Special Issue: Revisiting Aca-Fandom

Is Aca-Fandom still a useful theoretical trope? Does it privilege some objects and remove the possibility of discussing others? Do we, as scholars have an obligation to reveal our positions, likes and dislikes, or are we expected to be better than that? Put differently, is aca-fandom merely a way to justify and privilege some tastes and thus reinforce them?

In the past six months, aca-fandom related posts have ranged across academic blogs, and are indicative of the current and ongoing investment in the topic. Though one could say that it was a long time coming, the most recent debate was provoked by Jason Mittell’s online piece “On Disliking Mad Men”. Related posts moved between several sites, including Ian Bogost’s “Against Aca-Fandom”, Katrina Busse’s “Geek Hierarchies, Boundary Policing and the Good-Fan/Bad Fan Dichotomy,” Henry Jenkins’ “On Mad Men, Aca-Fandom, and the Goals of Cultural Criticism” and to some degree, Heather Hendershot’s “On Stan Lee/Leonard Nimoy and Coitus: or, the Fleeting Pleasures of Televisual Nerdom” were only part of this flurry of new works, that used aca-fandom as their starting point. All of this action speaks volumes about the unsettled nature of aca-fandom today and the desire to keep the debate alive.

Conceived by scholars as a means to legitimate their immersion in their subject matter, aca-fandom was an effort to position the author within the center of the debate and to elevate different tastes within the field of media studies. Henry Jenkins, Tara McPherson and Jane Shuttac published the anthology, Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture, in hopes of steering cultural studies towards the personal within mass culture. Their “Manifesto for a New Cultural Studies” was a call for realignment in order to reposition the scholar within the field as someone who was “interested in the everyday, the intimate, the immediate.” Above all, they rejected “the monumentalism of canon formation and the distant authority of traditional academic writing”1. Recognition of fandom within the academy would eradicate the paradox of attempting to write “about popular culture from a distance” and thus distinguish “popular from the bourgeois aesthetic” which was often reified in universities2.

Over a decade later, major questions remain about aca-fandom. In the meantime, what has happened to the original issues of identity and politics that fandom used to represent? Is it possible that our efforts to widen the spectrum of debate has merely reduced the field down to several privileged objects? In the television arena, this generally means discussing issues of quality over mass, subtly reinforcing our preferences for TV auteurs and their wares as the usual suspects, regardless of their ratings or their appeal in the larger media landscape. Aca-fandom favors the nerdy, the hip, the savvy (and at times the crappy) but rarely does it privilege the middle, leaving a wide range of ground to be covered as well as a great deal of material that never gets discussed at all.

Into the fray moves Flow, with our current special issue, “Revisiting Aca-Fandom.” Our contributors are wide-ranging and we believe our selections reflect new and important provocations for the continuing and (we hope) robust debate to come. Eve Ng’s “Telling Tastes” speaks about the institutionalization of aca-fandom within the conference community, while David Jenemann’s “Stop Being an Elitist, and Start Being an Elitist” charges that without a discussion of sports fans, the project of aca-fandom is doomed to failure. In different ways, Coker & Benefiel’s “We Have Met the Fans and They Are Us,” Dwyer’s “Gathering of the Juggalos” re-center the scholar’s personal tastes within participatory culture, shaping the larger discourse. Booth’s “Fandom as/is the Academy” puts fandom into and even larger historical shape, whereas Phillips’ “Embracing the Overly Confessional” sets up a schema for his own investment in Kevin Smith’s work. We are particularly proud to highlight oft-neglected considerations of international fandom here, such as Tchouaffe’s “Revisiting Fandom in Africa.” Gunnels and Klink add a performance studies perspective to the notion of fan studies and its ethnographic component in “We Are All Together: Fan Studies and Performance.”

As always, the editors of Flow hope that this issue provides a forum to discuss, question and debate the topic and as we continue to question our role within media and cultural studies.

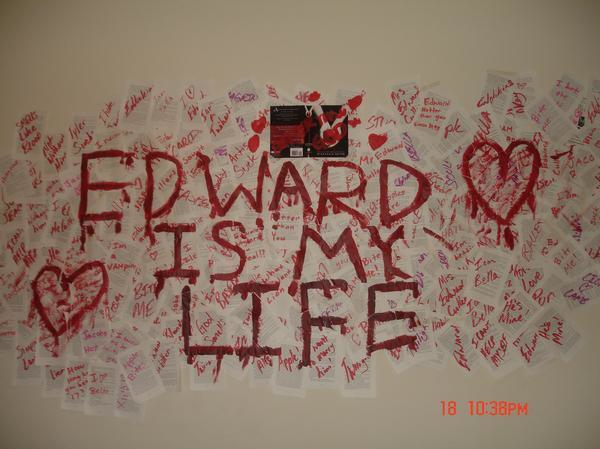

Image Credit:

1. Fanpop

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Flow Publication | Confessions of a PeepingTom: Kevin Smith Fandom and Online Community

Pingback: SCMS 2011 Workshop: Acafandom and the Future of Fan Studies « transmedia