Sanjaya and the Mulatto Millenium

by: Mary Beltrán / University of Wisconsin-Madison

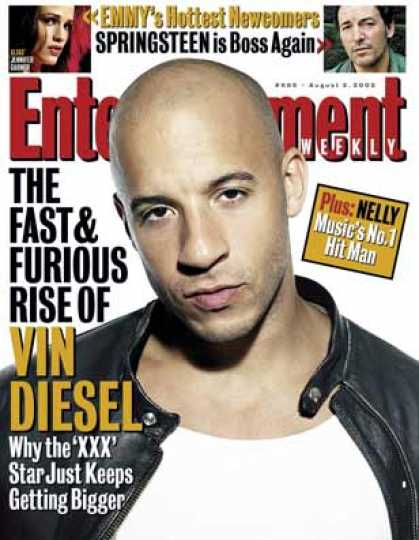

As Camilla Fojas and I note in our forthcoming anthology, Mixed Race Hollywood, we have embarked on a new era. (Fojas is credited as co-author of this opening paragraph, adapted from the book’s introduction). As novelist Danzy Senna succinctly describes it, we’ve entered the “mulatto millennium.” This certainly seems to be the case if you follow trends in popular culture. If you turn on your television you might happen upon mixed-race actors Vanessa Williams in Ugly Betty (2006+), Wentworth Miller in Prison Break (2005+), Kristen Kreuk in Smallville (2001+), or models of various mixed racial backgrounds competing to be declared America’s Next Top Model (2003+). Similarly, you might see Vin Diesel, Keanu Reeves, or Rosario Dawson’s latest film at your local multiplex, hear Mariah Carey talking frankly about her mixed heritage on a talk show, or read about Raquel Welch “coming out” as half Bolivian. In truth we’ve always liked mixed-race performers (think Nancy Kwan, Anthony Quinn, and Freddie Prinze, Sr.), but these days it’s a boon to star hopefuls not only to have an ethnically ambiguous look but to be open about their mixed heritage in their publicity.

Entertainment Weekly cover

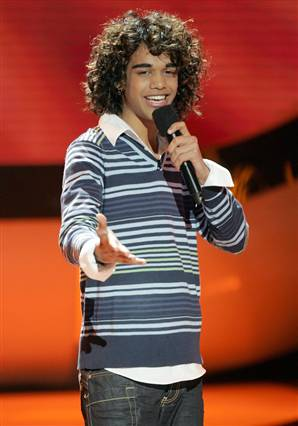

A recent illustration can be seen in the massive popularity of ex-American Idol contestant Sanjaya Malakar. Even while he was in equal parts adored and maligned by viewers and the Idol judges, he achieved a level of fame and attention in the entertainment news media unsurpassed by any other non-winner to date. On a recent perusal of a newstand I noted that Malakar was featured in several major U.S. entertainment and news magazines—even People, which featured Malakar on its cover in a small photo insert captioned “Sanjaya Tells All!” This is not to argue that the 17-year-old performer has become popular merely because of his dual Bengali Indian and Italian American heritage. Clearly Malakar’s personality, charisma, and potential as a performer are largely to credit for the stardom that he garnered during his stint on Idol. But I would argue that the singer’s mixed background and ethnic, but not too ethnic look, also played a role in his capturing the hearts of many viewers.

Sanjaya Malakar singing

People’s “tell all,” among other things, answers the puzzle of Malakar and his sister Shyamali’s mixed heritage, given that viewers already had seen his sister and his mother, Jillian Blyth, cheering him on each week. We learn from People that Malakar has an Indian father, Vesuveda Malakar, a musician, and that his parents divorced when Malakar was 3 years old. Notably, pictures of Sanjaya and his Italian American mother and of Sanjaya and Shayamali as young children are included among the illustrations that document Sanjaya’s life as a mixed-race youth for curious readers. His story is one that I would argue is increasingly coded as American in star promotion efforts. While it isn’t why he became popular, it has helped that Malakar not only has the right look at the right time, but also a life story that is timely and compelling to the U.S. viewing audience.

Sanjaya Malakar

Sanjaya’s charm notwithstanding, why are we so enamored of ethnically ambiguous, mixed heritage individuals? In part because of the ongoing evolution of ethnic demographics and identity our country. Americans, and particularly the youth generation, have never been so racially and ethnically diverse as in recent years. In addition, the numbers of mixed-race families and youth have boomed since the 1970s and are projected to continue to grow. A broad perspective on ethnic differences therefore could be expected to come naturally for many of the Millennial Generation, the first generation large enough to displace the Baby Boomers in dictating the direction of popular culture. Advertising and other studies have shown that youth and younger adults today are more culturally curious than their older counterparts, demonstrated in an interest in television shows, films, and other pop culture forms featuring individuals perceived as non-white. As the rise in mixed-race actors and performers attests, however, we can’t necessarily shake the standards of beauty that have been drilled into us by a century of white-centric media culture. Actors, models, and others in the public eye who can embody the “ethnicity lite” that enables us to have it both ways—for example, Jessica Alba, Keanu Reeves, Vanessa Williams, and Sanjaya Malakar—are seen as especially attractive today, and are increasingly successful. While only time will tell if Sanjaya’s fame will extend beyond the shelf life of this most recent season of American Idol, this trend in popular culture arguably is only beginning to be felt.

Image Credits:

1. Entertainment Weekly cover

2. Sanjaya Malakar singing

3. Sanjaya Malakar

Please feel free to comment.

I must admit that most of my pleasure in watching the first season of the L Word had to do with the Kit/Bette mixed race, half-sister storyline and the exploration of their relationship with their father. While representations of mixed race characters have increased, it still seems that familial relationships or even representations have been largely left unexamined. For instance, I also very much enjoyed Miranda July’s Me, You, and Everyone We Know, in part, for it’s representation of a mixed race family–in spite of the fact that they were splitting up. It’s still so rare to simply see a mixed race family in film or television that I might just be clinging to what I can get (although I do want more than Joy, Crabman, and their children in My Name is Earl!).

I wonder if it’s not only a generational aspect at play amongst audiences’ increasing acceptance of mixed race celebrities, but also a generational aspect amongst the performers themselves. Or can we even separate the two proceses? I don’t recall (and I am making a very speculative assumption here) individuals like Halle Berry, Mariah Carey and others celebrating their ethnic heritage. In these instances, particularly the latter, it seems that they instead perform one or another aspect of their ethnic identity when it benefits them the most.

this is a topical issue – especially in identifying a shift from what was known, at least in some traditions, as the “tragic mulatto” to “mulatto as the american idol.” a couple of things come to mind though, one, what about Sanjay’s alleged “lack of talent”? Is the buzz just about his hair-styles or about displaying america’s ‘multiculturalist’ face?

Following up on Dada’s comment, Sanjay’s “lack of talent” seems familiar to fans of multiple other mixed race celebrities including the above mentioned

Jessica Alba, Keanu Reeves, and Vin Diesel. Indeed, the pantheon of multiracial celebrities appear to be split between the tragic and talented (Halle Berry and Mariah Carey) or the happy and talent-free. I’d like to suggest that the dismissal of some of these celebrities is linked to a perceived lack of authenticity that follows many multiracial figures.

As a member of a multiracial family, I have reason to cheer the increased media presence of people of various mixes, from Sanjaya to Obama to Keanu, but as a scholar with historical perspective, I also must remain, if not cynical, at least skeptical. For instance, the buzz among some white about Obama “transcending race” sounds like an escape clause that allows whites to avoid talking about race. I also wonder about whether this latest round of multi-fetishism isn’t just another flavor of exoticism. Also, we have to ask whether the appeal of these white-other mixes isn’t in part the white side of the equation — they’re sexy because they’re not “just black” or just whatever else they might me. We could be heading toward a Brazil-style multi-leveled hiearchy, with totally white at the top and totally black at the bottom. Also, what about mixed people who aren’t as cute as Halle Berry or Sanjaya? Does cuteness somehow grant you permission to be multiracial? What happens if you happen to be mixed, but have acne scars, a million freckles, elephant ears or thunder thighs? Then there’s the crucial question of whose discourse is working in the discussion of multiracials. To quote Heather Dalamage in “Tripping Across the Color Line”: “Because they do not quite fit into the historically created, officially named, and socially

recognized categories, members of multiracial families are constantly fighting to identify

themselves for themselves.” From Bakhtin’s perspective, we might call this the struggle for internally persuasive discourse. Now, Dvora Yanow, in “Constructing “race” and “ethnicity” in America: Categorymaking in public policy and administration.” : ” … the federal government only makes available some categories of hyphenated-American for people to use in telling their stories, … “Being unable to do so [use your own categories] calls into question one’s membership in American society.” Here we have the struggle with authoritative discourse. Mere visibility isn’t enough to celebrate. After all, African Americans have been very visible in sports and entertainment for decades, which has been a mixed blessing. The ultimate question is, “On whose terms are we visible?”

“it seems that they instead perform one or another aspect of their ethnic identity when it benefits them the most.”

Or maybe, not because it benefits them the most, but when either constructed identity is assumed or imposed by others. I saw an interesting interview with Halle Berry on Parkinson where she mentioned she felt at odds because being black could be a major casting barrier, but at other times, she wasn’t black enough!

I think all of the above comments are valid. The visibility of mulattos (I’m one myself) is in part a natural outcome of demographic change (one would think) and in part a hint of exotic. As long as one is cute of course, but when is that not the case? And yet, as mentioned, so few mixed-race families, only ambiguous individuals..

On a practical level at least, actors with mixed heritages might have a little casting advantage when it comes to flexibility. Or they might just get typecast as the token ethnic person. I remember a while back a bit actress I kept recognising around my telly, here a muslim, there of ambiguous middle eastern origin, and then latino.. No kidding!

It strikes me that mixed race performers like Sanjaya strike a chord in the mainstream because of the “safe” way his ethnic features are blended with conventional white versions of beauty – small, narrow noses, lips that are full (but not TOO full), skin tones that are just colourful enough to connote difference without shouting it. Celebrating this kind of “enlightened” beauty lets white viewers feel open-minded in a non-threatening way.

But more than this, the kinds of mixed-race faces and bodies that are catapulted to stardom are often culturally de-ethnicized. They don’t speak much about any customs, holidays or beliefs that the mainstream may find puzzling or worrisome. They can’t seem too different from the mainstream. And they don’t openly celebrate any connection to the ‘hood or the bario.

In my five years living in the US, I was often amazed at how Americans tend to conflate race and class in pop culture. There is little popular discourse about class, so it all gets folded back into discussions about race. It would interesting to look at mixed-race celebs from a class perspective. I didn’t see the People mag article on Sanjaya, but I’d wonder if it played up his middle class credentials.

Pingback: An Eye for an Eye: Remakes and RepressionJanani Subramanian/University of Southern California | Flow

Pingback: Journal Articles – Mixed Up Online