The Gathering of the Juggalos and the Peculiar Sanctity of Fandom

Michael Dwyer / Arcadia University

Valuable work in the fields of media and cultural studies in the last thirty years has worked to reconsider the figure of the fan, rejecting reductive notions of fans as ideological dupes of the culture industry, or pathological figures of excess. The work of scholars in media studies from Stuart Hall and John Fiske to Henry Jenkins and Sarah Thornton, among many others, have shown us the way that fan practices can work to resist corporate domination, to subvert patriarchy, or to reveal potential for democratic activism. Fans have gone from pathetic and pathological to academic cause celebre. In this essay, however, I would like to sound a discordant note—not because I do not believe in the value of Aca-Fandom, but rather because I believe Aca-Fandom requires a critical self-reflexivity, particularly about the nature of “fandom” itself. To begin, I want to discuss a particularly dramatic case of fans engaging in “participatory culture,” a case that deserves no celebration.

Last August, the eleventh Gathering of the Juggalos was held in Cave-in-Rock, Illinois. Psychopathic Records, the independent hip-hop label co-founded by the rap duo Insane Clown Posse, organizes the annual Gathering annually, drawing legions of fans (called “Juggalos” and “Juggalettes”) from across the nation. For the past decade Gatherings have featured performances by musicians (mostly from the genres of rap, rock, and rap-rock), stand-up comedians, and professional wrestlers, not to mention carnival rides, games and contests, and late-night parties hosted by prominent members of the Psychopathic Records family.

It was at one of these late-night parties this past August that the Gathering met the national media spotlight. On August 13, the Gathering had their first “Ladies’ Night” event, hosted by Psycopathic Records personality Sugar Slam and headlined by rap superstar Lil’Kim. Also scheduled to perform was model and reality TV personality Tila Tequila, who was there to promote her latest dance/hip-hop EP. As soon as Tequila hit the stage, however, she was met with a torrent of rocks, bottles, refuse, rotten food, firecrackers and human waste. One fan attempted to rush the stage, while another was subdued before he was able to toss a large trash barrel towards the performer. When security escorted Tequila offstage with multiple injuries, members of the audience pursued her, surrounding her trailer until police arrived on the scene.1

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XviWmGTa6M[/youtube]

These actions can be legally in the realm of assault, of course. However, for the purpose of this essay, I would like to think about these practices as an important part of Juggalo fandom. This event, after all, is not without historical antecedent. At the Third Gathering of the Juggalos, Southern rapper Bubba Sparxxx was unceremoniously run off the stage and fans at subsequent Gatherings have unofficially bestowed “the Bubba Sparxxx award” to performers deemed to be too “mainstream,” or “not down with the clown.”2 Taken together with face painting, carnival games, amateur wrestling and open mic competitions, fan violence is part of the “participatory culture” of the Gathering. Inverting the conventional relationship between fan and audience, Juggalos at the Gathering shower performers with hatred, and see who can prove their worth by withstanding the assault.

Even though Tequila, with her self-promotional use of MySpace and MTV-fueled celebrity has been described as “everything [the Juggalos] hate”, her performance was one of the most hotly anticipated events at the festival.3 This is not because Juggalos were particularly interested in her music or her performance, but rather because fans were anxious to witness, and in some cases participate in, fan violence. Weeks before the Gathering opened, Juggalos posted messages on Tequila’s blog like “i fucking hate you and i will teach you not to come back to the gathering,” “ima b the one who pegs that mainstream bitch,” and “k u faggot ass fuckers i hope tila ass gets knocked out dragged in the wods and beat to a blood pulp … this is a time for juggalos not stupid lil preppy bitches and dick rideing homos.”4 When Tequila finally took the stage, the misogyny reflected in the blog comments was revealed as a concerted strategy of organized and pre-planned fan response to Tequila’s performance. As a steady chant of “SHOW YOUR TITS” rang out, fans revealed a banner reading “CUNT,” while others hurled dildos and other sex toys to accompany the aforementioned rocks, bottles, and human excrement directed toward Tequila and her bodyguards. It is crucial, I believe, to reiterate this point: these practices are fan practices, and are integralto the pleasures enjoyed by many of the festival attendees. While it is true that many ICP fans did condemn these actions (prompting a compelling series of YouTube vlogs of online Juggalos reflecting on violence against women), still others emerged to celebrate the actions as “awesome,” and insist that Tequila’s injuries were fabricated.5

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2zAdAey9XLI[/youtube]

The fact that some fan practices are repugnant is not, I am certain, news to anyone. Yet, there has been a peculiar framing of fan practices as inherently admirable, or at least deserving of respect, throughout recent scholarship on fandom. In a blog entry introducing the pre-publication version of “On Dislking Mad Men”, Jason Mittell prefaces the text by saying, “I tied myself in knots trying to avoid letting my dislike for the show come across as a disdain or judgment of its fans – I hope that anyone commenting here aims for the same respect toward those whose taste differs from yours.”6 In the essay itself, Mittell goes to great lengths to assure his readers that he is not in any way attempting to disrupt fans’ pleasure, or implicate them in his critique of the show. What I find interesting to me about Mittell’s disclaimer is the degree to which he views others’ fandom as delicate and precious, not to be disturbed by the dissenting voice. Just a few weeks prior, Jonathan Gray published a blog post regarding the finale of Lost titled “Don’t Picket the Funeral,” in which he wishes that those critical of the finale would, out of respect, allow for “a short mourning period for fans of a show once it’s over.” 7 The implication, of course, is that a show’s finale is akin to the death of a loved one, and that, in polite society, one does not speak ill of the dead. In pointing to these moments, it is not my intention to single out these essays, or these authors, for critique (I admire and respect the work of both Gray and Mittell, and their scholarly treatments of fandom are nuanced and sophisticated). Rather, I want to draw attention to the way that, in these specific moments, these authors position fandom as a concept that must inherently be respected and revered. In the long tradition of media studies, it would seem, fandom has gone from the profane to the sacred.

Henry Jenkins’ notion of the “Aca-Fan” has been vital in helping media studies bridge a mythical divide between our affective and intellectual engagements with texts. In his comment-debate with Ian Bogost, Jenkins argued that aca-fandom provided a methodology “which acknowledges and explores our emotional connections to popular culture and the way it functions as a resource in our everyday life.”8 The call for honestly and self-reflexivity, I’d like to argue, is profoundly needed in media scholars’ engagement with the status of fandom itself. That is to say, as academics and as fans, we ought to seriously interrogate our investment in the social, political, and cultural potential in “fandom,” and recognize that we ourselves are predisposed to believe that empassioned engagement with cultural texts is valuable, laudable, and politically useful. As the the violent and misogynist attendees of the Gathering remind us, it ain’t necessarily so.

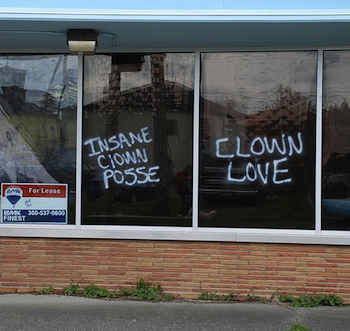

Image Credits:

1. Driven by Boredom

2. Norhwest Gangs

Please feel free to comment.

- “Tila Tequila Attacked at Rowdy Concert,” TMZ, August 14, 2010, http://www.tmz.com/2010/08/14/tila-tequila-attack-juggalos-concert-photos/. [↩]

- Kurupt, The Yin Yang Twins, Andrew W.K. and Method Man are among the many artists to have “Bubba Sparxxx” experiences at the Gathering. [↩]

- Nate Smith, “Dear Vice: I got Stoned by the Juggalos,” Vice, August 18, 2010, http://www.viceland.com/blogs/en/2010/08/18/dear-vice-i-got-stoned-by-the-juggalos/. [↩]

- Comments retrieved from: Tila Tequila, “MISS TILA PERFORMING AT 11TH ANNUAL JUGGALOS FESTIVAL,” MissTilaOMG!, July 24, 2010, http://misstilaomg.com/2010/07/24/miss-tila-performing-at-11th-annual-juggalos-festival-alongside-lil-kim-and-many-more/. [↩]

- Witness this YouTube Vlog entry from the charmingly-named YouTube user “rapeandkillpeople”, if your sense of human decency can stand it: TILA TEQUILA GOT HER ASS HANDED TO HER AT THE GOTJ. WHOOP WHOOP!, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C7BYFU-TFLw [↩]

- Jason Mittell, “On Disliking Mad Men,” Just TV, July 29, 2010, http://justtv.wordpress.com/2010/07/29/on-disliking-mad-men/. [↩]

- Jonathan Gray, “Don’t Picket the Funeral: The Lost Finale and its Anti-Fans.,” The Extratextuals, May 24, 2010, http://www.extratextual.tv/2010/05/don%E2%80%99t-picket-the-funeral-the-lost-finale-and-its-anti-fans/ [↩]

- Henry Jenkins, “Comment #59646 RE: Ian Bogost – Against Aca-Fandom,” Bogost.com, July 31, 2010, http://www.bogost.com/blog/against_aca-fandom.shtml#comment-59646. [↩]

“Bad” fandom practices is definitely an aspect of fandom that fandom studies seems to be unaware of, or that actively ignores. One of the only times I can remember them even being discussed was a fairly recent interview that Henry Jenkins did with Jonathan McIntosh (http://henryjenkins.org/2010/1.....mix_1.html), where there were a few lines mentioned about them by McIntosh at the very end of the interview, and didn’t go any further than “Vidding that doesn’t have progressive politics is bad”. I would be very curious about more explanations about “bad” fandom, what makes fandom “bad” fandom, the politics involved in “bad” fandom, etc.

Using McIntosh’s examples, is there a difference between 4chan making mashup videos that sexualize the Lucky Town girl and say, fan artists or fanfiction writers making pictures/stories about Snape raping an 11 year old Harry? Are they both “bad”/equally “bad”, etc. What about Twilight fans that share the political values of Twilight and make fanworks that celebrate those values? Are those “worse” than fans that make videos about how Buffy could kick Edward’s ass? They’re both passionate about their works, but one of them is anything but resistant or subversive towards cultural hegemony. How about the difference between anime fans that facilitate widespread piracy because they want to make people aware of shows that they really really like and (incorrectly) think that this will lead to higher sales for the “creators”, versus ones doing more or less the same act but for purposes of wilfully antagonizing the IP owners?

I wanted to be among the first to post because wanted to make sure one thing was clear. I don’t think what I’m saying in this piece is anything new, really, or anything that any media critic does not already realize on their own. I do think, however, that we do ourselves (as scholars and as fans) a disservice if we don’t periodically remind ourselves to not take the value of *any* practice for granted. I hope that was clear in the essay!

Oh, that comment came across as a terse response to jpmeyer’s. I hadn’t even seen that until now!

Fan violence is a topic of significant importance to those of us interested in understanding audiences. I appreciated this piece, Michael, because of the way you shed light on the choices that scholars of fandom make about what to pay attention to and what to ignore.

By calling attention to the omission, you invite scholars to reflect on their own ideological and epistemological positions re the full complexity of audience behavior. That’s important because the topic of fan violence addresses a peculiar challenge to scholars because of longstanding tensions between the cultural studies and media effects traditions.

To make sense of fan violence, it might be important to understand the role of various psychological mechanisms associated with aggressive behavior, including frustration and disinhibition. Have aca-fans examined sports fan violence? I’m not certain, but I don’t think so. Yet there are many good reasons why this topic is worthy of some close examination by cultural studies scholars. Acknowledging the ideological blinkers of aca-fandom and its solipsistic epistemology is important in identifying how these factors may limit the development of new knowledge in the field of audience studies.

I really liked this article, Michael, and in the interest of honesty and self-reflexivity wondered what personal investment(if any) you have towards ICP/Juggalos/Tila Tequila?

I only ask because I think – as you quite rightly state – “bad” fan practices need to be addressed, but approaches to discussing them seem to hinge on the author’s own relationship to the fandoms at hand.

For example, a scholar-fan approach to the Gathering may amount to a form of fannish defence of the actions (something I’m all too familiar with!), which acts as a distancing method by saying “I’m aware my fellow fans act in this manner, but I know it’s bad and I (and many others) are not like that.” In contrast, a non scholar-fan approach can frame the article as one of firm condemnation of the actions, but in doing so may be picking an “easy target”. That is to say, isn’t it probably safer to highlight “bad” fandoms separate from one’s own rather than admit to belonging to a group where such badness can occur?

Thanks to all for the comments. Forgive me if the following is a touch scattered, as I am feverishly trying to finish my grading for the semester.

I find myself resistant to using the terminology of “bad fandom,” here, as that terminology would presume that there is “good fandom” against which such practices can be understood, as well as identify this as a fandom problem rather than a misogynist practice problem. To me, fandom isn’t good, bad, positive or negative–it is a condition around which practices are initiated, and I think we ought to give more attention to the practices themselves rather than the organizing label.

I think much of the reason scholars do focus on the liberatory potential of fandom is that, as people who have dedicated our lives to cultural texts, we believe that our interaction with those texts has enriched our existence and challenged us to question our political and social assumptions–this is understandable. But, in my view, it is also our responsibility to question our own assumptions, and not let our enthusiasm and excitement over the potentials of fandom divert our attention entirely from a existing material practices that do not match our own lovely experiences with active engagement with cultural texts.

I do not have any particular affective investment in ICP or Tila Tequila, though I would consider myself an advocate of DIY music and cultural production, and both ICP and Tequila could be considered rousing successes in that regard. With that said, I would hope that my personal commitments to anti-racism, anti-sexism, etc would trump any investment I might have in a band, sports team, filmmaker or whatever (hear that, Pittsburgh Steeler fans?). Please don’t take this as a high and mighty response to your question–I think it is probably a mark of the privileged position we in media studies afford to fandom that it is even conceivable that it would be “safer” to compromise our political commitments than it would be to compromise our fan commitments. I would hope, both in politics and in entertainment, that our personal feelings for the actor would not *entirely* impede us in our reckoning of the action, though of course total objectivity is a fantasy. I would also hope, in my call for critical self-reflexivity, that we would actively resist the temptation to excuse ourselves from our own participation in systems of oppression. This, it occurs to me, is another reason I would hesitate to use the language of “bad fandom”–because it would allow us to draw a line with ourselves as “good fans” on one side and those “bad fans” over there, and free us from implicating ourselves as participants in communities that are simultaneously wondrous and repugnant, creative and destructive, good and bad, etc etc etc.

I’m not sure if there has been much investigation into sports violence. There has been a flurry of discussion about the fascist (literally, fascist) and racist practices of Italian soccer supporters (of which I would definitely recommend this example), as well as the discussion of misogyny & racism in FIFA in the blog From a Left Wing. I imagine there has been some sociology of “championship mobs,” but I’m not certain. Dougie Brimson’s book about soccer hooligans is the touchstone everyone refers to w/r/t fan violence, but I’ve not read it and I’m not certain how useful it would be in scholarship.

Thanks again, and apologies for the hurriedness of the response. Back to the grading mountain I trudge!

Pingback: Daily Links from the Selectism Staff | Selectism.com

Pingback: Selectism | Around the Web | Purple Kush Kisses

Pingback: Juggalo jenkins | Naimafaddin

I think it’s really important, as scholars attempt to grapple with the ever-evolving practices of fandom to take into account the violent, abusive or destructive behaviors that can go hand in hand with fan practices. I recently used Mark Andrejevic’s article “Watching Television Without Pity: The Productivity of Online Fans” using concepts of fan labor and the product of such labor as a point of entry for talking about fan practice. Because work goes into these behaviors, but to what end?

But the labor and work that goes into something that is destructive and violent (not that that is anything NEW in society, but in the service of fandom, something inherently positive, ie. “I like and support this entity as a fan”) troubles the question of the product of this fan labor. The organization and online communication in order to hurt and humiliate, which is in order to demonstrate a commitment to fandom, demonstrates the amount of work, and without calling it “bad,” but acknowledging that the labor was in service of violence and degradation makes it hard to celebrate what the product of this labor is.

Much fan labor translates into a product of cultural capital (as laid out by Bourdieu), which offers a certain regard or standing within a fan group, and I can see how the violence of the Juggalos would serve as a performance that signifies to the other fans, “this is how hardcore I am, are you?” This intense fandom (of a group that glorifies and celebrates violence within its text) plus the mob mentality that can be found at music festivals such as this (Woodstock ‘99 anyone?) ignites to create an explosion of destructive energy and chaos as an expression of fan practice. It may translate into cultural capital within that group, but I don’t think that it will be able to translate into a social capital that can be made tangible. In fact, I think this kind of cultural capital may have the reverse effect of translating into positive social capital. But maybe that’s what the Juggalos’ intentions were. It’s a fan labor that works overtime to keep outsiders out for fear of destruction. So maybe their fan labor was successful after all.