Kitchen Monoliths: Memories of Domestic Minimalism

Paul Gansky / FLOW Staff

There are times, I admit, when I have wanted nothing more than to inhabit a marvelously cold, clean kitchen filled with appliances resembling the Twentieth Century Limited – the kind of products championed by industrial designers Norman Bel Geddes, Raymond Loewy or Walter Dorwin Teague.

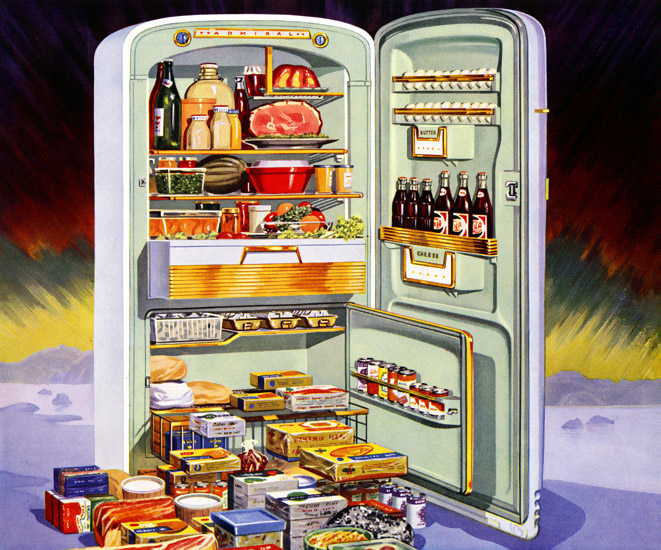

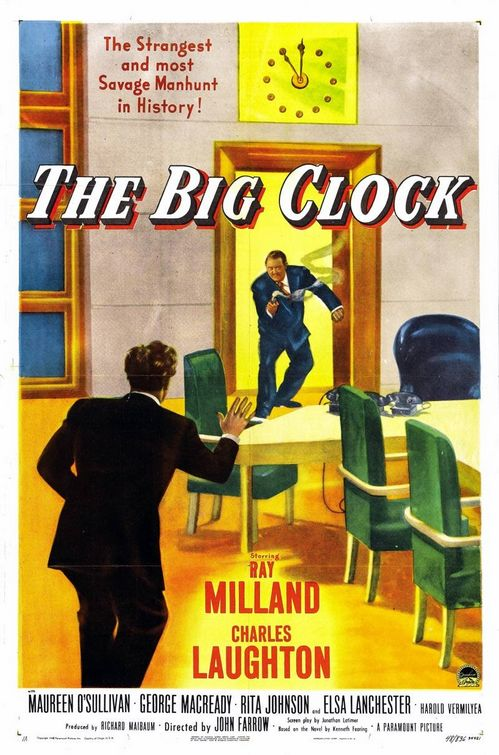

Given that my current tax bracket does not allow me to refashion my humble abode into a tiny wonderland of sheer enameled metal, I am forced to rely upon certain films and television programs that allow for extended time with these items and spaces. The classic noir The Big Clock (1948), for instance, is a ninety-five minute tour of silvery curves and rigorously functional design. One exemplary scene consists of actor Ray Milland simply walking past a Coldspot refrigerator, rounded and white and stripped of chrome. I find myself transfixed as Milland’s shadow skitters across the fridge’s surface. The scene is brief – a single shot lasting perhaps four seconds – but the play of light and deep shadow is palpable, the tactility of the fridge immediately apparent and reactive. It is background come suddenly to foreground. I watch The Big Clock and I wonder how it might have been to encounter this refrigerator from the vantage of 1948, freshly stamped from an assembly line in Milwaukee or Detroit. What would it feel like to see the door open effortlessly under one’s hand, revealing a chilled diorama of produce? Would I marvel at its Martian shape, like a cowed visitor to MOMA’s “Machine Art” exhibit that turned everyday appliances into sculpture?1 Or would I have found something repellent about this refrigerator’s relentlessly highbrow and sterile nature, attempting to wriggle into my home and teach me “taste”?

There are several films and television programs that deal much more prominently with industrial design, and I am especially interested in those that attempt to retrospectively imagine whether the construction of these objects did indeed eliminate the social “friction[s]” of everyday life.2 A prime example would be The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio (2005), taken from a popular memoir by Terry “Tuff” Ryan. The film is far from perfect, including an unhinged Woody Harrelson bent on perfecting his psycho-yokel persona that began with Natural Born Killers (1994). Nevertheless, the seed of this film – a plucky 1950s housewife (Julianne Moore) who keeps her family from dissolution by scoring big on contests that pay off in appliances – provides fertile ground for examining the relationship between the commodities that cascaded into many suburban homes in the 1950s, and the working and lower-middle class families that adjusted to their presence. As Shelley Nickles has convincingly argued, the marriage between the “good design” of these modern instruments and their users entailed a painful redefinition of class and ethnic identities.3 The Prize Winner dutifully enacts this intersection between family socioeconomics, kitchen space, and the introduction of a massive “Deep Freeze” Frigidaire freezer. But it is also singular in its proposal that the highly aestheticized shape and size of such appliances could provoke (sometimes violently) affective responses from their owners, a relationship between object and individual usually reserved for discussions about sculpture, installations and abstract art.

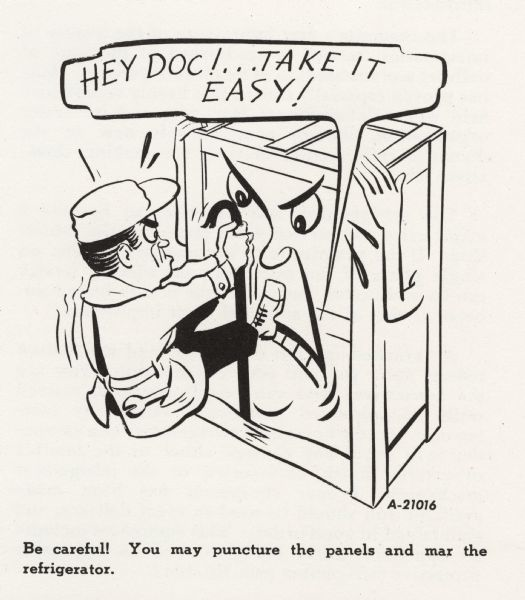

Woody Harrelson’s character, Kelly, is an archetype of fallen paterfamilias: jobless, drunken and enraged, a spin on Ralph Kramden (Jackie Gleason) of The Honeymooners (1955-1956). Following that early TV show’s preference for placing Ralph in confrontation with each element of progressive American design and technology that his wife Alice desires, Kelly’s makeshift den in the family kitchen is challenged by the sudden appearance of the freezer that his wife Evelyn wins.4 This contentious spatial dynamic has some historical precedent: Laura Shapiro comments that the home freezer, foisted upon postwar consumers by advertisers and manufacturers to help boost the frozen food market, had a prolonged and awkward period of introduction into suburbia. Freezers were dumped in bedrooms, hallways and living rooms in a vain attempt to find a proper place for the appliance. A variety of designs were employed to hide or reduce its cumbersome bulk, including a coverlet that transformed the freezer into an ersatz radio, or an additional foldout sheet of metal that turned it into an ironing board.5 Kelly’s freezer has none of these gimmicks so its presence is therefore inescapable. It offers only a single function: to chill the steaks and ice cream that Kelly cannot afford to buy his family, clearly revealing his inadequacy within a 1950s America purportedly brimming with capable breadwinners.

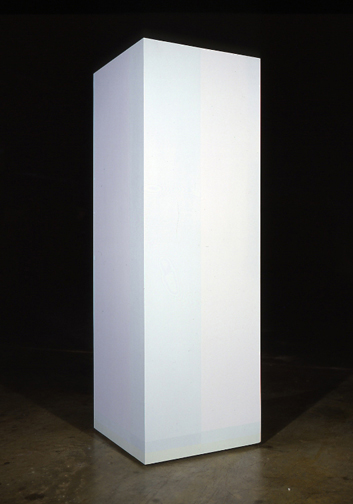

In addition to its lack of ameliorative adornment, the Deep Freeze is also simply in the way. Far from upholding midcentury industrial design’s promise that products would melt seamlessly into daily life as unobtrusive servants, this freezer is arranged within the kitchen to resemble the obelisk of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): huge and impenetrable, its exact purpose and power undefined. This is no ordinary cold storage. It is imbued with a lurking presence by the filmmakers, inexplicably brightly lit and hovering prominently in the background throughout the entire film. And like Kubrick’s set designed monument, this freezer’s inscrutability eventually causes a ferocious outburst – coming in this case from Kelly. Midway through the film, he drunkenly stumbles against the freezer. In a flash he finds an iron skillet and bludgeons the offending appliance. The freezer ostensibly receives a beating because it symbolizes Kelly’s financial and familial shortcomings, as well as his wife’s ability to provide their home with cutting edge technology. Yet his reaction is also due in part to the appliance’s “gross clatter” of available space, or, as Kelly puts it, “This goddamn thing is too big for this goddamn house!!”6

Since The Prize Winner chooses to treat the freezer as much more than a box to store Birdseye fish sticks, Kelly’s explosive reaction is an illuminating reminder that midcentury appliances are not merely utilitarian. They are enshrouded in design. And such design provokes complex sensory responses from those who interact with these objects, a point long debated between art critics, museum curators, and industrial designers, many of whom identified as artists. In this case, it is not incredible to believe that modernist freezers, fridges and other large appliances might share the characteristics of “Specific Objects” or “ABC Art.” First appearing in the early 1960s, these three-dimensional works evolved from, invoked and commented upon modernist industrial design, sharing a focus on pure, basic forms, mass-produced materials, and evidence of mechanical rather than human construction. And as Michael Fried points out, they radiate a peculiarly “disquieting” effect.7 Their physicality is suggestive of a malignant apparition awaiting interaction with a person. Fried notes, “…once [an individual] is in the room the work refuses, obstinately, to let him alone – which is to say, it refuses to stop confronting him, distancing him, isolating him.”8 The Prize Winner approximates this experience in the kitchen, indicating that an appliance out of place, or without a historically defined place in the household, can be a formidable thing to encounter – as bizarre and unsettling as unexpectedly encountering an Anne Truitt rectangle in a gallery.

Responding to any of these forms with an iron skillet is not going to diminish their effect. The dislocating power of the Deep Freeze is finally and entirely due to an aggressive blankness distilled into perpetuity within its high-art siblings. It reveals nothing of its human origins, cloaked in a fashion incomprehensible to Kelly. He shares none of the determination of working and lower-middle class housewives who personalized otherwise bleakly mass-produced commodities in the 1950s. These women banded together through product research groups to successfully pressure refrigerator corporations into producing decidedly anti-modernist, chrome-encrusted “Cadillac” appliances that visually expressed their complex socioeconomic identities and tastes.9 Kelly’s freezer, by contrast, remains inhuman and intrusive: designed, created and placed within the household by forces totally beyond his ken. As The Prize Winner therefore recreates fleeting first impressions of a new product that has since been subsumed into banality and invisibility, its use of a freezer is far from perfunctory or kitsch. The film finds a dimensionality and style that is surprisingly deeply unresolved, uniquely confrontational to each member of the suburban family. And it also presents a paradox for viewers like myself, providing a retrospective, imagined physicality that complicates any desires to return to the age of Tomorrowland, and live side by side with the high tide of industrial design.

Image Credits:

1. Chilled Futurism

2. The Big Clock (1948)

3. Woody Harrelson, Julianne Moore, and the freezer in The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio (2005)

4. Bludgeoning the Icebox

5. Minimalist fridge? Anne Truitt, Landfall, 1970

, acrylic on wood,

73 3/8″ x 23 7/8 x 24″

Please feel free to comment.

- Terry Smith, “‘Pure Modernism, Inc.,” Making the Modern: Industry, Art, and Design in America, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 385-405. [↩]

- Smith, “Designing Design: Modernity for Sale,” 379. [↩]

- Shelley Nickles, “More Is Better: Mass Consumption, Gender, and Class Identity in Postwar America,” American Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 4, (December 2002), 596, 599-601, 609. [↩]

- For an in-depth analysis of working-class families and their relationship to postwar commodities as seen on early television programs, see George Lipsitz, “The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class, and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs,” Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 1, No. 4 (November, 1986), 362-367. [↩]

- Laura Shapiro, “Introduction,” Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America, (New York: Viking, 2004), 16-17. [↩]

- Smith, “Designing Design: Modernity for Sale,” 353. [↩]

- Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 155-156. [↩]

- Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” 163-164. [↩]

- Nickles, “More Is Better,” 588-590. [↩]

Hi Paul,

This is a really great article about a topic that I don’t think I have ever previously considered while watching films or TV. And the cartoon you found is perfect.

So do you think that this kind of reaction also applies to other appliances, like the washing machine?

Paul:

Very articulate observations regarding socioeconomic trends reflected in the film industry. Your remarks invite us to consider the pressures placed on society to attain and keep pace with current fads – well done!

Amelia

Pingback: Back to School Links! | Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style

Great article thanks for sharing this great article

Great y