, there is a special titillation in these contrasting images Melinda has found: the mother as all-giving, the mother as murderer. Both views exist in the unconscious of all of us. Every child has the belief that her mother (i.e.,the world) exists only to satisfy her (or him); and every child must deal with her own rage and the subsequent projected fantasies of the mother as murderer–(I am setting aside the dreadful experiences of children whose mothers really are murderous). A happier, more self-fulfilled woman has a better shot at being “the good-enough mother,” to use Winnicott’s phrase; she can better help the child deal with the fantasies, modify them, tame the instincts, mix the aggression with love and see the world, at least much of the time, as it is. Thank you, Melinda.

Arlene Heyman, M.D. (psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and writer of fiction)

New York City

I, too, am hit by the anonymous hidden mother tintype and am reminded of the ‘invisible,’ draped-in-black kuroko, or the running crew, in kabuki, these figures serving to move props, costumes and various stage-parts mid-performance.

The kuroko, like the hidden mother, exists within our field of vision, in front of us — we see their shadow-like bodies moving around, picking up objects, jetting from all corners of the stage and breathing life into the actor’s performance; yet we do not grant the kuroko an entry into ‘the seen’ due to their narrative absence (they are a formal device, like the cuts between shots in film). We at once acknowledge the kuroko and reject them as “something unknown, that seems not to be there“, as Barlow notes above re: the hidden mother and Empty Dress.

An absence: how can something, so essential to the formation of ‘the seen,’ the performance, so obviously in front of us be transformed, as if by some forbidden alchemy, into a not-there-at-all cipher? If these things where removed the narrative would collapse — there would be no performance, no image. What makes the hidden mother tintype so haunting, for me, is the positioning of the mother as a ‘thing,’ a formal mechanism used to present to us, the looker, a child not hers, but a product of her staging, of her non-existence.

Truly awesome research.

Melinda,

Congratulations on another tour de force! This discussion is provocative and insightful. Your focus on the “hidden hand” of the mother brings to mind EDEN Southworth’s sentimental novel of the same title, which features a (motherless) heroine who rejects domestic conformity and the cult of womanhood. Your discussion also prompted me to think of the postmortem photographs of infants that were so common in mourning culture of the 19th century: the absent child, the present corpse, the absent mother holding up the dead baby and shaping the child into an image of eternal presence. Kristeva’s _Stabat Mater_, indeed.

Brava!

I loved Melinda Barlow’s article and especially enjoyed how she threaded the “hidden mother” image through so many generations and mediums. Coming from a long line of West Texas women, I was immediately drawn in by the film of the knife-throwing mother. Although a woman holding a giant knife didn’t seem that odd (my grandmothers and great-grandmothers were often photographed proudly holding knives –after all, they were the ones who killed the rattlesnakes and butchered the chickens), but watching this mom throw them at her own children all the while accompanied by the cheery voice-over and music of the time was certainly uncomfortable. It was a compelling starting point Barlow chose to guide us through the struggle to find these lost obstructed faces of mothers who either acquiesced to society and became the invisible backbone of child and family or stepped right out with a knife and a gun — in costume, for entertainment or to save her family.

I would love to read and see more!

So interesting to see this treatment here of the knife-throwing woman, as i myself utilized the very same footage to my own ends in a short piece made for a project of artists working exclusively from the Prelinger Archives (L’air du Temps, 2003). I had chosen the clip specifically to accompany my own authors credit at the end of the piece which was made as a response to the marches taking place against the US invasion of Iraq. I did not read the images through the narrative of mother-daughter relationship at the time-I was mainly astonished to see a female as the knife-thrower and took that as a powerful and skillful stance. which I was pleased to align myself with. Perhaps I was also thinking of Joseph Cornell’s films from The Childrens Trilogy where he uses vaudeville-type footage of a knife throwing act where an “Indian” man is aiming at a “squaw” wrapped in paper so as to shroud her form thereby making his job that much more difficult. That act is ridiculous (costumed) yet nonetheless disturbing in its possible violence, like watching a magician, male, and his lovely assistant , female, perform seemingly aggressive acts even as we are well aware they are practiced and constructed for our entertainment. LIke Snowden mentions, I myself was in thrall to the spectacle and the bevy of girls who surround the knife-throwing woman, like a greek chorus of maidens supporting their fierce goddess and learning perhaps how to focus intense and aggressive energies with eagle eye skill by refusing ultimately to bring any to harm. Is she Durga the goddess mother and protector who rides a tiger and has ten weapons one for each hand? I like to imagine she and her daughters in cahoots who take the money and run. Also I like her costume; she is Everymother.

This knife-throwing mother newsreel footage is astonishing and horrifying. I can only imagine the nightmares those little girls must have had. I’m struck, too, by the fact that the on-screen audience for this macabre demonstration is made up of children — all girls, in fact. Did this stunt function as a weird cautionary display for girls? At the same time, it’s always interesting to see women wielding weapons in film. This mother seems to possessed of a grim determination — and too, she aims the knives rather wide — one wonders what drove her to put on this show. I’m reminded of Annie Laurie Starr in GUN CRAZY, a more sexualized and alluring non-mother who puts on a similar show with men in the hot seat rather than children.

Laura Shill’s HAPPY FAMILY is tricky — at first look, I identify much more with the drowning child than the perpetrating mother, even though I am now a mother myself. Is identifying with the child just another form of mother-erasure?

Thank you for focusing on mother-daughter relationships for a change. Our culture is too clogged with accounts of father-son melodramas, all the way up to and including THE TREE OF LIFE. Yes: Mildred and Veda! I haven’t yet seen the Todd Haynes made-for-TV remake, but I can’t wait to see how he updates these overwrought archetypes.

I am happy to see my work (“Empty Dress”) in the context of this article and discussion. I enjoy the relationship made between historical images and the work of contemporary artists who mine the past to recycle content. To offer up images that appear historical but would never have been made (drowning a child in 1950!) is to experience the shock of unconscious drives. Anachronisms– by destabilizing the conventions of time and representation– allow the mind unfettered by logic to imagine. By doing that, do we release monsters (as Goya suggested with the sleep of reason) or do we open the doors to new perceptions? The mind’s lust for thought is labile, attaching itself to the easiest mark, moving on in a hurry, scanning the map and at last, through experience, reaching the destination. Melinda, thank you for the map, the experience, and the destination.

Melinda’s shared narrative and provocative images stir both the mother and daughter in me. I identify alternately with protagonists and victims of these dramas. Marked by my own mother’s ambivalence about alternate erasure of herself and of me (hard to accommodate two strong women of adjacent generations) I wonder how much space I am entitled to occupy in my own domestic sphere, and I and keenly observe others for clues. I imagine myself throwing the knives with precision, and as her daughter I am proud both of my mom’s skill and of my own bravery. And what a spectacle we are! Melinda has drawn us into a world that can reveal each of our unspeakable truths, whilst we are seduced by the sheer sensual joy of her language and images. Thank you, Melinda.

Melinda, your eloquent prose and interest in provocative and often frightening imagery seems to mirror my own scholarship, although in very different ways. As you may have guessed, yes we are sisters, and as such our experience with our own mother is similar.

We both continue through our work to attempt to navigate the struggle of women to find identities that can be erased and are erased time and again. You, Melinda do this through visual imagery and beautiful prose, I through case studies of the endless violence against women in conflict zones, whereby their erasure is absolute, final and never metaphoric, as they are literally murdered in genocides throughout the globe.

We are both struck by the difficulties of women finding themselves through what feels like a never ending erasure of women over time and space. As we both fight our own fear of the inevitable erasure that mortality brings to us all, I am struck by your words that “her capacity for self creation now in her own hands” has never been truer than it is now for both of us. Thank you, for being you. Well done and I love you very much.

Melinda Barlow leads us on a sultry, introspective and fascinating journey to try and answer an ambiguous, yet captivating conundrum: “who was that masked woman?”

Each painting and visual art she analyzes is a “creature” within itself.

Ms. Barlow explains the “contemporary work that returns to mid-20th century images of femininity… shattering its peculiarly placid veneer with startling alacrity, unveiling visions of family harmony, exposing… ‘smiling empty passivity’ required of women when the cult of domesticity returned in the 1950s, and both confronting and cherishing fantasies of mother daughter symmetry through strategies which reveal their hidden other side.”

Things are not always as they appear to Melinda; what seems to be a conformist woman in the 1950s belies a sexual -yet repressed- woman of any era. The repressive “I like Ike” 1950s may have seemed banal but soon gave rise to sexual freedom, poetry and jazz.

Ms. Barlow discusses this “series is intended as “a repudiation of the notion of ‘the good old days’—that euphemism which skillfully masks such repressive social forces as conformity, sexism, and segregation.” This is her gift; she is sensitive to the desires of both the female subjects, and to the artists’ themselves.

Ms. Barlow seeks to represent women not as delicate objects, rather as potent and arousing beings who confront a hostile and conformist world. Ms. Barlow has dedicated her career to analyze how love and desire lurks behind what seems ordinary at first glance. She’s amazing and beautiful.

I am extremely thankful for Melinda Barlow’s research and for the discussion that is happening in this forum. As an artist whose work navigates my own personal history as well as a larger cultural history of gender, identity and the objects and images that tell these stories I appreciate the way Melinda weaves together this very potent imagery providing a poetic insight on the notion of the hidden mother.

I appreciate Melinda’s delicate deconstruction of the “hidden mother” tintypes. The repression present in these images strikes a sense of disbelief, it is one thing to read about such practices and to understand 19th century rules of virtue and propriety but these hidden mother tintypes make those words come to life evoking an intense reaction that contains intrigue for their uncanny nature along with intense anger and sadness for these women.

When looking at Deschamps “Empty Dress” I start to think about Barlow’s description of Emily Dickinson in her white dress secluded in her house in Massachusetts. Deschamps image is powerful and as Barlow writes “maternal absence is a dynamic signifying presence, a cultural trauma palpable precisely because it comes from something unknown, that seems not to be there.” The removal of the female form and this shell of a white dress are loaded with the repression that must have filled the pages of Godey’s Lady Book.

After reading this I am forced to think of my own mother and grandmother and see the residue from these rules. My grandmother a classic upper middle class 1950’s housewife always put on a good face and smiled to the outside world and while she truly had a happy marriage and generally good life I also know that she was and is a master of veiling her emotions and needs to suit others. My mother inherited this amazing ability to put on “the cloak of the heart” and mask her own pain in the effort to protect her children and to this day she still does in ways. Not having children I am not able to see the ways I might have inherited these behaviors but I am sure they are present. This sort of social inheritance is something I think about a lot in my work and after reading this essay I have so much to think about. Thank you Melinda!

Annie Strader

Assistant Professor of Art

Sam Houston State University

Melinda. What a beautiful piece. I read it a few days ago, and it’s been following me around ever since. You bring to light something I realize has been haunting my own work, but that I haven’t quite been able to articulate. Much of my work as a critic, educator, and psychotherapist has been concerned with women and depression–otherwise known as mothers and daughters and depression. Or, actually, otherwise NOT known as mothers and daughters and depression, because in the land of psychological stats and pharmaceutical advertisements and neuroscience-obsessed psychiatry, women are women are women. Seen one, you’ve seen ’em all. Like mother, like daughter. But there’s actually something very particular about the ways depression shows up in the mother-daughter relationship that doesn’t get talked about much. As a critic, educator, psychotherapist, *and* daughter of a depressive mother, I’ve come to see depression (as both constructed and lived) as complicit in the same kind of disappearing act you so brilliantly identify: i.e., as a means of muting, or boxing, or blotting out, or extinguishing the “excesses” of our mothers, ourselves. Your piece has helped me see this disappearing act as part of a larger cultural phenomenon–and, sadly, a longer legacy of loss. Thanks so much for the insight and understanding, Melinda. I hope there’s more where this came from!

Melinda,

Your essay on hidden mothers made me think of the well known passage in Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge in which the narrator Malte talks about his “sister” Sophie:

“We remembered that there had been a time when Maman wished I had been a little girl and not the boy that I undeniably was. I had somehow guessed this, and the idea had occurred to me of sometimes knocking in the afternoon at Maman’s door. Then, when she asked who was there, I would delightedly answer ‘Sophie,’ making my voice so dainty that it tickled my throat. And when I entered (in the little, girlish house-dress that I wore anyway, with its sleeves rolled all the way up), I really was Sophie, Maman’s little Sophie, busy with her household chores, whose hair Maman had to braid, so that she wouldn’t be mistaken for that naughty Malte, if he should ever come back. This was not at all desirable; Maman was as pleased at his absence as Sophie was, and their conversations (which Sophie always carried on in the same high-pitched voice) consisted mainly in enumerating Malte’s misdeeds… ‘I wish I knew what has become of Sophie,’ Maman would suddenly say in the midst of these reminiscences. Of course Malte couldn’t give her any information about her. But when Maman suggested that she must certainly be dead, he would stubbornly contradict her and beg her not to believe that, however little he could prove it wasn’t true.”

It would be possible to read in this passage the mother’s desire for a daughter and a son’s desire for a sister, if only it didn’t end with Sophie being killed off. Malte and Maman reminisce about Sophie as a ghost, not as a game. Maman’s side of the family is associated with all kinds of uncanny, ghostly phenomena. To use some of your words: maternity in Rilke is a dynamic signifying presence, something unknown, that seems not to be there, or at least not to be there in any stable way. (This may be why Malte writes that he can only remember his mother’s family home as if it “had fallen into me from an infinite height and shattered upon my ground.”) The hidden mother is a dynamic mother, a figure that requires particular ways of reading.

Your essay makes me think that there might also be some kind of photographic background to another episode in Rilke’s novel, where Malte wants to tell Maman about a phantom hand he’s seen (and that seems similar to the hands in some of the images here). Malte stops himself from telling her about it because he’s “afraid of what Maman’s face would look like when it saw what I had seen.” But even if he keeps the story to himself, even if he realizes that life would be “full of truly strange experiences that are meant for one person alone and that can never be spoken,” he still has one person in mind as a potential addressee for his hidden tales: his mother.

Thanks for this essay – it’s given me a new set of images and concepts for thinking about mothers and the uncanny, and not only in Rilke’s strange book.

Patrick Greaney, University of Colorado

First of all, this is a great piece — an insightful reading with a poetic undercurrent. Very nice work.

I have greatly enjoyed reading all of the comments above, which tend to more personal reflections on our own mother/daughter relationships (and traumas).

I wonder about my grandmother in this “hidden mother” scenario, as she was a photographer’s assistant by trade. All of our family pictures were printed by her, and lovingly hand captioned for each of her eight children. She was very rarely present in the photograph, but rather behind the scenes, steadying the tripod. In this way, her presence, like the erased mother within the frame, is erased visually from our family archive. But somehow the tactile photographs are still a reminder of her presence and hover over the image, from somewhere beyond.

I think many of us have family albums that were compiled and captioned by mothers, and I wonder how this practice fits within your framework. Perhaps mothers construct a personal, visual history through these albums – one that is in opposition to the erasure and masking of popular culture and mythology. Or perhaps this further renders the mother as invisible support to the construction of one’s history and identity…

This article reminds me Hein Kuhn Oh’s photos, a Korean photographer who took middle aged women. The status of middle aged women in Korean society is quite unique and uncertain. As to their sexual identity, they are not considered male or female. They are regarded as in-between, forming a new type of “tribe” that presents a certain culture, attitude, and behavior. In the course of the rapid economic development after the Korean War, individuals sacrificed much for the reconstruction of the nation and family. Mothers sacrificed for their husbands and sons, giving up their own desire for achievement. Instead of femininity, they became armed with a strong backbone. Despite their sacrifices, in this harsh period they have not been fairly treated by either family or society, both of which are strongly dominated by patriarchy. Their sacrifice has been taken for granted, and the tendency to neglect this class of women has prevailed throughout the society. Tough, impolite, and stubborn are words typically used to describe them. Oh’s photographs expose these views toward them. Under a direct flash, the Ajumma portraits present middle-aged women in thick makeup who look tough and strong. Ajumma means “middle-aged women” in Korean.

http://www.heinkuhnoh.com

Keum Hyun Han

Visiting Assistant Professor Adjunct

Film Studies

University of Colorado at Boulder

I think you all read way too much into what was just a technical device. You see a woman being erased, I imagine a woman giggling behind the drapes, sharing jokes with the photographer and perhaps a friend who came with her. Can you not imagine bawdy jokes being exchanged, suggestions about what could go on behind the drapes?

I can’t help wondering if any of you know any real women. My mother was born in 1905, her mother in the 1860s, they had big personalities – as did most of the women I knew when growing up in the fifties. The picture that’s presented of ‘invisible women’ doesn’t gel with my experiences. OK, I grew up in Ireland and it was a different society, but human beings aren’t that different anywhere in the world.

If anything, I felt sorry for men, viewed them as a bit functionless, characterless, filling their lives with golf and fishing – hobbies, because they had nothing more interesting to do. I was SO thankful to have been born female.

Invisible my arse!

In the Article, “Who was that Masked Woman? Rediscovering the hidden mother”, Malinda Barlow explains the relationships between mothers and daughters portrayed in media such as television, movies, and photographs throughout the last 60 years. The article displays a picture, “The Happy Family #6” by Laura Shill. The picture shows a mother from the 50’s giving her daughter a bath and holding her face down into the water, drowning her, while cheerfully smiling the whole time. Perhaps it was the notion in the 1950’s that everything in one’s home life must appear perky and happy to outsiders, even when it isn’t, that prompts the smile on the mother’s face.

In any case, the article and this picture in particular brings to mind the relationship between “Skins” characters, Frankie, her mom, her two dads, and her sister. During the season finale of the sixth series, Frankie decides to find her mother who gave her up for adoption as a small child. Upon finding her old house, Frankie re-meets her older sister who refuses to answer any of Frankie’s questions about their mother out of anger. The sister eventually tells Frankie that their mother was a horrible person, always drunk, abusive, and unable to take care of herself or anybody else. She leads Frankie to believe that their mother committed suicide, which sends Frankie into a fit of hysteria.

Her lack of a mother-daughter relationship, even a crazy one as her mother had with the sister, left Frankie without any sense of what it is to have a mother and so she always felt like there is something lacking in her life. This leads Frankie to constantly run away, as she is always looking for something or someone to satisfy her but she is never satisfied.

We later find out that the sister lied and their mother is actually still alive and living in a mental hospital, which is the case for many of the crazed mothers from the article. Sort of like the mother smiling as she drowns her child, Frankie’s mother basically did the same thing by giving her up. She did what she thought was best at the time, even though she was hurting her children in the process.

New players may find the going tough to begin with only having the bare essentials, but Modern Warfare 2 makes it all worth your while. You can sell almost any item at a flea market if the price is right. To get you started, here are my suggestions on cook off themes, d.

First of all, this is a beautiful piece, it sheds light on the mother-daughter relationship that is frequently talked about, and providing a new perspective on the seemingly passive female role in the family (as well as in the society).

To me, the pictures with the “invisible” mother holding up her children are most striking, as these scenarios still happen nowadays in a society with much gender equality than decades ago. The reason, then, for mothers always being backstage cannot be solely attributed to gender inequality or the so-called passivity of women. In fact, when people are seeing females being erased from the these photos, it might also be a voluntary motherly move that those women have taken initiatives in. Mothers are never jeopardizing their mother-child relation. They literally put their children in the center, and are willing to hold their backs when they fall. Women are not necessarily oppressed or confined, in the contemporary society with a growing proportion of professional women, mothers are still doing what they did a hundred years ago. That is, saying that women have to sacrifice their life outside of the household in order to preserve the mother-child relation is presumptuous. Even in the case of the knife-throwing video, the mother would never hurt her daughters; the knife-throwing, with the girls posing happily, even professionally, for their mother, might even be a connection between them that is one of a kind; the successful completion of the stunt can even enhance their mother-daughter relation, instead of wounding it.

Pingback: Vuxis Blog

Pingback: Cream Blog

Pingback: Puzzle Blog