Gay Democratic Socialist Disruption on Television in 1971

Finley Freibert / University of Louisville

Consider the following quote:

Because capitalism in America is proven to be exploitative on a vast and growing scale (the 1% of American families at the top get twice the income of all 20% at the bottom), I advocate making America socialist and redistributing the national wealth equitably. I advocate democratic socialism.[1]

The quote seems contemporary.[2] It sounds like someone talking about current economic inequalities exacerbated by the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and continuing to spiral out of control. It uses “the 1%” in the sense that it was employed by the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011. It identifies and condemns the grotesque consolidation of wealth by the few at the expense of the rest of us. It sounds like something Bernie Sanders would say.

The quote is from a gay democratic socialist speaking nearly fifty years ago. It is representative of a gay democratic socialist branch of gay liberation that expanded across the US from 1969 to the mid-1970s. While the nuances of the definition of democratic socialism depend on the contexts of its use, its associated rhetoric and emphasis on egalitarianism—precisely antithetical to authoritarian socialism—remain strikingly constant.

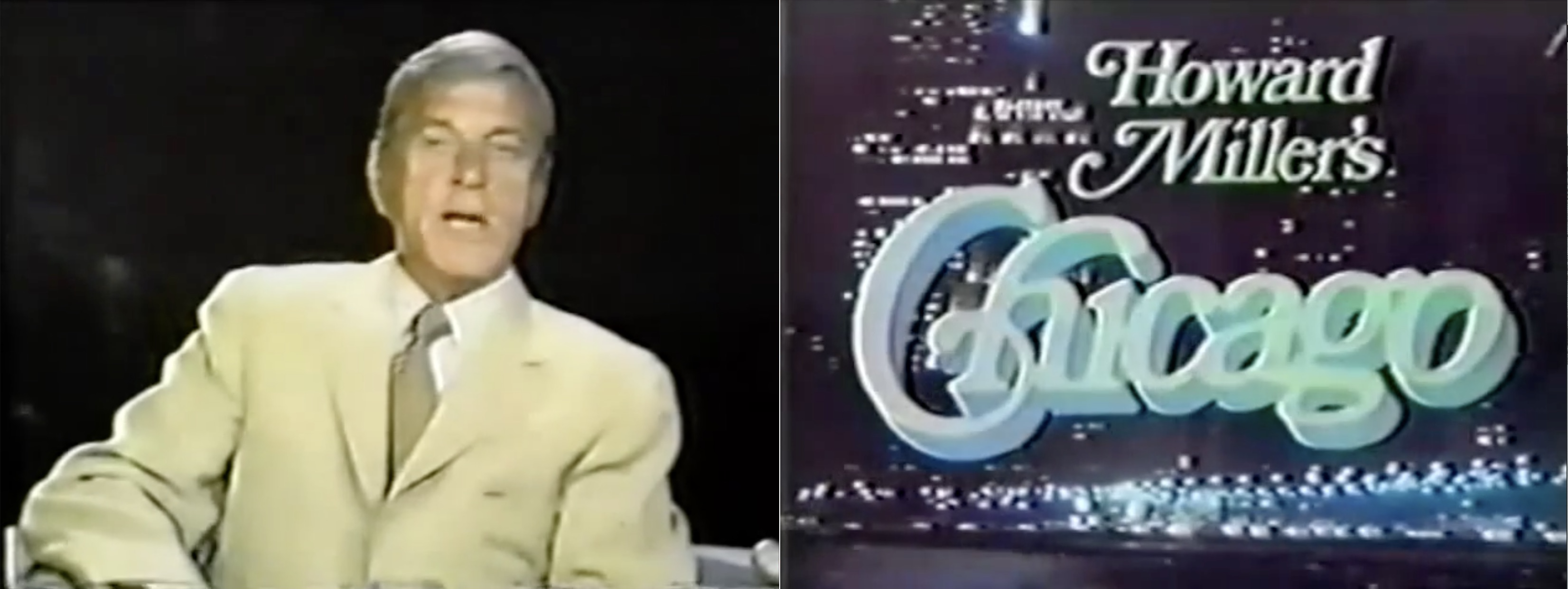

Reverberating the critical sentiment in the quote is the above image, a contemporaneous televised moment of chaos.[3] In the image, an alleged gay democratic socialist (the bespectacled youth with a mop top) confronts Dr. David Reuben, an author (the central foreground figure) who grossly misrepresented gay men for monetary gain. Thinking through this gay democratic socialist disruption of televisual flow provides a historical avenue for approaching recent considerations of what constitutes a gay politics.

Dr. David Reuben’s bestselling non-fiction book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask) was first published in 1969. The book capitalized on the sexual revolution and was intended for the mass market in the vein of popular texts on sexuality from the time.[4] Feminists criticized the book for the author’s sexist discussions of women’s bodies and sexualities; gay men criticized it for outrageous speculations on gay male sexual experiences.[5] The book’s popularity and Reuben’s frequent presence on talk shows to promote the book were indicative of an emergent monetizable form of self-help that Elena Gorfinkel calls “a developing literature of sex-help” wherein “the private sphere of sexuality could be accessed and become an object of consumption.”[6] Gay liberation activists were not solely outraged by his false claims about gay life but above all the profit-oriented capitalization on those claims.

While Reuben was promoting the book during a taping of Howard Miller’s Chicago on February 14, 1971, a group of approximately fifteen gay activists interrupted him to contest his bizarre and bigoted claims about gay men. Gay activist Murray Edelman escalated the confrontation by storming the stage, demanding that Reuben answer. Edelman was intercepted by security, and the show’s host condemned Edelman as a member of the Red Butterfly, “a group of homosexuals with Marxist influence in politics.”[7]

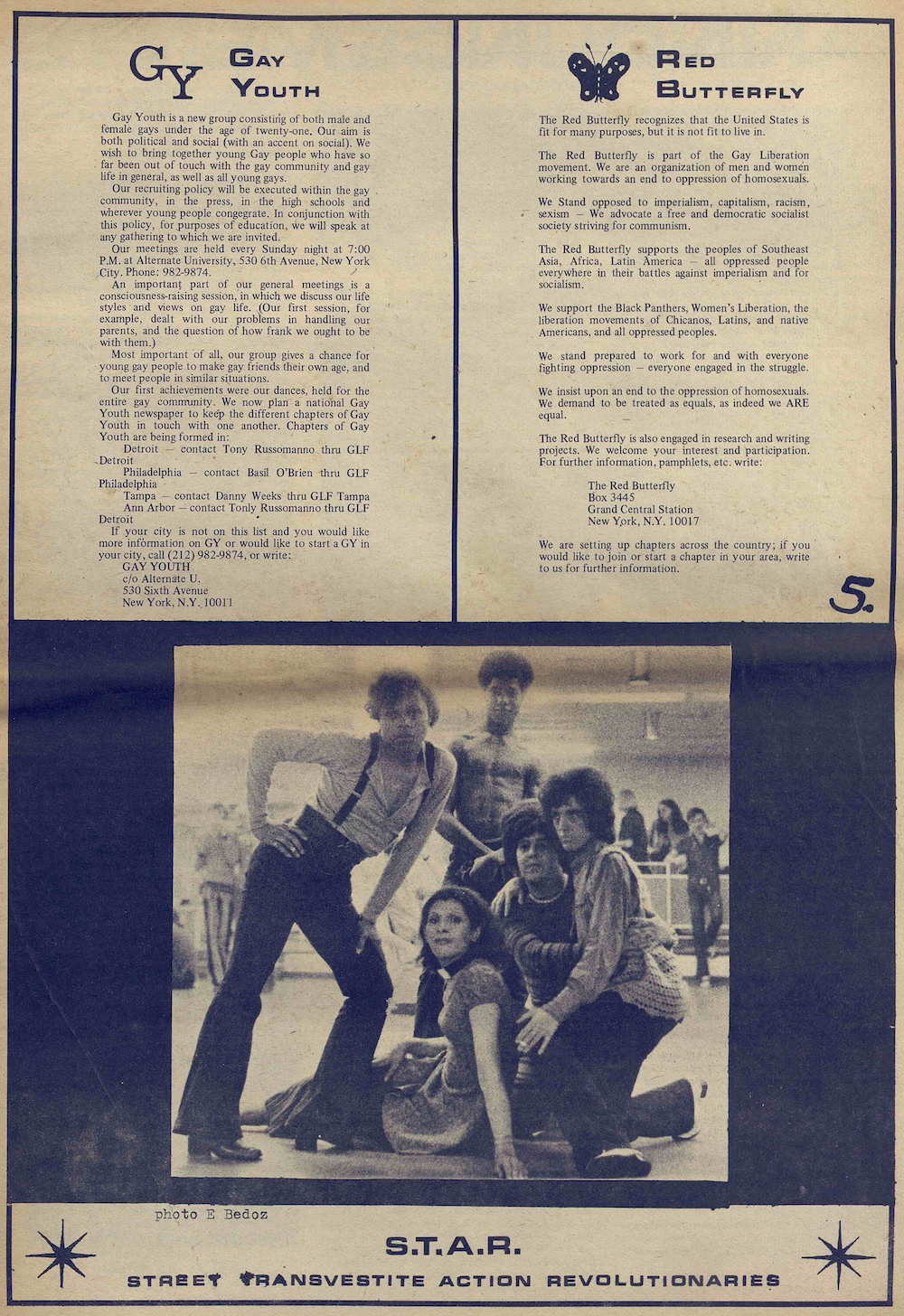

It is unclear if Edelman was actually a Red Butterfly, so it is plausible that Miller’s statement was anti-left red-baiting given Miller’s right wing affiliation.[8] Yet rather than alleging Edelman was simply a gay communist, Miller’s statement displayed a surprising level of specificity and relative accuracy; the Red Butterfly was a gay Marxist group, which also self-identified as democratic socialist.[9] Regardless of whether Edelman was a member of the group, the public identification of the disruption with the Red Butterfly and the action’s political and economic purpose align it with a gay democratic socialist imprint.

This protest on Chicago television was part of a tradition of gay liberationist zaps—confrontational direct action toward a public figure or institution with the aim of generating publicity. Gay zaps and other forms of gay media intervention and advocacy have been well-documented.[10] While there has been acknowledgement of the economic interventions of gay zaps with tactics like boycotting, much of the literature centralizes representational concerns as the primary focus of gay media activism of the 1970s. While clearly part of gay liberationists’ quarrel with Reuben was his fabricated claims about gay men, I’d like to adjust the lens on this moment of gay liberation media activism to consider the possibility of socio-economic critique offered by groups like the Red Butterfly.

Rather than read this protest as exclusively a representational quarrel over what constitutes “authentic” gay cultural and sexual practices, what if we view it as a critique of media industries’ collusion with—and embeddedness in—fundamentally inequitable economic infrastructures? A reading of this action as informed by sexuality and political economy is in line with what Heather Berg writes of different yet intersecting contexts of feminist sex-work activism: “the point is not that there is an antipathy between radical sexual and radical anticapitalist politics—the battles are the same: capital despises both workers and sexual minorities who refuse to assimilate to the nuclear family it requires in order to reproduce labor.”[11]

Congruent with democratic socialist emphases on collectivity and socio-economic critique, Edelman urged that his action should not be recognized because of the publicity that it garnered—i.e., the newspapers that sold it as a front-page story—but rather because it was a call to solidarity as “an action directly out of our felt oppression.”[12] Edelman later reflected on his motivations for spontaneously storming the stage. During the taping as he silently sat in the studio audience, Edelman envisioned Reuben’s books being sold and with the books’ circulation, he imagined the exposure of millions to Reuben’s ideas.[13]

Edelman’s emphasis on solidarity in opposition to mass market product circulation is key to understanding how the zap was an economic intervention. While there is no doubt that public attention to the gay liberation cause was one objective of zaps, gay direct actions—rooted in the tradition of labor organizing and often themselves referred to as “gay strikes”—were nearly always intended to intervene in the flow of capital.[14] Producers of the talk show invited members of the University of Chicago Gay Liberation group to the show’s taping of the interview with David Reuben because homosexuality was considered a “lucrative topic.”[15] However, upon learning of their invitation, Reuben refused to discuss the subject of homosexuality on the show for fear that it would diminish book sales.[16] Following the confrontation, Reuben walked off the program and cancelled a future guest appearance on WLS. In sum, the Edelman-led zap disrupted both the local promotion of Reuben’s book and threw a wrench in the scheduling of two WLS shows. Further reflecting on the zap, Edelman linked the action to a broader gay liberation campaign in Chicago to prevent all advertising and sale of the book in the area.[17]

Why does this matter?

This column was written during the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries, wherein popular candidates included a gay man and a democratic socialist. Through his policies as a mayor the gay candidate enacted class war against the homeless and working classes. He has also red-baited the democratic socialist and enthusiastically displayed contempt for postwar activism. Concurrently, everyday people actively confronting their own conditions of impoverishment, such as graduate students in the University of California system, have been fired from their jobs and threatened with deportation. It is also a time when political affiliation with democratic socialism can lead to disciplinary career actions, such as for David Wright of ABC News, or even one’s personal information being cataloged on a public blacklist intended to incite harassment.

While certainly there have been conservative groups across the gay political spectrum, socialism has been a formative component to gay activist cultures and historiography.[18] Revisiting televised gay democratic socialist outrage underscores how central socio-economic considerations have been to the gay liberation project.[19] Reflecting on where gay politics has been can help us imagine an equitable horizon for its future.

Image Credits:

- Gay disruption on Chicago TV, 1971 (clipping from Mattachine Midwest Newsletter, February 1971, 18.)

- Howard Miller and the logo for Howard Miller’s Chicago, 1971 (author’s screen grabs).

- A fused layout grid presents the Red Butterfly in solidarity with other key liberation groups, Gay Youth and S.T.A.R. (clipping from Come Out, December 1970, 5.)

- Tip Hillan, “Letter to the Editor,” Vector, February 1972, 7. [↩]

- That is, aside from the exponential increase in the wealth gap represented by this quote’s percentages, which reflected the 1970s. [↩]

- The presence of sporadic circular banding, blurred movement, rounded rectangular masking, and slight non-rectilinear perspective typical of a convex screen all suggest the image is not a photograph of the scene, but a still capture of a televisual image and meant to be understood as such. [↩]

- The focus on pathology and sensationalism in Reuben’s chapter on homosexuality is more in line with the phobic and conformist position of popular psychology. For a differentiation between the popular psychological and sociological mass market genres see Jeffrey Escoffier, American Homo: Community and Perversity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 86–93. [↩]

- Representative reviews in the feminist and gay press respectively include “Amazon’s Eye View,” Sappho 1, no. 5 (1972): 11; E.L. Sutton, “Mailbag: Reuben Peddles Baloney,” Advocate, February 3, 1971, 23. [↩]

- Elena Gorfinkel, Lewd Looks: American Sexploitation Cinema in the 1960s (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 170. [↩]

- William B. Kelley, “Gays Protest Reuben ‘Book,’” Mattachine Midwest Newsletter, February 1971, 1. The article went on to state, “Miller’s comment was the first hint that one [Red Butterfly group] might exist in Chicago.” In other words, given that the Red Butterfly was based in New York, even the gay press expressed surprise over the possibility that a new group had formed in Chicago. Indeed, by January 1972 the New York Gay Activists Alliance was listing chapters of Red Butterfly in both Chicago and Delray Beach. [↩]

- For the quintessential historical account of the lavender scare see, David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004). [↩]

- See Image 3 for one of several places where the Red Butterfly self-identified as democratic socialist. “Red Butterfly,” Come Out, December 1970, 5. [↩]

- Some key texts include Vito Russo, The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (New York: Quality Paperback Book Club, 1995), 181–245; Stephen Tropiano, The Prime Time Closet: A History of Gays and Lesbians on TV (New York: Applause Books, 2002); Steven Capsuto, Alternate Channels: The Uncensored Story of Gay and Lesbian Images on Radio and Television (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 2000); Matt Connolly, “Liberating the Screen: Gay and Lesbian Protests of LGBT Cinematic Representation, 1969–1974,” Cinema Journal 57, no. 2 (2018): 66–88. [↩]

- Heather Berg, “Working for Love, Loving for Work: Discourses of Labor in Feminist Sex-Work Activism,” Feminist Studies 40, no. 3 (2014): 711. [↩]

- Murray Edelman, “The ‘Heavy-Set, Bearded Youth’ Responds,” Chicago Gay Alliance Newsletter, February 1971, 11. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- [1] Examples include the gay strike of May 1969 initiated in the Bay Area to protest the police killing of Frank Bartley in Berkeley, and the National Gay Strike Day planned by the Gay Liberation Front at the 1970 meeting of the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations. [↩]

- James Coates, “Miller Talk Show Ends in a Big Flap,” Chicago Tribune, January 15, 1971, 14. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Fred Winston, “Gay Lib Member Confronts Sex Book Author on TV,” The Chicago Maroon, January 22, 1971, 4. [↩]

- Numerous folks have contributed to the progressive historiography of gay politics including John D’Emilio, Lisa Duggan, Jeffrey Escoffier, Jonathan Ned Katz, Gayle Rubin, and Barbara Smith, among numerous others. For a general overview see, Jeffrey Escoffier, “Left-Wing Homosexuality: Emancipation, Sexual Liberation, and Identity Politics,” New Politics, Summer 2008, 38–43. [↩]

- While liberationists diverged from the conservative ethic of sexual identity privacy generally ascribed to the earlier homophile movement, the dual commitment of both groups to socialist critique provides a throughline from the early communist-inspired homophile cells, into the gay Marxism of the Red Butterfly, and through to the intersectional, anti-racist, and internationalist coalitions expansively documented by Emily K. Hobson. Emily K. Hobson, Lavender and Red: Liberation and Solidarity in the Gay and Lesbian Left (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016). For a key analysis of the radical left tendencies of early homophile groups, see Martin Meeker, “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and Male Homophile Practice, 1950s and 1960s,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 10, no. 1 (2001): 78–116. [↩]

Pingback: Convocatorias en publicaciones científicas – FACSO Educación Virtual

However, having a simple conversation about the holiday or picking a low-key gift or event can take the stress out of the day and turn it into something you enjoy.