Watching for Botox

Julia Lesage / University of Oregon

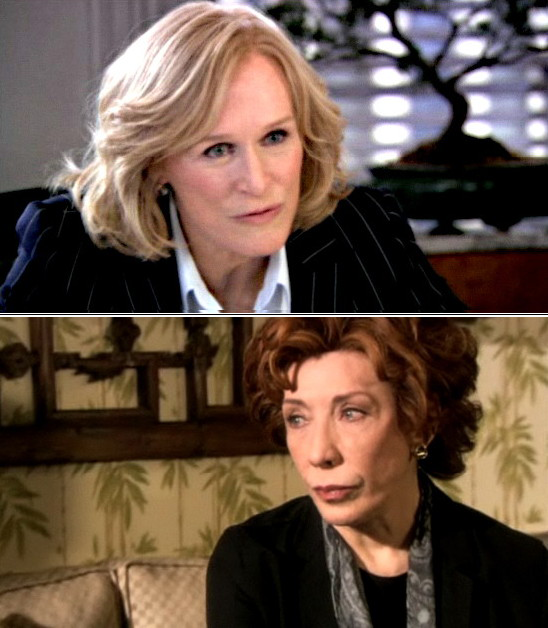

On my TIVO this season is the legal drama Damages, which I enjoy for its innovative narrative structure, tough-minded female protagonist, and all of the major actors’ seeming use of botox.1 In particular, Glenn Close, the protagonist, and Lily Tomlin, who plays a Bernie-Madoff-type swindler’s wife, have the smooth waxy skin and relatively immobile facial muscles that indicate this neurotoxin has cosmetically eliminated their wrinkles. I’m not alone in looking for botox. Many middle class women viewers of my cohort, age 70+, read faces this way, both on TV and in daily life.

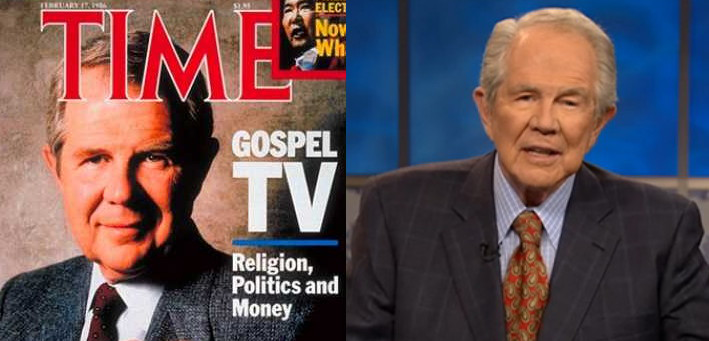

This short autoethnographic TV-viewing observation draws on both my televisual habitus and idiolect. By habitus, I refer to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept that the communities or “class fractions” one belongs to shape a person’s way of thinking, behavior, and “classifying practices” or taste.2 These are the communities that shape my “distinction”: middle class, female, white, senior retiree, intelligentsia: within the latter, Marxist, media scholar, second wave U.S. feminist. In addition, I have a TV-watching idiolect, a specific way of watching unique to me as an individual, particularly shaped by my life circumstances and personal history.3 One element shaping my watching for botox is the fact that I have written on Pat Robertson and The 700 Club, and as I have watched this program over the years, I’ve thought he must have the world’s best plastic surgeons because he hardly ever seems to age.

In addition, I have a personal history with avoiding botox. In the 1990s I lost my voice completely, which could have put an early end to my teaching career. Insurance would only pay for botox injections into the vocal chords, which a user told me often led her to have to no voice at all for the first two weeks after her injection; in addition, she had to repeat such a process about every four months. Rejecting the injections, I opted for expensive voice therapy in LA with a voice coach “to the stars.” In recent years I have come to terms with the fact that many medicines are derived from poisons, but this is one I made a firm decision about.

Right now, perhaps because botox is so visible on Damages, I want to reflect on how cosmetic surgery appears on television and in public life, and why. Many people may have noticed how Hillary Clinton’s appearance changed when she was running for President and how she now looks as Secretary of State. Perhaps fewer have thought about Bill’s comparable changes, but side by side pictures indicate that both use botox and have had plastic surgery. It’s well done work, since wrinkles remain around the eyes and confirm facial expressivity is intact. My judgment—good job or cosmetic surgery gone wrong—accompanies my evaluative face viewing, either in TV watching or personal interactions. If it’s a really good job, I shouldn’t be noticing at all.

Currently, for many people in the upper-middle class in the United States and perhaps in other parts of the world, face lifts and the cheaper alternative, botox, have become the norm, a regular medicalized procedure they undergo to increase job potential, gain status or erotic opportunity, and achieve control over their social mobility and class position in a constantly unstable world. If Lily Tomlin no longer has the wonderfully expressive face she had as a comedienne, in Damages her appearance well matches her role as a tastefully coiffed and botoxed rich-man’s-wife. In this show, most of the characters are upper-middle class, so that the actors’ cosmetically worked-on faces fit well with the narrative’s entrepreneurial psychology, one that neoliberalism now imposes on the managerial class: work on yourself, develop yourself, make good choices, take charge of your life—especially in terms of services you can buy.

In current television and popular culture, there is a significant division between connotative imagery, as in the photos above of actors and public figures, and the televisual narrativization of plastic surgery and other personal “makeovers.” On the one hand, we have that which is merely suggested. On the other, we have shows such as Extreme Makeover, The Biggest Loser, or What Not to Wear which depict how people, often lower middle class or working class, submit to regimens of authority dictated by experts in the fields of fashion, personal appearance, and physical culture. These are disciplinary regimes, as described by Michel Foucault; the shows’ participants are expected to internalize the experts’ norms. Both within the shows and in the eyes of viewers, all the minute aspects of the participants’ bodies are judged, evaluated, objectified, and constantly measured for deviation and conformity. Those on the makeover shows are rehabilitated through monitoring and regulation—both the authorities’ taste and their own internalization of the authorities’ norms.

Looking at both these kinds of representations, one narrativized and one merely connotative, I revisit my own impulse to watch for the botox. The makeover shows are the most overtly narrativized and the least interesting to me, partly because their disciplinary aspect and/or overt consumerism in regards to plastic surgery repels me. But these shows also play a major role in popularizing “working on one’s body,” with a shopping list of what can be bought, including details about what to ask for. Thus the makeover shows contribute to a consumer culture in which botox literally becomes “normalized.” The other group of representations, so much harder to pin down in terms of who has gotten what procedure, tell me about how many people in the “public eye” are now required to get injected with botox or go under the knife. And they have to pay a lot because less change is more effective in this kind of self-improvement, so that procedures might have to be undergone more often, using the best, most expensive cosmetic surgeons. In what is elided and what is enunciated on television, the real-life rich and powerful have more privacy just as they are more likely to get “good work” on their faces. For our purpose as media scholars, as Lynne Joyrich has pointed out in her foundational essay, “Epistemology of the Console,” we need to consider both kinds of televisual presence simultaneously to evaluate how the media deal with modifying personal appearance at this specific moment in our cultural history. One group’s body modification remains an open secret but still largely in the closet, while the other’s is excessively narrativized in a judgmental way.4

Image Credits:

1. Glenn Close, age 63. Lily Tomlin, age 71

2. Pat Robertson: Age 53 and age 80

3. Hillary Clinton, age 61. Bill Clinton, age 62

Please feel free to comment.

- Amanda Fortini, “Lines, please—If you can’t move your face, can you still act with it?” New York Magazine, Mar 7, 2010: http://nymag.com/movies/features/64504/ [↩]

- In French, both classifying practices and taste are referred to by the word “distinction.” Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice. Paris: Minuit, 1987; London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984. [↩]

- The term “idiolect” comes from linguistics and refers to a person’s unique pattern of language use. [↩]

- Lynne Joyrich, “Epistemology of the Console,” Critical Inquiry 27 (2001): 439–67. [↩]

A very interesting article, Julia! I quite liked your conclusion regarding the two discourses of body modification, but I wonder if there is also a flipside to “watching for botox.” If we constantly speculate on, look for, or attribute aging beauty to medical and technological interventions such as botox, are we not delegitimizing the idea of someone “aging gracefully” or even–at the extreme–natural beauty after a certain age?

Thanks for such a thoughtful piece!!!!! The botox effect might also be thought about in relation to the more general pharmaceutical takeover of US television.

Charlotte, the motive behind my botox-watching is alarm, especially when I think about the extent to which public figures are more and more compelled to surgically enhance their appearance, which in my eyes often is not enhancement. Furthermore, televisually, such an visual presence of powerful, rich, and good-looking elders who do use cosmetic injections and surgery could lead many viewers to judge me and my peers, those whom Mary Daly praises as crones, as deficient in our personal upkeep. I see this partly in terms of what Foucault analyzes as disciplinarity, but more often it seems just self-protective, common-sense thinking for a senior. I know that the elderly experience a great pressure to keep up appearances, since unkemptness or, worse, dirtiness is one of the reasons that we finally get locked up. Those who want to be in the center of power and not relegated ever further to the margins have to look as much as they can like those who are already powerful. It’s an old theme in literature, learning to dress properly to fit into the middle class, but TV, and especially HDTV, have taken the issue of “being presentable” to a whole new level. It’s when viewers just don’t notice the botox that we should really be alarmed.

This is a very interesting article, it certainly made me think about my own attitudes to plastic surgery. I have always been repelled by the idea of going under the knife for what I always saw as shallow, verging on material gain…This has been fuelled by programs such as “I want a famous face”, that disgusting old MTV show where people would get plastic surgery to look like famous pop stars….I have never explored the other side, maybe none of us have really been able to REALLY explore the other side, those like you say in society who motives are more logical when considering surgery, those out of the spotlight ie the elitist, who bow to I imagine the whip of capitalism.