Museums, Social Media and the Possibility of Canonizing Online Life

Konrad Ng / University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

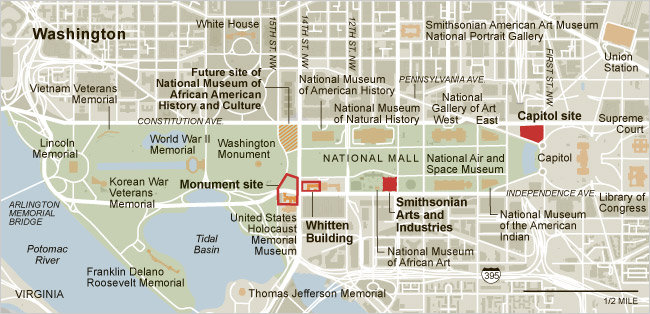

The New York Times recently published an article on the National Museum of the American Latino, a project to create a new Smithsonian Institution museum for American Latino contributions to the U.S. Following the creations of the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall, reporter Kate Taylor writes that even with congressional support, the National Museum of the American Latino continues to face political and financial pressures “and a feeling among some in Washington that the Smithsonian should stop spinning off new specialty museums and concentrate on improving the ones it already has.” The topic continued in The New York Times “Room for Debate” where university and museum voices expressed support for the project by citing its capacity to tell the American story in diverse terms and be relevant to contemporary American life. What does the experience of the National Museum of the American Latino and the current political, economic and cultural climate say about the future of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities, histories and cultures and their place on the National Mall? In a special journal issue on AAPI art and cultural institutions, editors Franklin Odo and Paul Ong contend that the longtime obscuration of the AAPI experience from entrenched stereotypes in the American imaginary has meant that institutions like museums, libraries and historical societies have become “the default targets to secure more accurate representation, or even representation at all[;]…[t]hese institutions have become, in short, serious sites of contestation—among the latest battlegrounds in the American culture wars.”1 Yet, given the journey of National Museum of the American Latino so far, how might the canonization of AAPIs take form?

Perhaps, one possible answer can be gleaned from a The New York Times special section on the intersection of social media, technology, the Internet and museums. This section published articles that explored how museums were using technology to increase public engagement and transform the role of art institutions and their relationship with the public. In “The Spirit of Sharing,” Carol Vogel writes that social media is turning museums “into virtual community centers. On Facebook or Twitter or almost any museum Web site, everyone has a voice, and a vote. Curators and online visitors can communicate, learning from one another. As visitors bring their hand-held devices to visits, the potential for interactivity only intensifies.” Another article, “Smithsonian Uses Social Media to Expand Its Mission,” reveals how crowd-sourcing and user-generated content are becoming common tools in expanding the mission of the 164-year-old organization to “increase and diffuse knowledge.” While the thread that runs throughout the articles details how social media is becoming a common element of museum practice, the intersection of social media, technology, the Internet and museums opens interesting possibilities for redefining, documenting and diversifying American life. The concept I want to mine is not how social media recruits and channels American life into offline spaces like museums, rather how social media produces forms of American life native to the online world. These forms of cultural production, I argue, expand the meaning of “life” and they suggest how we may canonize the AAPI experience in terms that are not tied to “brick and mortar” spaces.

In Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet, Lisa Nakamura reviews the relationship between race and the Internet and contends that users of color are generally treated as the “interacted” in an intrinsically interactive medium; that is, they are studied as passive consumers of the Internet and race is conflated with online access and overcoming the digital divide to become unencumbered users. Such a focus, Nakamura claims, neglects how users of color are “interactors” or active producers of Internet culture that participate in the politics of representation and social change. She writes that most studies of Asian Americans and the internet tend to focus on “what types of services and activities they engage in, rather than asking them about their cultural production, such as postings to bulletin boards or creation of Web sites or other forms of Internet textuality or graphical expression.”2 These online popular cultural productions prompt a

reenvisioning of what constitutes a ‘major life activity’[;]…In the case of people of color, popular culture practices constitute a discursive domain where they are more likely to see cultural producers who resemble them; and most importantly, these are exactly the spaces that invite participation by users. This is important information in the context of Internet users and their lived realities.3

Nakamura’s argument suggests that racial groups like Asian Americans produce online cultures that that are as compelling and important as life in the offline world; the idea is that online life are edifying elements of the American experience. Let me offer a preliminary sketch of the kind of online cultural production that leads to such a novel heritage.

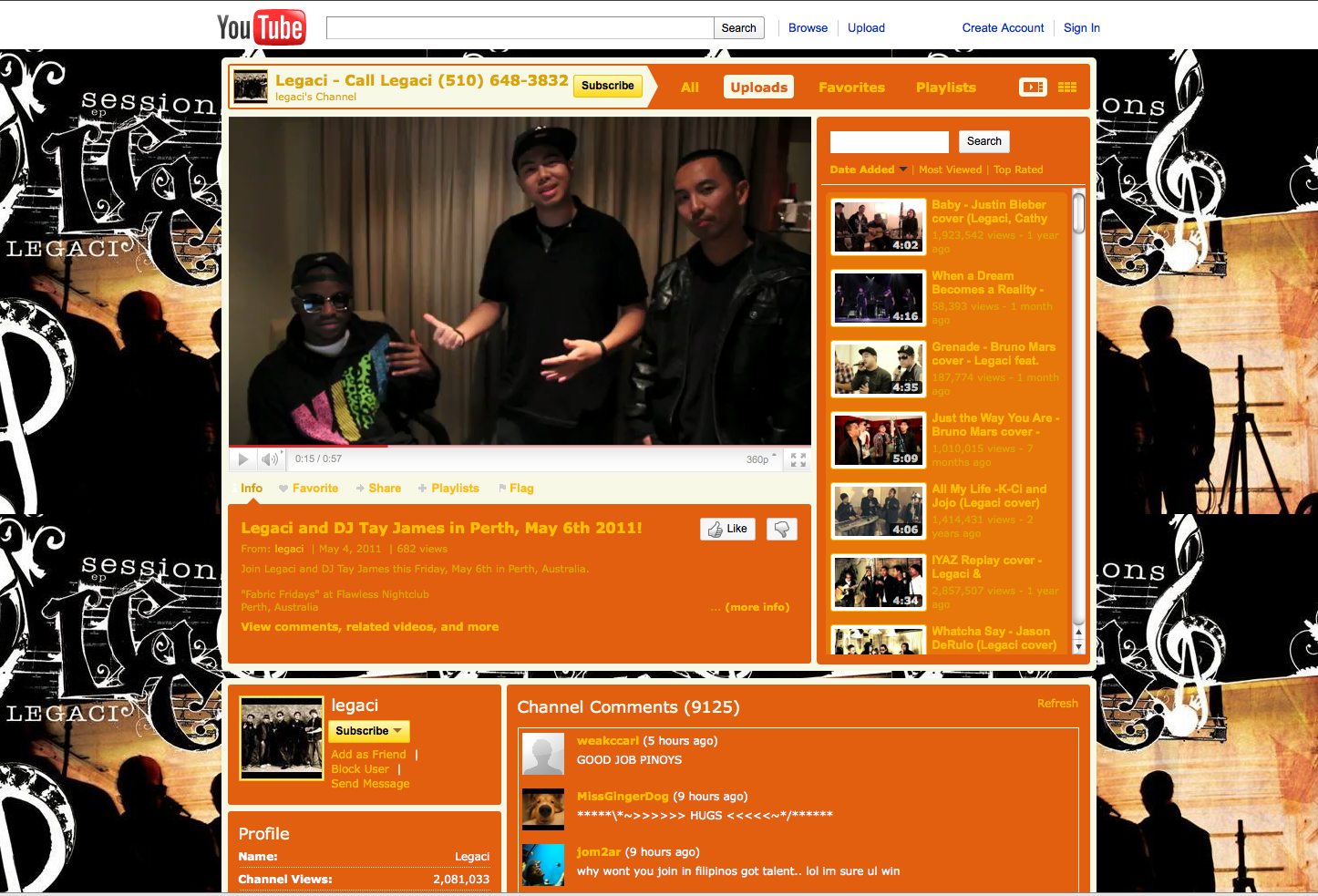

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jcUdeN1uBWQ[/youtube]

Legaci, four Filipino-American R&B singers from San Francisco who rose from local success to worldwide exposure, credited part of their rise to YouTube. The band created a YouTube channel to post videos and cultivate a fan base. One performance, a cover of popular star Justin Bieber’s song, “Baby,” went viral and caught the attention of Bieber’s manager who then hired them. In “Unexpected Harmony,” The New York Times reporter Josh Kun writes:

Before joining Mr. Bieber’s touring group, they were rising stars on YouTube, now a crucial launching pad for Asian-American artists seeking the kind of exposure rarely afforded them by the mainstream recording industry[;]…the one place where Asian-American artists flourish in contemporary pop is on YouTube.

Kun contends that the online platform of YouTube allows Asian American performers to pursue alternate routes to public exhibition and by so doing, challenge the stereotypes and conventions that have handicapped Asian Americans in the entertainment industry. Legaci’s professional ascent is noteworthy for how it illustrates the way YouTube has become a major life activity for Asian America. The unique properties of this online lifeworld are illustrated by how Legaci’s style and standing resonates with YouTube’s intrinsic online properties: an amateur/do-it-yourself (DIY) aesthetic. Kun writes, “singing somebody else’s songs in your bedroom or living room — had long been part of Legaci’s own upbringing. Its members all grew up singing pop and R&B hits on the karaoke machines of their Philippines-born parents.” The idea is that Legaci videos express a material reality that is native to the YouTube DIY platform and fleshes out the lived experience of Asian America. Put differently, the low production values of their DIY self-aware documentation of covering American music is a combination of aesthetic forces native to YouTube and produces an instructive moment in the representation of the Asian American experience; the layers of Asian America include music, immigration, identity, technology, race relations, popular culture and U.S.-Asia relations.

Given the challenges that face the creation of the National Museum of the American Latino, the “more accurate representation or even representation at all” of AAPI life may be tied to the premise that life will be increasingly produced online and the online world is increasingly central to life. As Nakamura observes,

[t]he wars over the Internet’s visual culture are taking place in settings that include the living room, but also extend outward in ways that other media have not. The Internet intervenes in people’s daily lives across social sphere and public spaces such as public libraries, cybercafés, and school classrooms and across platforms like the cell phone, the PDA, and the television.4

How we may canonize AAPI life in a national museum is far from clear but the journey may call for a path that is online. Here I see the creative spirit of Gilles Deleuze’s notion of “minor literature” where the power of the minor draws from the inflection of majoritarian discourses in order to take “flight along creative lines of escape.”5

Image Credits:

1. Legaci performs with Justin Bieber.

2. Author’s screen capture.

3. Author’s screen capture.

Please feel free to comment.

- Franklin Odo and Paul Ong, “Art & Cultural Institutions and AAPI Communities,” AAPI NEXUS (Vol. 5, No. 1 Spring 2007), v. [↩]

- Lisa Nakamura, Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 172. [↩]

- Ibid. 182-183. [↩]

- Ibid. 178. [↩]

- Gilles Deleuze, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Trans. Dana Polan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 26-27. [↩]

You have done a excellent work with this online informational web post.This is the kind of platform where windows 10 users comes to know how to connect or activate remote facility with their desktop.