In Search of Bigfoot:

The Use and Obsolescence of Bionics

I vaguely recall a trip to a county fair in Connecticut with my grandparents in the mid-1970s; what caught my attention was a display in the science exhibit. One in a series of shadow boxes hung underneath a tent at the furthest reaches of the fairground contained a prototype for a bionic arm, and was contextualized by a didactic panel that suggested the arm would likely be a part of everyday life in the not too distant future. As this is indeed such a vague memory, I can’t testify as to the authenticity of the artifact, but I do recall some mention that the arm had already been field tested on an amputee. Regardless of the truthfulness of the claim or the arm itself, science was clearly capitalizing on the popularity of broadcasting’s dual odes to bionics; and I was hooked. Like many boys in my peer group, I didn’t simply watch The Six Million Dollar Man; I indulged in the fantasy of being bionic. Though I was equally enamored with The Bionic Woman, I did not make that fixation public.

NBC’s resurrection of (The) Bionic Woman has prompted me to think through the contemporary relevance of bionics, and map its reintroduction against the popular imaginary of the mid-1970s. The seventies is a decade marked by a resurgence of science fiction and fantasy programming, developed by ABC but replicated across all three major networks, exemplified by programs such as The Bionic Woman, The Incredible Hulk, The Invisible Man, The Man from Atlantis, The Six Million Dollar Man, The Amazing Spiderman, and The New, Original Wonder Woman. The television landscape of the 1970s reflects a general turn in programming away from the documentary boom of the 1960s. Yet there is a specific turn toward relevance manifest even across those fictional series developed during the decade. A number of televisual and extra-televisual factors inform this shift, including the refinement of demographic measures (with the development of A.C. Nielsen’s people meters), the changing face of the industry (with the rise of independent production companies), and the specific dynamics of the social and political climate. For advertisers, these trends were captured by new demographic categories, which also took into consideration a recessionary cycle that forced more women to seek employment outside the home. In the mid-1970s, socio-economic shifts pressured advertisers and networks to further narrow their notion of the audience and to modify programming practices during prime time. CBS capitalized on the many anxieties of the period by turning to urban realism (with such sitcoms as All in the Family and M*A*S*H), developing interests across the generation gap, while ABC engaged in counter-programming for the youth market by resurrecting the science fiction and fantasy genres, a cyclical return to proven terrain. Yet this industrial history does not account for the success of such industry trends, nor does it answer the more ideologically inflected questions about television’s relevance as a cultural forum.

Title Sequence from the original Bionic Woman

The cultural climate of the 1970s was one that reflected a growing disillusionment with government (and the television industry was a window to the world, made quite apparent by Nixon’s televised resignation in August 1974), while significant technological advances reshaped domestic entertainment and revitalized scientific exploration, yet also threatened national security and redefined the very sense of self. Against this socio-cultural backdrop, the programming trends in the 1970s recount the fantastic elements of the quotidian and the surreal horrors of everyday life. Watergate, Love Canal and Three Mile Island were undeniable signs of institutional failure and neglect within national borders, while the Vietnam War and the siege at the Munich Olympics were just two of several events on the international stage that signified more significant failures in foreign policy.

It is not surprising that science fiction and fantasy found a renewed place on television in the 1970s, as these particular genres are often the site at which cultural and technological anxieties seem to intersect. These anxieties seem to be a principle part of the formative dynamic and subsequent function of the superhuman as a stalwart signifier across network television throughout the decade; primetime television featured superheroes employed by a wide array of clandestine research corporations and government intelligence agencies (Diana Prince (Lynda Carter) at the IADC, Steve Austin (Lee Majors) and Jaime Sommers (Lindsay Wagner) at the OSI), all invested in protecting truth, justice, and the American way either through active defense or informed scientific inquiry.

Alongside these fantastic indulgences, on a weekly basis during the second half of the decade, Leonard Nimoy helped explain away a broad range of mysterious phenomena on In Search of…. Merging fantasy with reality, the investigative program adopted a loose journalistic approach as it tackled both historic events (e.g. the sinking of the Titanic and Lincoln’s assassination) and real persons (such as Amelia Earhart, Jimmy Hoffa, and Jack the Ripper) that had become subjects of folklore, and scrutinized timeless paranormal and pseudoscientific matters (such as ghosts, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster). The Watergate probe had its legacy written across the face of television; inquiry had no bounds.

It is on the matter of inquiry that I turn my attention to more recent incarnations of bionics. My goal is to consider the tenuous nature of fantasy. My investment in the childhood episode that introduces this essay is part of an ongoing struggle about the assignment of meaning, perhaps symptomatic of a perpetual engagement with the old academic hat trick of reading media “through” a decade. Jane Feuer’s Seeing Through the Eighties (Duke University Press, 1995) is a prime example of an effort to solidify meaning; yet the most satisfying part of her enterprise is the foundation that is sketched out, the traces of the landscape, industrial or otherwise. The difficulty I have with such projects is in the close analysis; and this not a critique of her project but rather a consideration of a problem endemic to such analyses, including my own. I am suspect of any enterprise that tries to succinctly connect the dots, to neatly map form and content onto context. But these exercises form an important part of any developmental trajectory in scholarly inquiry.

Perhaps the difficulty I am having is a reaction to the all-too prevalent push toward fixity in popular television criticism. NBC’s launch of Bionic Woman was preceded by a pre-air pilot that circulated on the Internet as a torrent after being screened at the San Diego Comic-Con in July 2007, while more than one blog was launched (or at least reserved) prior to the episode’s Comic-Con debut. Several months later, in September 2007, a reworked pilot (the series premiere) was made available at no cost through both Amazon Unbox (and its joint venture with TiVo) and various cable on-demand services. The attempt to fix meaning was set into action even before the series began its broadcast run.

Program blogs such as The Bionic Woman Blog and Watching Bionic Woman weave a complex intertext about fandom, stardom, and industrial discourse. As I pour over the efforts of a few bloggerati to claim the cultural relevance of a text that has not even aired, I’m struck by a gesture that simultaneously seems antithetical to the “populace” embedded in popular culture (as site authors sift through cultural detritus to construct an overly narrated and overly saturated meta-text) but also part of the very fabric of popular culture, endlessly decentering the text at hand and making it ever more porous. The problem of locating the text is part of contemporary television discourse, reflecting the fragmented nature of the broadcast landscape, scattered across multiple media platforms and viewing practices.

At the same time, however, Bionic Woman wears its cultural relevancy on its sleeve. The series premiere is quite self-aware, littered with observations about the laws of science and nature, and the physical and psychical tolls of warfare. A slide lecture on bioethics includes images of a victim of a Baghdad car bombing, and ends with a question about the threshold of intervention. Contemporary bionics is positioned as an aspect of military research and more pointedly as a tool to benefit casualties of the Gulf War, in line with the goals of real-world research undertaken by DARPA’s Revolutionizing Prosthetics Program.[1] Within this framework, the show’s central characters give voice to the narrative’s ethical musings, and shape science into melodrama. Sarah Corvus (Katee Sackhoff), the first bionic woman, voices a desire to cut away all of the parts of her that are weak; and Jaime Sommers (Michelle Ryan) learns that her relationship is built on a foundation of difference (brought to fruition by her technological makeover). All has not materialized as predicted in Donna Haraway’s manifesto on the cyborg. While a certain number of crossings are made manifest, and the cyborg myth of “transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities which progressive people might explore as one part of needed political work” is given form, why is the payoff in the series premiere one big chick fight?[2] Why are women situated as visible evidence to the dictum that science fiction is no longer purely fiction? And why are claims of difference temporarily overcome by hetero-normative coupling?

The relative success or failure of the program, not in ratings, but in the critical field, is partly about the answers to these questions. The problem at hand, as one begins to consider the role of bionics in the current popular imagination, is the degree to which speculation is already leading to certain foregone conclusions about the activities of the television text, while it still has yet to confront the uncertain resonances of any collision between fantasy and reality. The smell of desperation lingers in the fall air, as a number of industry players attempt to attach meaning to their products prior to their formal seasonal debut and far ahead of their first run denouement.

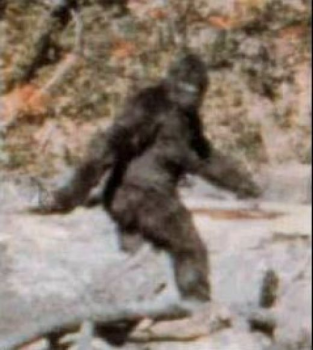

In his book, Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in Myth and Reality, author John Napier comments on the Patterson-Gimlin film of 1967: “One can hardly quarrel with a movie taken at a range of approximately 100 feet.”[3] Convinced that Bigfoot does exist, but never making a firm conclusion about the film shot by Roger Patterson on an expedition with partner Bob Gimlin, Napier muses instead about the status and claims of evidence. While I doubt very much that Bigfoot will stage a return in this season’s Bionic Woman, I am still intrigued by his very absence, a specter from the seventies that for me, at least, will linger over the reincarnated series. Fantasy programming in the seventies had a cultural value that was oftentimes overlooked, obscured by the overt presence of the absurd. Understandably, one can draw distinctions between products in the same genre that are aimed at decidedly different audiences; while Bigfoot’s appearance on both bionic shows of the seventies was a crossover bonanza, it was hardly a scenario constructed for adults. Yet as the signifiers become ever clearer, the metaphors less metaphoric, and the fantasy more proximal to reality (as the Gulf War gets written into the text), does the program become necessarily more useful as a climatological measure or simply more diffuse? What happens to reality as it gets embedded in a fantastic enterprise without play or irony? What statements are there to be made about our times, and what statements are still unspoken, signaled by the chatter of the bloggerati but never fully articulated? Napier asserts the value of proximity, which begs the question: How close should we be to our subject? At what point does it go out of focus again?

Notes:

[1]http://www.darpa.mil/dso/thrusts/bio/restbio_tech/revprost/index.htm

[2]http://www.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/Haraway/CyborgManifesto.html

[3]http://home.clara.net/rfthomas/bf_pgfilm.html

Image Credits:

1. 1970s Bionic Bigfoot action figure by Kenner

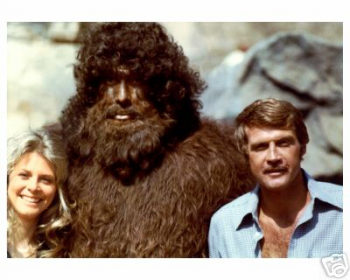

2. Lindsay Wagner and Lee Majors on the set with their Bigfoot co-star

3. Promoting Bionic Woman’s first showdown

4. Frame from the Patterson-Gimlin film

6. “Bionic Woman” Claudia Mitchell

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Bionic Woman » Blog Archive » Bionic Academia: Watching Bionic Woman Blog Cited in Academic Journal

Pingback: Graphic Engine » Blog Archive » Better, Stronger, Faster

Pingback: Graphic Engine » Blog Archive » Better, Stronger, Faster??