Rap Is Not a Luxury in The Forty-Year-Old Version

Christina N. Baker / University of California, Merced

The words of Audre Lorde, “poetry is not a luxury,” resonate as I reflect on Radha Blank’s The Forty-Year-Old Version (2020). For women, Lorde writes, poetry is “a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.”[1] Poetry is “a disciplined attention to the true meaning of ‘it feels right to me.’”[2] The Forty-Year-Old Version offers a novel perspective on creative expression that reflects Lorde’s timeless testament to the power of the poetic to name the truth of what is felt.

The Forty-Year-Old Version is a semi-autobiographical narrative feature film, written and directed by Radha Blank (winner of the Directing Award at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival). Blank stars in the film as a fictionalized version of herself—an award-winning playwright named “Radha” who finds artistic fulfillment and empowerment through hip hop as she approaches the age of forty. In The Forty-Year-Old Version, rap is the poetry that is vital to Radha’s existence. Rap is an expression of what feels right to her.

When we meet Radha, her career as a playwright has become financially and emotionally unrewarding. She supports herself financially by teaching a playwrighting class to high school students in Harlem. As one of her students bluntly puts it, Radha’s career has stalled “’cause white people scared of the truth.” Soon after, as an exemplification her student’s supposition, Radha has a distressing and maddening encounter with a white theater producer, J. Whitman, who Radha characterizes as having a penchant for producing “Black poverty porn.” When she describes her play about a Black married couple living in Harlem, working to keep their business afloat in the face of the gentrification of their community, Whitman’s reaction is “That’s it?” Her play—her vision—does not fit his vision of Harlem. He wants to see a Harlem of gunshots and rapping teenagers. And, by the way, she needs to add a white character because they “need to grab the core audience,” he later informs her.

Must Radha compromise her artistic vision? This tension between art and capitalism, particularly for artists of color, is highlighted in bell hooks’ essay “Back to the Avant-Garde,” in which she states, “I am acutely aware of the way in which our longing to experiment, to create from a multiplicity of standpoints, meets with resistance from those whose interest in that work is primarily commercial.”[3] J. Whitman views Radha’s play through a profit-driven lens and, as Audre Lorde warns in “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” “within living structures defined by profit…our feelings were not meant to survive.”[4]

“I just want to be an artist,” Radha cries, as she sits alone in the darkness of her apartment, sobbing and pounding her pillow in frustration after her artistic vision is discarded by J. Whitman. Radha’s plea to be an artist is not a capricious desire. It is a need to fully express herself. In that moment, the vulnerability of her emotional state creates space for her to feel, in the words of Audre Lorde, “an incredible reserve of creativity and power, of unexamined and unrecorded emotion and feeling”[5] that had been hidden. As she sits in her apartment, she hears hip hop music outside. Although the song she hears (comically titled “Pound da Poundcakes”) represents the epitome of commercialized, hyper-masculine, hyper-sexualized rap, hearing the music at that precise moment sparks something inside of Radha. She lifts herself up, faces herself in the mirror, and the words begin to flow.

In Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop, Imani Perry analyzes the artistry and poetry of hip hop as an overwhelmingly and fundamentally Black art form. Perry explains that rap is a “mixed medium” that merges poetry, prose, song, music, and theater.[6] As “prophets,” rap artists are adept and nimble poets whose words reveal the truths of their experiences. The commercialization of hip hop has certainly altered the art of rap, acknowledges Perry and other scholars, yet it has not obliterated the practice and possibility for the lyrical poetry and truth-telling that is the basis of rap as an art form.

For Radha, rap is an art that she can engage without the pressure to compromise her voice for others. Although there’s no question that hip hop music has been expanded and commodified beyond its roots in Black communities, for Radha, rap is an opportunity for artistic relief and release. It is about freedom of expression more than commercial or critical success. When she meets with her agent, Archie, the day after her revelation, she tells him “Think about me doing hip hop.” Surprised and confused, he replies, “Doing what to it?” She tells him that she wants to make a mixtape about the 40-year-old woman’s point of view.” Rap “is about creating something that is mine,” Radha tells him, “something that doesn’t rely on critics or gatekeepers.”

Radha’s poetry flows organically from a place deep inside. She raps about what she knows—about her truth. At first, in her apartment, she raps about the bodily changes she experiences as a forty-year-old woman with honest and, often, humorous lyrics like “Why my ass always horny? Why I always gotta pee? Why the young boy on the bus offer his seat to me?” When she goes to a studio to record her mixtape, she explains that she’s been working on a social commentary about “the white gaze’s eroticism of Black pain.” Her lyrics are inspired by her experience as a Black playwright in spaces that are culturally and structurally defined by whiteness:

No happy Blacks in the plot lines, please

But a crane shot of Big Mama crying on her knees

For her dead son, the B-ball star who almost made it out

Sounds fucked up enough to gain my film some capital

So I’mma pitch some fucked up shit made just for the screen

The most pathos-drenched story that’s ever been seen

Sure, Blacks be having Huxtable achievements

But these white producers just don’t be believing shit

Yeah, it’s poverty porn. I’ll write some poverty porn

Yo, if I wanna get on, better write me some poverty porn

“Our poems formulate the implications of ourselves, what we feel within and dare make real, our fears, our hopes, our most cherished terrors,” writes Audre Lorde.[7] Rap is the poetry through which Radha dares to make real what she feels, fears, and hopes. She raps about her embodied experiences as a forty-year-old woman. She raps about the frustration and anger of her voice being policed and exploited for “poverty porn.” She raps because it offers her the freedom that has been out of reach in other areas of her life.

As Lorde explains, “If what we need to dream, to move our spirits most deeply and directly toward and through promise, is discounted as a luxury, then we give up the core—the foundation—of our power, our womanness; we give up the future of our worlds.”[8] In The Forty-Year-Old Version, rap moves Radha’s spirit. Rap moves her toward promise. It is an expression of the core of her self—of her empowerment and womanhood. For Radha, rap is a vital necessity. Rap is not a luxury.

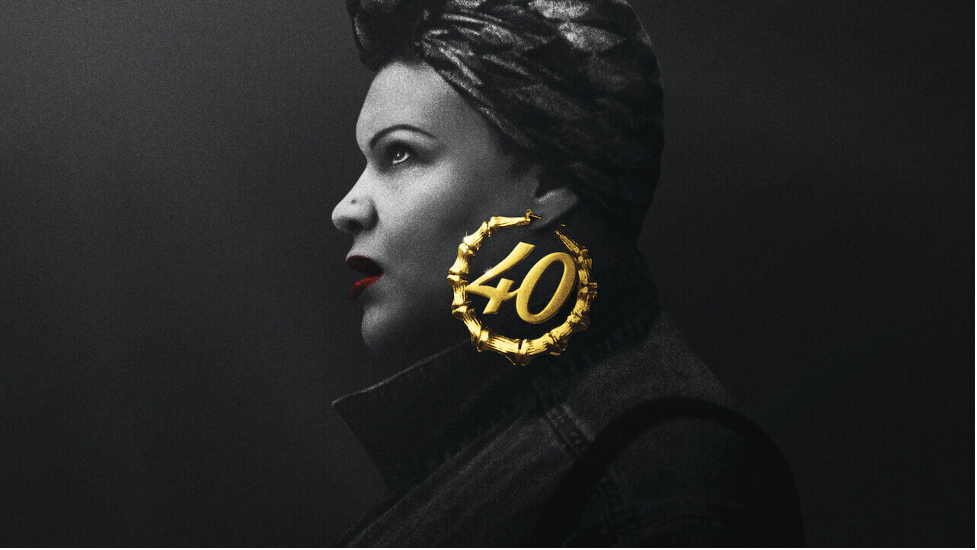

Image Credits:

- The Forty-Year-Old Version (Netflix, 2020).

- Radha (Radha Blank) with J. Whitman (Reed Birney). (author’s screen grab)

- Radha Blank in The Forty-Year-Old Version (IMDB).

- Radha with her agent, Archie (Peter Kim). (author’s screen grab)

- Radha in the recording studio (NY Times).

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (NY: Ten Speed Press, 2007), 37. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- bell hooks, Reel to Real (NY: Routledge, 2009), 129-130. [↩]

- Lorde, Sister Outsider, 39. [↩]

- Ibid, 37. [↩]

- Imani Perry, Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 38. [↩]

- Lorde, Sister Outsider, 39. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

Since college, I’ve dreamed of rap. Thank you, your article opened up another side of this life.