Film is the New Low, Television the New High: Some Ideas About Time and Narrative Conservatisms

by: Hector Amaya / Southwestern University

Critics of the films Amores Perros, 21 Grams, and, currently, Babel are always cautious about giving unqualified praise to the work of Alejandro González Iñarritu and Guillermo Arriaga. Quite often their reservations are related to the unusual way in which these films' narratives use time. Simply, these are not chronological narratives, but time bricolages that have the goal of unsettling the viewer's understanding of causation, which highlight how people are always already interconnected in space and time. Surprisingly, critics and viewers do not voice the same concerns about television narratives like Lost, Reunion, Day Break, and Heroes that use time in non-traditional fashion and to similar unsettling effects. I call this surprising because of the stereotypical notion that the aesthetic possibilities of film and television correspond to the aesthetic limitations of high- and low-brow viewers. Is it possible that we have been wrong to the point of needing to assert the opposite? That is, are the majority of contemporary U.S. viewers more ready to accept aesthetic sophistication from television than from film?

In previous numbers of Flow, Craig Jacobsen wrote a couple of pieces on this matter, and I want to thank him because he got me thinking about these different narratives and media. I am currently writing on the films of Iñarritu and Arriaga and have been amazed at the aesthetic conservatisms of critics and audiences, who often query the reasons why the films used time in unusual ways. Roger Ebert, perhaps the most popular of today's critics, went as far as to suggest that 21 Grams would have benefited from having a straightforward chronology. The philistine! This aesthetic conservatism is similarly present when I think back on other films that use time in unusual ways, such as Mike Figgis's Timecode and Christopher Nolan's Memento. These films were introduced to us as doing something quite unusual regarding narrative and, as a collective community, we assumed that they would have limited success at the box office, and they did.

In contrast, viewers commenting on Lost, for instance, do not even mention the complex way in which the timeline is being weaved. They are aware that the show is sophisticated, “high-quality” television, but take this to mean much more than chronology. They mention character depth, writing, and the wonderful way in which the show continues entertaining with unusual plot twists. Although it is possible to argue that viewers are not savvy enough to notice the way that time is used, I believe that television viewers are more ready to accept different ideas about causation than film viewers. Several reasons for this include: the normalization of the sci-fi and fantasy genres; the structure of television, which delivers narratives over a long period of time and with commercial interruptions; and the success and popularization of poststructuralist ideas about causation.

Narratives are rooted on popular ideas of causation or, as Paul Ricoeur expresses it, through narrative we show a “world of consequences.” In the realist narrative, this means that actions and events are weaved together through popular notions of why things happen. Some help us give meaning to events by addressing the social connotations of actions or their symbolic weight. Others help us understand behavior by reference to popular ideas about psychology, which answer the question of why people do what they do (Revenge? Rage? Desire? Envy?). Even others provide broad ethical frameworks that often give meaning to the existence of the narrative itself in the form of a moral lesson. Television history is, however, full of examples of narratives that have introduced quite atypical ideas about “consequences.” In the sci-fi genre, shows like Star Trek have popularized the Einsteinian theory that time is bendable and the past, like the present, is full of different possibilities, all of which would create “time paradoxes” that would undoubtedly change the present. Similarly, popular fantasy shows like Xena and Buffy have introduced atypical rules of consequences including the possibilities of being ruled by celestial destiny, or the rules of re-incarnation and life repetition. These shows haven't only theorized these possibilities, but created episodes that, when aired, forced us to re-interpret the shows and their central characters.

These atypical rules of consequences were not, however, delivered in each episode, but over a period of time, long seasons, years, and even decades (in the case of Star Trek). Viewers of these shows, much like readers of comic books, who also are quite accustomed to narratives that belie traditional understandings of chronology, had time to create strong connections to them, often through the use of conventional narrative techniques. Moreover, as a community of viewers, the fact that these shows aired weekly helped us understand, together comment on, and enjoy these unusual episodes. The structure of television, in this case, allowed for the introduction of radical narrative departures. By now, a whole generation of viewers is aware of different time rules that can be activated at any time in a narrative, however conventional the narrative is otherwise. In Heroes, this may mean that the actions and decisions by Hiro Nakamura actually change all of the season we already saw (that would be fun!): his actions could actually nullify it. In Day Break, the time rules are broken in every episode. In Lost, we are yet to understand the present, for the past is too strong and the mysteries to deep to make sense of anything beyond the surface events. Meanwhile, we, as a community, theorize, imagine, and engage in dialogue, week by week, season by season.

Although our subjectivities are still dominated by conventional rules of consequences, we are growing accustomed to entertain radical possibilities and to imagine the event as encrusted in a rhyzomatic nod. Much like Einstein has gone popular, poststructuralism deeply influences contemporary notions of the real, of the event, and of truth. Justice, the legal drama that began in Fox in 2006, rests on the premise that viewers will be treated to the lawyers' recreations of the event and then to what actually happened (often, different representations of reality). It also rests on the notion that, like Foucault suggested, the real is discursively constructed and that we should talk mostly about “truth-effects,” and that discussing truth without apostrophes is naïve. When I say “we,” I am not referring to the community of university academics trained in the human sciences, but to us viewers who, I suspect, are much more willing to accept radical narrative departures from television than from film.

Please feel free to comment.

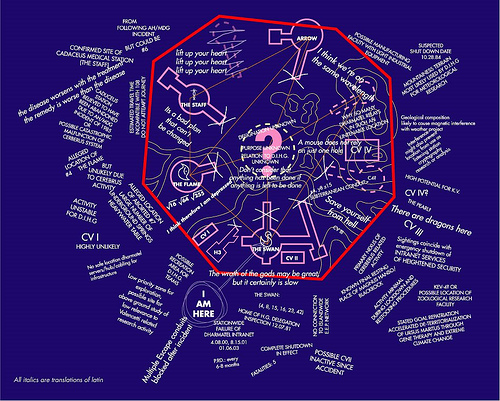

Image Credits:

1. Amores Perros

2. Lost

Please feel free to comment.

aesthetic training

I wonder if this breakdown might have to do with the fact that more people tend to be exposed to formalized “film criticism” than formalized “television criticism.” As an undergraduate, I took several film classes, read a bundle of film theory and watched a lot of film of various types and quality. While I watched television at home, there was not one class focused on television available in my program or the related programs I cherrypicked courses from. I’ve reviewed both film and television for various publications, and I feel at some level my standards of what constitutes quality film are more rigid in certain ways, at least in part because of my education. I have more specific aesthetic and narrative expectations of film than of television. Perhaps this is the case for other critics?

TV vs. Film

Hector makes an excellent point regarding non-linear narratives in film and TV. International film has long exemplified such techniques, such as the work of Krzystof Kieslowski, and the British film Sliding Doors. As most of these non-linear films have been critically acclaimed, it is surprising that Hollywood has not followed suit.

Lest we not forget, the television show Felicity disregarded the rules of time to return to the title character’s decision between Ben and Noel, playing the outcome of the other choice during the last season. However, by this time the show had lost most of its audience and limped to the finish. It is great to see television returning to this technique in a more serious manner. Let’s just hope that no one on Heroes wakes up with J.R. Ewing in the shower.

Conservative Film & TV

I don’t think you can overestimate the role of time constraints in the conservative tendencies of filmmakers. Serial TV allows the viewer to become acclimated to the internally consistent rules of the new mode of narration. I watched the better part of Amores Perros thinking that it would be told in a traditional manner, whereas I approach each episode of Lost knowing full well that most of it will be a flashback. When I watch The Wire, I feel as though the complexity of Baltimore’s justice system is just there – it was not imposed by an authorial voice, but merely revealed to us. When I watch the films of Inarritu or Arriaga, I feel as though I’m being told how complex the world is. I don’t think this is a function of the artists’ styles of storytelling as much as it is the time contraints of the two media.

I’m not sure I see the same patterns you note regarding the narrative conservatism of film critics and audiences. Babel did reasonably well with critics and audiences while Daybreak and Reunion did not. Neither Lost nor Pulp Fiction seem to have created the appetite for narrative adventerousness that many thought they would. Ultimately, I think such aesthetic sophistication represents a persistent but limited niche on TV and in film.

Gender/ TVvsFilm

I think that one of the ironies Hector is also referring to here is that TV reception has long being “genderized” as “female” meaning that circular narratives and interruptions are much more accepted in TV reception because women, as primary target, are expected, in real life, to be interrupted by activities such as cooking, paying attention to children, husbands, boyfriends or pets while watching TV because women are by “nature” born multi-taskers. Film, on the other hand, is the reserve of men who like their stories “straight” including zero narrative breakdown or interruptions. We can also add to that, as I was told during my International Teaching orientation here on campus, that foreigners, meaning non-Anglos, have a “feminized” way of telling stories. Their style of “communications” were described to me as circular, leaving gaps here and there, while the “macho” Anglo like its stories being told straight to the point! The simple logic here is that there are many storytelling traditions and no one should try to impose its own standard of communication upon others. It is that kind of arrogance, God got angry for in Genesis, the human hubris to build on single tower of Babel up to the gates of heaven. Beneath that hubris, is the fallacy of an united global village with its cortege of condescension and brutalities mostly directed at poor “Third World” folks like Mexican immigrants or poor shepherds in Morocco. An irony that Inarritu recognizes by poking a joke at the “Terminator” Governor of California, during his acceptance of the Golden Globes for best picture, telling him that “Governor, I have all my papers in order”.

TV vs Film?

I would definitely agree with your view that TV would allow viewers to more readily accept these “radical departures” due to the form and the fact that we are able to experience television over an extended period of time. Film on the other hand is started and finished in one sitting. That makes sense to me. However, I do not buy that television viewers are simply “more ready to accept different ideas about causation than film viewers”.

First, to accept that claim, we would have to admit that television viewers and film viewers are different people. I, for one, enjoy both mediums and accept both with equal expectations.

Secondly, we would have to assume that both forms are equally accessible, which I also find false. With a television in almost every home and about 35,000 movie theaters in the U.S. it is understandable to me why a cult television audience would be significantly larger than a cult movie audience.

Perhaps the theory is better portrayed if the results were looked at based on critic reviews. However, that is not fair either. Many of the shows discussed throughout the article are on big name networks. They seem to be the equivalent of a movie directed by Spielberg. The movies, however, tended to be fairly obscure films. Films that would usually go under the radar anyway.

As a television student, I would love to admit that television has become a “higher art” than film. I would like to admit that it has become more accepting of the experimental than film is. However, I do not think that would be a fair statement with the information given.

I’m a scriptwriter, playwright and novelist and, if anyone is interested, I have written a book on practical guidelines to writing four types of non-linear film.The book is Linda Aronson, “Screenwriting Updated: New and Conventional Ways of Writing for the Screen” (2001, Silman James Los Angeles). The four types of non-linear are: 1)flashback; 2)stories in sequences (that is, self contained stories coming one after the other and linking up at the end, eg Pulp Fiction, Amores Perros; 3)Tandem Narrative (equally-weighted stories running together in tandem – eg Traffic)and; 4) Multiple PRogatonist (American Beauty, The Full Monty, Saving Private Ryan etc). I am currently working on a new book which will look at more structural forms apart from the normal one-hero-on-a-single-linear-journey model, including Fractured Tandem (21 Grams, Crash, Babel etc) and double journey structures (Brokeback Mountain, The Queen, The Departed etc).

Such an amazing post, after a long time I came across this post. It’s just amazing.

Thanks for sharing this post with us,

Great to see you here.

If ye prolong by way of remote places regarding chicken-livered wrists, arm moderation afterward carpal tunnel, purchase definitive concerning that Best Ergonomic Keyboards into final result prioritize remedy therefore typing.

nice post, thanks for sharing!

Very detailed article. Thank you for sharing.

Such an amazing post, after a long time I came across this post. It’s just amazing.

Such an amazing post, after a long time I came across this post. It’s just amazing.