Dracu-fictions and Brand Romania

Anikó Imre and Alice Bardan / University of Southern California

To claim that we live in a global brand culture probably doesn’t require much argument. Branding has gone far beyond linking a product with a name and logo; it has become an organizing principle of communication, identities, even political activism. However, it might still be odd to think of entire countries as branded. In fact, while the notion of country or nation-branding might be relatively new, it is not so counter-intuitive. Borrowing the language of branding specialists, globalization pits nation-states against each other today in an economic competition that hinges on products, tourism, and foreign direct investment. Nation-branding as a field of research emerged in the 1990s at the intersection of marketing and public diplomacy; and focuses on how state governments, hand in hand with corporations and marketing agencies, manage their country’s image in the global marketplace. While marketing research normalizes such practices as not only inevitable but also desirable and progressive, nation-branding also brings up a number of critical issues.

First of all, such a paradoxical, “postnational” remapping of the world as a series of competing nation-brands tends to reinforce neo-imperial inequalities among nation-states. States that have established powerful brands thanks to their long-standing economic power, tradition, cultural and touristic offerings or products are at a significant advantage compared with smaller countries with weak or damaged brands, or with countries with non-existing brands, such as the new successor states of Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union. Here we examine one of these disadvantaged cases, that of “brand Romania.” We focus on a significant obstacle to Romania’s reinvention as a competitive brand: American and Western European films’ and television programs’ recent, renewed investment in the interlinked legacies of Count Dracula, the terror of Transylvania, and of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, a modern-day vampire, whose oppressive reign ended in his bloody execution in December 1989. As we show through four snapshots, a recent series of (pseudo-)documentary representations have rekindled this double legacy and fixed Romania as a repository of images that evoke, link and deploy for commercial purposes Cold War and medieval backwardness.

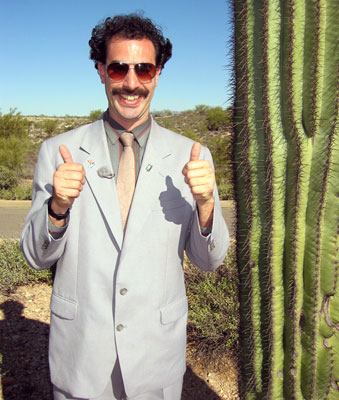

#1 — Borat

As is well-known, the “Kazakh” scenes of Sasha Baron Cohen’s mockumentary were filmed in the Romanian Gypsy village of Glod. Kazakhstan, a post-Soviet republic with vast oil resources, engaged in a diplomacy battle with Cohen for tarnishing its image. However, it turned out that the country had been too unknown for most viewers to be tarnished. Since the film generated curiosity and boosted the tourist industry, the Kazakh state eventually ended up playing along and reluctantly incorporated the Borat character as a publicity figure in the service of its own state-branding strategy. At the same time, the images of a cow in the living room, toothless men, muddy streets, incestuous families and rampant anti-Semitism, confirmed Cold War stereotypes of a primitive Eastern Europe and attached these to Romania for comic purposes. The noise of post-Borat protest by misled and undercompensated local Romanian extras was drowned out by the film’s own publicity campaign and critical reception, which revolved around the US as the film’s real target of mockery. The producers’ blithe use of rural Romania also effaced the fact that the locals in the film were Gypsies, who themselves suffer violent discrimination from the government and much of the Romanian population. Borat subsequently became a reference point for a number of television reality shows, which looked for and found in Romania the same cluster of poverty, medieval mysticism, and the irreparable, imposing shadow of communist dictatorship.

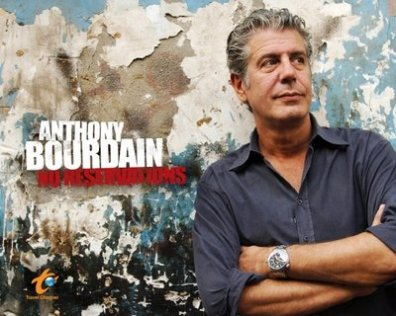

#2 — No Reservations

The Romanian episode of the Travel Channel’s popular travel-food series No Reservations, which aired on February 25, 2008, became notorious among viewers as the “worst episode ever.” While the host, Anthony Bourdain, is known for his disregard for political correctness, this particular episode is punctuated throughout by his satirical grumbles in both voice-over and on-screen dialogues. The show opens with his companion-sidekick, Russian Zamir biting into a never-ending sausage, greetings locals as “comrades.” Over the images of dark and foreboding mountains, Bourdain’s voice-over introduces Romania “and its mythical region of Transylvania” as a “grey and distant place,” which lies “deep in the heart of Eastern Europe.” Standing in a Bucharest street, he adds, “There were some creepy communists here. I like that too, you know.” His tasting tour includes two stops: One is Bucharest, where he and Zamir shake their heads at Ceausescu’s megalomaniac constructions and listen, bemused, to a local witness’s account of the revolutionary events that led to the dictator’s demise. The other one is rural Transylvania, where they shake their heads at local efforts to turn Dracula into a tourist theme and mock the Dacia, “Romania’s national car,” “a strangely unbalanced structure on tiny wheels.”

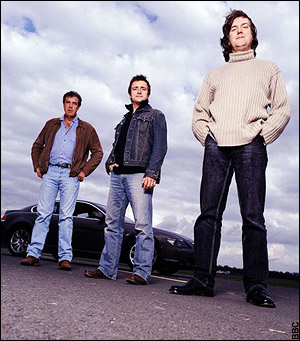

#3 — Top Gear

BBC 2’s most watched show, broadcast in over 100 countries, traveled to Romania in November of 2009 to try out the hosts’ choice of cars for the episode. Jeremy Clark and his two regular companions drove an Aston Martin DBS Volante, a Ferrari California and a Lamborghini Gallardo Spyder down the Transfagarasan Highway, a road built by Nicolae Ceausescu. Their adventures in “Borat country,” as they called Romania, included a stop in Bucharest’s Revolutionary Square to marvel at Ceausescu’s enormous former residence, the House of the People, and in a Gypsy village, where they were successfully stormed by curious Roma children, made fun of the Dacia, and got stuck on a narrow bridge in an unpaved, one-lane road. “Coming here in a car that cost £168,000, is a bit like turning up in the Sudan in a suit made entirely out of food,” as Clarkson commented light-heartedly, and without a hint of self-criticism.

#4 — Whopper Virgins and Folgers Commercials

Perhaps the most widely circulating and thus most damaging instance of the “primitive Romania” brand are two commercials that first aired on December 8, 2008. In the first one, a wintry Victorian tableau of a poor village dwelling hidden among dark mountains, identified as “Romania,” comes to life when an American Aid worker receives a package containing a precious jar of Folgers coffee. The locals gather around him, staring in amazement as he prepares his coffee in a makeshift cheesecloth coffee filter, anticipating their lives to be brightened by Folgers. In the other ad, “Romanian” villagers, dressed in folk costumes, taste-test Burger King whoppers “for the first time.” As the mayor of Budesti, where the ad was filmed, explains, although he had refused to get involved in giving the producers permission for their “experiment,” they ignored him and proceeded to do a “casting” call for a “documentary” at a local restaurant, where they paid willing participants about $40 “just for tasting some food.” The portrayal of Romania as a forgotten land full of “Whopper virgins” is so blatant in these ads that it even inspired a Saturday Night Live spoof on January 10, 2009. However, SNL’s “the making of the ad” skit, based on the Whopper Virgins campaign’s own online docu-mercial teasers, turned out to be yet another parody of local Romanians so backward that they are unable to hold a cheeseburger properly, or try to run off with it “to feed their whole village.”

These examples identify Romania, more than any other postsocialist country, as a site of dark television and movie tourism, the last vestige of grit and shock on which Western media producers and audiences can draw to reinvent the horrors of the Cold War as commercial docu-kitsch, which, at the same time, is the authentic condition of a strange, primitive people descended from a vampire count. The arrogance of such representations is in disavowing their own roles in forcing locals to perform the pitiful primitive to attract international attention and revenue. As in the aftermath of Borat, Romanians’ outraged, and, in some cases, traumatized reactions to such representations rarely left Romania. The feelings of betrayal that the shows and ads caused or the state’s letters of complaint to the respective production companies hardly made international news. Clearly, despite the optimism around nation-branding as a practice and field of research, the neoliberal marketplace does not automatically open up opportunities for all states and peoples to rebrand themselves in a positive light and ignores the branding power embedded in seemingly trivial media representations.

Image Credits:

1. The Romanian Flag

2. Happy Times Borat

3. Anthony Bourdain

4. The Top Gear Crew

Please feel free to comment.

This was a very interesting article. As an outsider to this region, I didn’t realize how branded the Dracula myth really is throughout television and popular media. With the increase of visual culture, this original literary creation has expanded exponentially into other formats, though as we see in the article, through repeated stereotypes. Thanks for including those video clips as well.

What a thoughtful and useful piece. Dina Iordanova gives an interesting account of Romanian efforts to re-appropriate Dracula in her essay “Cashing in on Dracula: Eastern Europe’s Hard Sells” (Framework, 2007). She places emphasis on the complexities of self-exoticization, writing, “It is not just ‘the West’ which constructs the Balkans compliant to Western stereotypes; this construction is taken up and carried further to a large extent by locally-based cultural entrepreneurs themselves, and the resulting voluntary self-exoticism becomes a common mode of self-representation.”

One high-profile platform for intense nation-branding can be found in the ad slots on CNN International which are full of commercials for countries like Armenia, Montenegro and Egypt that variously solicit business investment and tourism. The verbal rhetoric and visual imagery of these ads is fascinating. My sense is that some representational change is appearing in this category as the recession has killed off previously energetic attempts to develop countries like Romania and Bulgaria for tourism in general and for the holiday home market in particular.

Thanks for the comments, Anna and Diane. Dina Iordanova’s essay is very much aligned with our argument. Thanks for the CNN International suggestion. We’ll check it out for the longer and more theoretical version of this paper, which is forthcoming in Nadia Kaneva’s edited book on nation-branding and postsocialism.

I’m relieved to see that at least one person is tackling this topic in the academic realm … let’s hope the defense of Romania’s national image (or at least the right of countries like Romania to have a say in thier own re-branding) is taken up in the secular sector (ie mainstream entertainment media) as well! I have a much less scholarly, though I hope sympathetic, blog on the history and pop culture of Romania. Judging from the responses I’ve had from non-Romanian friends, there’s a lot of work to be done on balancing out Imre’s snapshots with something a little more in-depth and sensitive to the complex character of this country.

Multumesc, Aniko!

read and review “DRACULA IS DEAD”by former ambassador to romania.I ve lived 6 years in the USA,I came to realise and understand the meaning of the old saying “ignorance gives birth to everyday monsters”.that s why i choose to return to civilised world,in europe.

You mentioned SNL’s spoof of the whopper commercial. I’d be interested in your thoughts on SNL’s depiction of Romanian “otherness” with respect to Gilda Radner’s impression of gymnast, Nadia Comaneci (which, like other Dracu-fictionalizations, seemed to have come and gone on the web’s sphere of locate-ability).

Further, is dracu-fiction a new obsession with Romanian culture or is it the last vestiges of a bygone Soviet-focused era? Do we create nostalgia in our backwards, Soviet-esque turn to Dracu-fiction because our current “enemy” lacks Hollywood’s Cold War glamour?

You have really nice content. Thank you for sharing.