The Edwardian Country House: An Exegesis

by: Alan McKee / Queensland University of Technology

Sometimes, television producers are more intelligent, more informed, and present their ideas through more convincing forms of argumentation, than academics studying the same area. Take the example of The Edwardian Country House.

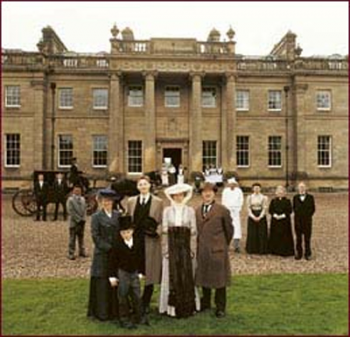

In this 2002 British reality series, 21 people live in an Edwardian Country House, just as they would have done in the first decade of the twentieth century. Six of them take the role of the family who own the house. Fifteen take the role of the servants. And they live those Edwardian lives – strictly – for three months. The servants have to get up before dawn, working all day for 120 hour weeks. They have no regular days off, and their behaviour is rigorously controlled by the housekeeper and butler. The family of the household are dressed by the servants, spend their days reading and relaxing, going out with friends, being fitted for dresses, and hosting dinner parties for politicians and other ‘great men’, for which, of course they do none of the preparation.

Produced for

We all have some understanding of what working class life was like in previous decades. We know the conditions of life for the poorer members of society were appalling compared with those in current forms of social organisation. To be working class now means to live longer, with better health, to be better educated, to have more control over all aspects of one’s own life, more free time and more choices about what to do in that time, to live in a more equitable world and to have more say in its running that at any time in the last four hundred years (to stick only to the period of modern Western history with which I am familiar). We know this – but all the same, to see it played out so vividly, and to see and hear what twenty-first century humans make of it, of living it – is a revelation.

In the final episode, the participants leave the house. There is passion, regret and sadness. The participants speak out about the experience as they leave. And what is inescapable is just how differently the two groups – the upper class and the servant class – feel about their time in the house, and what these differences in experience tell us about cultural change over the last hundred years.\

The servants – who in the real world hold working class or middle class occupations, who are shop assistants and secretaries – are clear. After three months of waking before dawn and working relentlessly until after dark, of having every aspect of their lives, including romantic relationships, work, pleasure, eating, and sleeping, routinised, scrutinised and controlled by authority figures, with no regular time off and no control over any aspect of their lives – after this, the working class participants are desperate to return to the twenty first century.

Antonia has been the kitchenmaid in the Edwardian House – in 2001 she’s a telephone operator in a police emergency room. As she considers leaving, she notes: ‘Here you can’t vote, you can’t speak to who you want, go where you want, just everything’s cut off, all the options we’re open to, they’re just not in existence, you think, gosh, you know, we’ve come a really long way since then’. Rebecca, the first housemaid (who works in tourist information in the real world), is amazed at just how hard servants had to work, compared to the working classes in the twenty first century: ‘My grandma was in service… I just thought, how could she have worked that hard that she [literally] wore her fingers down? And now I know how’. Rob the footman (currently looking for work) notes that: ‘Since I’ve been here I’ve lost 22 pounds. The food is enough for sustenance, but that’s all. If you’ve got a bit of a health regime you’ve just got to throw it completely out of the window’. Charlie, also a footman (sales manager) delights in regaining the simply physical freedom of movement, rejoicing in being able to sit outside to eat his lunch – which he has not been allowed to do for three months. ‘Rob and I have got a little room, and it’s ever so tiny, with our little straw mattresses, and we don’t get a wall, we just see a bit of wall about four feet away from the window, and occasionally we’ll see daylight for about two hours a day’. For all these people there is no question – they desperately want to return to the social and cultural forms of the twenty first century.

But what is really interesting is the perspective of the upper class as they consider leaving. John Olliff-Cooper – in the twenty first century a business owner, in the Edwardian era, the Lord of the house – is deeply upset. ‘It will be heartbreaking to leave’, he says. ‘The only people who will be diminished when they leave are my wife and I’. And Anna Olliff-Cooper – a doctor in the twenty first century, Lady of the House in the Edwardian version – is rueful. ‘It is one of these eternally difficult questions’, she says as she stands on the steps of the house where she has lived in luxury for three months. ‘If you level everybody out to the same level, you remove some of the highs of life. You also remove the lows. And I suppose each person has to make up their own minds about what they think is fair. You might think that in Edwardian times it was skewed too far one way. You might think, in fact, it’s skewed too far the other way now’.

It’s an arresting moment. It’s rare that you hear a voice on television explicitly claiming that democracy has gone too far … that people are treated too equally … a sense of nostalgia and loss for an era when hierarchy was more entrenched and servants laboured to provide the good life for the wealthy.

What this moment, and this program, makes clear is that cultural change has been good for some people and bad for others. For the working classes, it has clearly meant a huge improvement to their lives. To the upper classes, it has meant a massive loss. I think this is an important point. And it’s a point that academic writing has often forgotten or suppressed.

Academic analysis of cultural change tends to be stuck in a binary model – as I discuss in my book The Public Sphere (Cambridge University Press, 2005). Either you take the position associated ‘modernity’ – things have got worse, the public sphere is disintegrating, public culture has lost its golden age – or the ‘postmodern’ position – things have got better, public culture has become more open and thus improved. It’s a sterile debate, neither side ever managing to convince the other of its point of view. The producers of The Edwardian Country House offer a more nuanced, convincing and better researched position – that it depends on which social group you’re talking about. For the working classes, things have undoubtedly got better. Also for unmarried women of all classes. But for married upper class women, and upper class men, they have got worse.

These points are made in visceral, powerful and confronting ways. In order to keep upper class culture untouched, we must sacrifice the lives, the health, the sanity of the vast majority of the population who are not in that class. We see the servants trying to cope with these lives – the tears, the physical and emotional pain that they suffer. And we see the joy that it brings them as they appreciate just how much better life is now. Eva Morrison, the lady’s maid (in the twenty first century, a haberdashery shop owner) is strongly feminist, and throughout the series we see her reactions to reminders of just how much women were oppressed in the early twentieth century, and how far their rights have come in a hundred years. She reads the Daily Mirror from the 4 June 1913: ‘Woman rushes on the

I have often wondered how academics can look back at the cultural and social change of the last few hundred years and see it as a decline. I can see how it would seem that way for the upper classes – but how could the massive improvement in the lives of working class people be invisible in theories about public culture? And The Edwardian Country House is such an intelligent piece of filmmaking that it proposes an answer to even this question.

Because of the way the hierarchy is managed, the upper classes think that everything is OK with the system – that it works for everybody. And this is because it is purposefully set up in order to protect them from seeing the reality of the working class experience. The family live in the house for three months and never see the servant’s quarters until the once-a-year servants’ ball – just as would have happened in the real world. The butler – along with the housekeeper one of the two people who act as the interface between the worlds above and below stairs – ruminates on this quite explicitly. On the final day, as the family say their final farewells to the servants, tears falling down their cheeks, the butler’s VO provides a commentary: ‘I knew the family to be genuinely fond of the staff, even though they did not really know them. When I have problems downstairs, I shield them from them. I never tell them. So what they hear always is the nice moments. So they do become fond of them. I don’t think that fondness is reciprocated towards the family’. And indeed, we’ve seen a bonfire where the servants made the guy in the shape of sir John, cheering as it burned to death. This perhaps is how it is possible for academics to genuinely believe that the cultural and social changes that have elevated working class citizens have been a form of decline – because the representations of working class life that were available to educated writers in the past deliberately misrepresented it. The system was set up so that the educated classes would have no knowledge of just how awful working class existence was, and to maintain the fiction that everyone was happy, that the system worked for everybody. The Edwardian Country House systematically and powerfully demolishes that fiction for us.

Which brings us back to where we started. Sometimes, television producers are more intelligent, more informed, and present their ideas through more convincing forms of argumentation, than academics studying the same area.

Image Credits:

2. Becky, the first housemaid.

3. Sir John getting a shave from Edgar.

Please feel free to comment.

Alan,

Which amount of nostalgia fits in all of this Edwardian reenactments?

Thanks,

tchouaffe

Not sure I understand what you mean? Are you getting at the question of whether the program itself is informed by nostalgia? In which case, it depends how you define nostalgia. If you mean, an interest in the past, then yes. If you mean, a romanticization of the past, then expressly no – that’s what I was getting at with these comments. It romanticizes the past much less than many academic commentators who mourn a lost ‘golden age’ of culture before ‘dumbing down’, ‘trivialization’ and ‘reality television’!

There are large subtexts to the Edwardian House that cannot be simply address in one Flow column. I was equally referring to the Edwardian House and certain notions of English nationalism, masculinity and Empire. Some of the violent manifestations of English Hooligans in football stadiums across the globe have often been attributed to this lost of the “Golden Age”. I do not know if you see that as a stretch.

Certainly, nostalgia for various ‘golden ages’ has been mobilised to explain everything in the modern age – from declining levels of literacy (!) to the loss of ‘values’ and increasing tolerance for homosexuality, etc etc etc.

Are people idiots?

I recognize that this is both a bit harsh and an abrupt generalization about the people on Edwardian House who were “chosen” to live as the wealthy family rather than as the servants. But really, did these people even think about the labor their “staff” went through on a daily basis? It’s almost absurd that in this day and age, people can still so willingly turn a blind eye towards the labor of others.

My use of the word “chosen” above is deliberate, for while I imagine wealthy families in the Edwardian period did indeed believe themselves to be “chosen” for their easy lifestyle (perhaps out of some misguided sense of being deserving), those on the TV show should harbor no such illusions, for they were cast for a constructed-reality television show. It was chance; they could have as easily been servants or not involved at all. Such is the nature of life. How interesting that by the end of the show, those lucky enough to be in their position of false power should have forgotten how arbitrary it was that they should be there at all.

It’s an interesting point, Katherine. As the butler pointed out, a large part of his work involved making sure that the family *didn’t* get any sense of the reality of life below stairs. All that they got to see was the jolly stereotype of the happy servants, working hard but enjoying themselves, with a genuine community and great friends …. etc etc etc.

I wanted to scream (since I couldn’t smack her in the mouth)when the lady of the house was talking about how wonderful life was in the Edwardian age. When they wanted to have a dinner party for fifty people it was so easy. It was just fun. Sure, because she didn’t have to do any of the work. The blindness of the upper class family was appalling. Yes, they are suppose to play the part of extremely wealthy people but they actually turned into those people. They should have been aware of the work it took to keep that house running and should have had some idea that the staff was too small. A house that size would have had a lot more people working there. And the most pompous jackass who believed he deserved his position, who wanted everyone else to play their parts exactly but didn’t think that applied to him when he didn’t like something, Sir John actually said he had no ego at all. He said his staff was very happy although he’d never asked anyone if they were. In fact he hadn’t met them. And weeping because he has to leave and won’t be waited on hand and foot. What a fool. And I’m not too sure I’d want his lady wife as my emergency room doctor. I hope they watched the program and realized what kind of people they really are.

I think this is one of the best documentary series I’ve ever watched. I have a very difficult time articulating what I am feeling after having watched this series. I laughed with them, I cried with them, and I felt every other emotion with the cast. It was so interesting to watch the casts real 21st century lives fall away as they were caught up living their everyday lives in the manor. This just goes to show you how societies or social norms are created and perpetuated to some extent. So many times 50 years of living I have heard, in various television broadcasts, people say “I think I would like to go to America to start a new life” and now this statement has really hit home for me… I get it. There’s so much going through my thoughts that I can’t possibly put them all to pen.

I can’t help but keep wondering about the cast and their lives now. I would love to see a short follow up interview, now, with each cast member to hear their reflections on the experience of living this period and how it has affected the way they think and now live their lives.

I thank the ALL of those who were involved in creating this experience for the viewers.

I totally agree with a comments of Sandra Molnar. While I enjoyed the show very much, I was appalled at the pomposity of those playing the family. I could have not kept up the charade for three months of treating people with such utter disdain. Milady’s comments at the end of the ball episode, were said with absolutely no regard for how hard the servants had to work so that she could enjoy herself. I understand that they wanted to stick to the Edwardian script but like I said I could have not treated treated people so abominably for that length of time and how easily they fit into their roles except for the sister. I would love to know how they treat others in the 21st century!!

I am slow. I just saw this series and perhaps I missed it but to me the glaring reality was the grotesque economic inequity and abject poverty that allowed for the “Edwardian” – and many other periods – culture. The poor had no alternative but to accept the harsh working conditions. We may look at our current march to equally grotesque inequity, weakened labor movements and treats to women’s control over their own lives to understand why the “ruling” class so dedicatedly are working to replicate the era for themselves. Get your scrub brush ready.

I have read that the Olliff-Coopers divorced. I wonder if the series showed traits which the wife disliked about the husband. It was reality-television, which so interestingly and surprisingly became very real to them. The husband acted his part appropriately—but seemed to be convinced that he deserved that life in real-life. How great, it would have been, to switch roles with the same “volunteers” in a subsequent season.

It would be very interesting to do a ‘where are they now’ as a 20 year commemorative show. Either real interviews or just third person updates on each cast member.