Direct Action Everyday: Adventures in Aesthetic Activism

Esteban del Rio / University of San Diego

Over the last quarters and semester, the “Arab Spring” cast a steady stream of news images across screens depicting dissent, demagoguery, and domination as protesters and authoritarian regimes fought for the balance of power. As early hope for widespread democratic change enveloped the events of Tunisia and Egypt, the slowly unfolding violence of Bahrain, Syria, and Libya reminds us that symbolic barbs and blows hold ugly material consequences. Nevertheless, the story of social networking emerged early, especially in U.S. coverage, as a key storyline of the popular uprisings. It was enough to make Malcolm Gladwell’s oft-cited New Yorker essay from 2010 appear passé. Gladwell argues that the weak ties of social networking prevent participants from engaging in high-risk activism . Even after Tunisia, Evgeny Morozov stated in Mother Jones that events “were driven by economic and political considerations (and internal politics, like the refusal of the army to intervene) than they were by the presence of social media.” But throughout the spring in the Arab street the images overwhelmed skepticism. Spawned by Facebook and Twitter, movements grew from thousands of people from all walks of life taking dramatic risks – even fighting off mounted camel attacks – in a televised fight for political power and national identity.

Not so long ago approached as a special topic in social change literature, the Internet has quickly become fused with more traditional public-sphere efforts in social change campaigns. But as demonstrated in the debates from this spring, networked activism continues to present a range of challenges and opportunities in democratic life for lone activists and advocacy groups alike. Lance Bennett argues that while networked activism produces ideologically thin ties, the fragmentary nature of such efforts allow for quick changes of strategy and an ability to rebuild quickly if a campaign doesn’t go well.1 Weak social ties and a precarious collective identity may render networks more nimble than traditional forms of organization, but they also present a challenge for building a sustained movement. Kristy Best suggests that networked activism creates a temporary articulation:

What is valid in networked activism is the extension of democratic experience to an array of practices aided by modes of communication (even though the value of these forms will be necessarily ambiguous) as well as the articulation of local voices and concerns around provisional forms of collective identity. What is worrisome is that the articulation that creates the means for collective identity also creates problems for the formation of a collective ‘‘we,’’ problems that may be exacerbated by a circularity and feedback between modes of representation and participation.2

The contingent and conjunctural nature of these networks, and the central role that representation plays in how they are articulated, brings two important issues to the forefront: the role of media and the depth and impact of political projects that flow through communication networks. Kevin Michael DeLuca and Jennifer Peeples’ notion of the public screen3 remains essential in understanding the intersection of these issues. Participation in the public screen requires subjects to create compelling visuals in order to exploit the professional bias of journalists and garner media coverage or to create DIY media as a form of direct action.4 Perhaps the prototypical public screen participant is the Fathers 4 Justice activist who in 2004 dressed as Batman and scaled a ledge at Buckingham Palace, making news around the world as he unfurled his banner raising awareness about the organization, which advocates for the rights of fathers in custody hearings.

Easily gleaned from this example, one of the key limitations of the public screen is that one must communicate by image, which mirrors some of the same issues raised by skeptics of the power of social media: that such strategies sacrifice depth for breadth. But working within the rubric of the shallow and the ideologically thin, a strategy emerges that may be particularly effective: aesthetic activism. Within the public screen, aesthetic activism uses images to charm people into social change. Relying on depictions of beauty, fun, and flavor, these appeals work as invitations to alter one’s everyday life in order to cultivate major reordering of social, political, and economic relations. Two sites of contestation serving as examples are food and transportation.

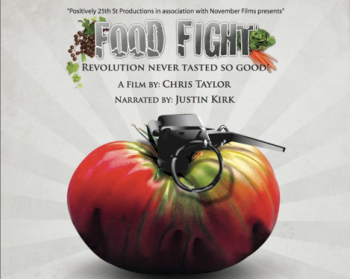

The food justice movement has considerable momentum, spurred along by the books of Michael Pollan and Eric Schlosser, Food Inc (2008), and the multitudes of local food activists developing an alternative to factory farming and supermarket retail. Media has been central to this project, from the major books and films to the social networking that facilitates community supported agriculture (CSAs) and community gardens. A consistent argument is made in these circles that one can cultivate large-scale change, as Food Inc. puts it in the closing credits, “three times a day.” By eating differently, the status-quo factory farm model will lose its hegemonic position and be replaced by something more sustainable, and perhaps local. Texts such as Food Inc. make a coherent, rational, and powerful argument for why this should happen. The film Food Fight (2008) seizes on one of the strands that often sits on the margins of the larger health and economic contests in this arena: flavor. The film looks a lot like Food Inc., but rather than developing a comprehensive thesis on the myriad implications of food justice, the film focuses on the savory nature of real food and features chefs like Alice Waters of Chez Panisse in Berkeley. Rather than dwelling on the potentially controversial issues of labor, environmental sustainability, immigration, and health policy, the central tenet of the film is features an aesthetic and relatively non-controversial appeal: change the food system because it will taste better.

A second example of aesthetic activism has to do with transportation and bicycle advocacy. Moving away from traditional public-sphere protests and appeals to government officials, utility cyclists around the world use blogs and social networking to post photographs that show the beauty and fun of riding a bicycle as an alternative to monotony and frustration of driving. But the social networking is not so much Facebook as it is Flickr. The photo-sharing site builds community around shared images and interests, rather than beginning with pre-constituted matrixes of acquaintances and other relations. This focus on the image fits neatly into the idea of aesthetic activism: photographs and groups emerge that aim to delight and inspire the viewer with depictions of the highly visual nature of bodies floating through spaces, featuring everything from the well-dressed riders of the Vélocouture and You look better on a bike groups to the flash of smiles that accompanies photographs of families riding together as seen in the group Kidbike!. These images, as in similar DIY films, slideshows, and blog entries, stand as a gentle invitation into an effort to change our relationships to petroleum, the internal-combustion motor, and the political status quo that supports both industries. And it does so through style and fun, much the same way that subcultures were written about 30 years ago, but with a political agenda and social change as the larger project.

Granted, these efforts pale in comparison to the immediacy and political depth of the revolutions and civil wars of the “Arab Spring,” as well as the debates that surround those still-unfolding events. Bicycles and food may not constitute politics with a capital “P” in such a way, but they do point to everyday choices that folks might make that necessarily lead to revolutionary change. The varied efforts to invite participants into revolution should not be easily dismissed. While potentially seen as vapid at first glance, aesthetic activism may provide a shallow but highly motivational summons for projects that have immense depth behind the shiny veneer. As Best argues, we must “engage much more directly with the specific forms of collective action that are implicated by diverse and diffuse forms of practice and display rather than assume their lack of validity as a consequence of their refusal to form a recognizable public sphere.”5 As networked activism matures and becomes more diverse and more persistent, scholars should continue to investigate the meanings and material consequences of contemporary social change, especially the ones that seem to be the most simple and enmeshed in everyday life.

Image Credits:

1. Critical Mass

2. Buckingham Batman

3. Food Fight

4. Bike Dad

Please feel free to comment.

- Bennett, W.L. (2003). Communicating global activism: Strengths and vulnerabilities of networked politics. Information, Communication & Society 6 (2). 143-168. [↩]

- Best, K. (2005). Rethinking the globalization movement: Toward a cultural theory of contemporary democracy and communication. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 2 (3), p. 231. [↩]

- DeLuca, K. M. & Peeples, J. (2002). From public sphere to public screen: Democracy, activism, and the “violence” of Seattle. Critical Studies in Media Communication 19 (2), 125-151. [↩]

- del Río, E. (2010). Pedaling through the Transnational Public Screen. Flow 12 (2). Available online: http://flowjournal.org/2010/06/pedaling-through-the-transnational-public-screen/ [↩]

- Best (2005), p. 232. [↩]

This is a really interesting article. I think a lot of activists/sm nowadays knows that design and aesthetics have become super important to grasp the attention of Internet and social media users that are glancing at a ton of information.

However, I wonder how useful these moves really are or can be. Both the food and bike movements have been heavily criticized for their classism, racism and assumed white, middle-class subject and audience and I would say that the image they have projected through this “aesthetic activism” has exacerbated that.

Moreover, this kind of activism seems to affect more the personal/individual side of these problems rather than the global/governmental/industry level. For example, this activism urges individuals to ride bikes, but does it urge them to fight for renewable energy sources, to ask for taxes for environmentally unfriendly corporations (or whatever)?

Excellent point, JF. My experience with the Austin cycling community has been extremely inspiring as far as sheer numbers go — any given thursday night, the most popular night for social rides, there will be anywhere from 200-500+ cyclists on the road — but you’re right, there isn’t much emphasis placed on sustainability. However, the activism in Austin (again, I’m specifically referring to the cycling community) is currently focusing on road safety. In the past three weeks, at least two cyclists have been hit by cars due to driver negligence. One cyclist died at the scene, and the second is in recovery after sustaining a head injury. There are probably more unreported instances of vehicular contact with cyclists, but there’s also an extremely high level of harassment from motorists. The cycling community, in response to the environment, is trying to foster a more bike-friendly experience with drivers (ride AS traffic, not against), and perhaps in getting more butts on bikes, there is an implicit endorsement of alternative energy and environmental causes. After all, one more bike means one less car. While i do personally believe that there should be more emphasis placed on renewable energy or other environmental issues, I also believe that road safety is the number one priority for urban cyclists.

Great article, as always. It took me a very (very!) long time to admit the importance of aesthetics in advocacy, and I do believe you contributed a great deal to the narrative I have chosen to accept even if it took me a long time to even understand it. To a large degree my discomfort with aesthetics did have a lot to do with my own idiosyncratic views on everything along with my own body image issues, but by knowing that my contributions are only a speck in the larger movement…I was comforted and was able to contribute a little tiny bit.

I think this was by far my favorite part in the essay, “Bicycles and food may not constitute politics with a capital “P” in such a way, but they do point to everyday choices that folks might make that necessarily lead to revolutionary change. “