While you were out: The Canadian Media Have Disappeared

Dr. Zoë Druick / Simon Fraser University

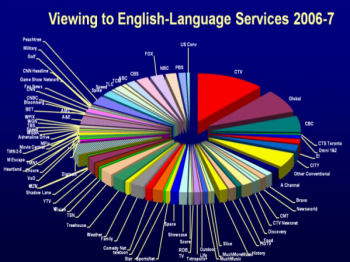

Late last month, the CRTC, Canada’s broadcast regulator, released a decision to allow private television networks in Canada to sell content to cable and satellite carriers. This decision was made, according to the regulator, to acknowledge the fact that television industry in Canada has emerged as a set of digital bundles owned by three dominant groups: CTV Globemedia Inc., Canwest Television Ltd Partnerships, and Rogers Communication.1

Private broadcasters are losing money, apparently, partly because they are spending record amounts on foreign (read American) content. Nevertheless, all three companies are diversified into different media and on-line ventures, including wireless. Losses today are part of a shifting business plan and with these kinds of decisions from the CRTC, private broadcasters will be in no doubt that the regulator is on their side. Predictably enough, this decision has riled the cable companies, ventures that provide no content and made something in the vicinity of 25% profits last year, although public response seems muted. The issue of negotiating fees is being brought to the Federal Court of Appeal.

None of this may sound too earth-shaking. The privatization of the Canadian media and the relaxing of ownership rules has been underway ever since the air first buzzed with broadcast signals in the 1920s. But a number of key shifts are implied by this decision nonetheless.

For starters, this decision may be the way the CRTC is backing into a series of difficult policy issues related to digital platforms and new media usage patterns. Canada isn’t set for the digital TV switch over until August 2011, but many people are already making their own digital sets from their computers. In the same week as the decision was released, Ipsos Reid announced the results of a poll of Canadian leisure time that claimed that internet usage has just edged out television watching: 18 hours to 17. 2 That’s per person per week. Needless to say, some of those internet hours are spent watching TV shows. On the internet there are no Canadian content laws. In fact, Jacob Glick, a representative of Google, said recently that such restrictive content laws are not even necessary anymore. “More Canadian content can be seen, created and enjoyed in ways never before possible,” Glick announced to a House of Commons committee convened to study the effects of new media on Canadian culture. 3 If fees are passed on to subscribers by the cable companies, as they’ve suggested they’ll do, viewers may decide to cancel cable altogether and tune in through the internet. This is a country where changes in cable packages and pricing can bring citizens out into the streets. This is what happened in 1995 when Rogers added a new fee of $2.65 to cable bills for an additional seven Canadian specialty channels. Subscribers didn’t have to keep the channels, but they needed to specify that they didn’t want them in order to avoid the hike (the so-called negative billing option). Canadians showed their wrath (was it the $30 per year, or the ready access to hours and hours of Canadian-produced content? Maybe both) and the strategy was duly changed.4

Knowing that Canadians are very touchy about their cable bill, the decision to force the cable companies to negotiate fees with the broadcasters—and most likely raise their fees to keep up their robust profits—does seem like a crucial aspect of this decision. But perhaps it is a smokescreen for an even more insidious question and one that the Canadian government has been cautiously avoiding: copyright.

It turns out that the negotiation of fees hinges on the issue of copyright as rebroadcasting is a form of copying or dissemination. The current act regulating copyright is 25 years old. It doesn’t even begin to cover issues central to the digital age. In the absence of legislation, the most recent case being used to govern issues of copyright was heard by the Supreme Court in 2004 (CCH Canadian ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada). It concerns photocopying. There is no doubt that the Copyright Act requires updating. Yet the way in which the legislation is crafted will be crucial for the Canadian public. Will fair dealing be given the same weight as the rights of large copyright holders? Will educational exemptions be made sacrosanct? This question is germane in relation to this CRTC decision. Will forcing the courts to define copyright in relation to program relay have some effect on internet television practices, including streaming and re-mixing? Does making a decision with regard to copyright as it pertains to corporate revenue risk leaving the public out of the equation?

As part of this decision, the CRTC also demanded that networks continue to spend at least 30% of their revenue on making Canadian TV shows, about where the level of spending has been for the past few years. In addition, 5% of gross revenue must be spent on programs of “national interest” (documentaries and children’s programs mostly), 75% of which must be allocated to programming created by independent producers. However, with revenues at all-time lows, this doesn’t translate into strong support for beleaguered Canadian producers. However, a few days later, the government announced a new $350 million Canadian Media Fund, which sounded pretty good.5 Turns out this isn’t actually new money, though. It combines, and slightly enlarges, the current Canadian Television and Canadian New Media Funds. This makes some sense: the funds are converging in the same way the media are. The flip side of this new political economy of production, however, is that producers are compelled to produce content for multiple platforms. A documentary film must have on-line content to go along with it. A journalist must also have a blog. All of this convergence means that there may actually be less content drawn out across more formats. These light regulations on the industry mean very little for media producers. Cultural producers are being forced into the “free” provision of their work on the internet, clearly not a strategy that bodes well for the fostering of new talent.

Hubert T. Lacroix, president and CEO of the CBC, called this decision a “dark day” for the public broadcaster.6 Left out of the decision altogether because it is constitutionally prevented from selling its signal as part of its mandate of public service, the CBC is being rendered less and less relevant in the Canadian media landscape with each passing day. As any university professor in Canada can attest, our students are only dimly aware of the CBC and are not piqued by that fondly felt frustration that is familiar to many of us who grew up in the 20th century. Its programming decisions on television and radio to play the entertainment game have meant the alienation of many older viewers as well.

Clearly, Canadian culture, like local news, is a relic of a bygone era. Both are replaced by statistics of minutes spent in front of screens and the new imperatives of digital leisure. With the decision to open up the market to foreign-owned wireless providers Global Live and Wind Mobile made by the federal government last month, it seems only a matter of time before the same fate befalls any of the digital leisure providers.7 From there, the national television and film industry will be nothing but a memory. Even Youtube Canada, launched in 2007, has become a rivulet in the ocean that is Youtube. The unfortunate aspect of all this is that it proves what the critics have said all along about communicative capitalism. 8 It only simulates the democratic potentials that it simultaneously eradicates. The worst part is, it happens right before our eyes through a series of mind-numbing policy decisions like this one. And before you know it, the hope of Canadian broadcasting—and the internet for that matter—is sadly dashed.

Image Credits:

1.CRTC: Canada’s Broadcast Regulator

2.Viewing to English Language Services

3.The government announced a new $350 million Canadian Media Fund

Please feel free to comment.

- Susan Krashinsky, “CRTC” favours broadcasters in TV shakeup ” The Globe and Mail. March 23, 2010. A1. [↩]

- “Weekly Internet Usage Overtakes Television Watching.” Ipsos website, March 22, 2010 (http://www.ipsos-na.com/newspolls/pressrelease.aspx?id=4720). Accessed April 1, 2010. [↩]

- Bill Curry, “No room for Canadian content rules online, Google warns MPs.” The Globe and Mail. March 3, 2010, A6. [↩]

- D’Arcy Jenish, “Cable gets zapped: a wave of consumer protest prompts Rogers to rethink the launch of new channels,” Maclean’s 1995

(http://www.faqs.org/abstracts/News-opinion-and-commentary/Cable-gets-zapped-a-wave-of-consumer-protest-prompts-rogers-to-rethink-the-launch-of-new-channels.html) Accessed April 1, 2010 [↩] - “The Canada New Media Fund will launch April 1, 2010.” Telefilm website. http://www.telefilm.gc.ca/03/311.asp?lang=en&fond_id=3) Accessed April 1, 2010. [↩]

- “Dark day for public broadcasting: CBC/Radio-Canada denied value-for-signal by CRTC.” Press release. CBC website. March 22, 2010. (http://www.cbc.radio-canada.ca/valueforsignal/home.shtml). Accessed April 1, 2010. [↩]

- Jacquie McNish, “CRTC decision won’t end network-cable slugfest.” The Globe and Mail. March 23, 2010, A2. [↩]

- Jodi Dean, Publicity’s Secret: How Technoculture Capitalizes on Democracy. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2002. [↩]

Concerts on Demand

On Sunday, November 16th, 2009, the CBC Radio Orchestra gave it’s last concert. The CBC Orchestras flourished since 1938 in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax. These orchestras were patrons of Canadian performing artists and composers, including women composers such as Violet Archer who studied with Bela Bartok and Paul Hindemith and went on to become Chair of Music at the University of Alberta while continuing to write music.

In September of 2009 the National Broadcast Orchestra of Vancouver was launched to make up for the loss of the CBC Orchestras around the country. Spearheaded by Montreal businessman, Philippe Labelle, the orchestra has as it’s primary outlet, the internet. The NBO has it’s own website: http://nboc.ca. Looking at the website, one senses an air of cheerfulness. This new orchestra aims to be more liberal and all encompassing than it’s predecessor. Now a registered charity, the orchestra survives by donations and concerts.

Dr. Druick writes of the necessity of audiences with ‘digital leisure’ time. Let’s hope that more and more listeners will tune into the NBO or schedule it on their iPods so that they listen to concerts while jogging or when caught in traffic on the way home from work. Of course tickets to live concerts are also availble. But what about Canadians on the other side of the country who have no easy access to Vancouver?

Our view of Canada as a country where the people are friendly and apologetic, that offers free medicine and supports the arts may have to change as Canada becomes more and more like everyplace else. Soon Canadias really will have something to apologize for.