Getting in Synch with Music Videos

Laurel Westrup / University of California, Los angeles

On September 8, 2019, The Lumineers’ III[1] premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. Directed by Kevin Phillips, the film is comprised of ten music videos—one for each track on the album—and like the album, it tells the dark, multi-generational tale of a family destroyed by addiction. As such, we might call III a visual album, though each of the videos has also been released online in a standalone capacity.[2] One of the lead videos released on YouTube, “Gloria” is especially grim. It introduces us to alcoholic mother Gloria Sparks, who loves her baby but wreaks havoc on her family. The sad, elliptical story in this installment of III culminates in a horrible car crash with uncertain repercussions. “Gloria” features the type of loosely sketched, socially conscious narrative that is on trend in current music videos but is by no means new.[3] A far cry from the glitz and glam of some pop videos, “Gloria” is both moving and serious (as signaled by a plug for Alcoholics Anonymous in the credits below the video). This kind of seriousness (not to mention film festival premieres) sometimes earns music videos a “cinematic” label, but I would argue that “Gloria” is still a music video at heart, and that its music video qualities are as compelling as its narrative.

What are these qualities, though? Defining music video has proven an elusive task. Recent scholars have often dodged the question, settling on something like Steven Shaviro’s “I know it when I see it.”[4] Carol Vernallis suggests that the radical expansion of music videos, now no longer tethered to MTV or televisual limitations, means that we can no longer rely on the definition we once had, which was something like “a product of the record company in which images are put to a recorded pop song in order to sell the song.”[5] This definition certainly feels dated to us now, but its emphasis on commerce was always too limiting. Think of Bruce Conner’s experimental films inspired by Ray Charles and Devo,[6] or Kenneth Anger’s Kustom Kar Kommandos. Can’t we recognize something music video-esque in these non-commercial (or anti-commercial) works? Perhaps we don’t need a definition that delimits music video according to promotional function, medium (film, video, digital), or means of exhibition. Rather than policing the boundaries, can we ask what’s quintessential to this form?

If it’s true that we know a music video when we see it (and, importantly, hear it), how do we recognize it? When I ask students in my music video seminars this question, they usually begin by articulating a relationship between music and moving images, and ultimately clarify that music must drive the images in order for us to call this relationship music video.[7] This doesn’t mean that the images are merely supplemental, though, students point out. Nor does it foreclose the possibility of dialogue, sound effects, silence, or other music.

Giulia Gabrielli suggests that one of the constitutive ways that music and images “get in touch with each other” in music videos is through “synchronization points,” a term she draws from Michel Chion’s extensive work on audiovisual relations.[8] Synch points provide consonance between musical and visual qualities. They can arise when editing, camera movement, or on screen movement matches a rhythm, or when a lyric is visualized, to give just a couple examples. Gabrielli valorizes the kind of tight synchronization we find in Michel Gondry’s video for Daft Punk’s “Around the World,” where each of five character types is tightly choreographed to match one musical “voice” (bass, guitar, drums, synthesizers, or vocoder).

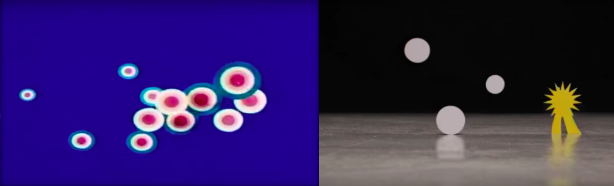

This emphasis on audiovisual synchronization is not new, of course. It features regularly in the long history of artworks loosely labeled visual music. Purists will tell you that visual music is not a sound art—rather, it is visual art that draws upon musical structures, feelings, or languages.[9] But visual music artists as diverse as Oskar Fischinger and John Whitney have paired their visual compositions with music to form compositions that we might recognize as music videos. There is clear continuity between this work and more recent music videos such as Shugo Tokumaru’s “Katachi,” Half•alive’s “still feel,” and Gnarls Barkley’s “Crazy.” These videos, like their visual music predecessors, translate musical qualities into colors, shapes, and movements.

If the tradition of visual music opens various avenues of audio-to-visual translation, though, it also raises questions about how tightly image should be synchronized to music. Fischinger told fellow filmmaker Hans Richter, who was critical of his work, “I never tried to translate sound into visual expressions.”[10] Rather, Fischinger saw the kind of tight synchronization implied by translation as just one of many resources available to visual music artists. Using the metaphor of a river as the music and a person strolling along that river as the images, he suggests that “The film is in some parts perfectly synchronized with the music, but in other parts it runs free … sometimes we even go a little bit away from the river and later come back to it and love it so much more—because we were away from it.”[11] Audiovisual synchronization in music videos often works this way.

Take “Gloria,” for instance. During significant stretches of the video, the image track attends more closely to the story than the music, and we could easily be watching a short film with musical score. But the video also includes many moments where images reinforce musical elements. The video begins with a ticking sound from a watch, which is quickly echoed on the guitar, and this sound is matched not only by several images of a watch, but by a visual ticking as we cut back and forth between the watch and a bottle cap being unscrewed. From there, long zooming takes of Gloria tilting a bottle to drink correspond with four consecutive bass drum kicks, which usher in the first lyrics. These shots introduce the character and her addiction, but just as importantly, they match the agitated quality of the music. Throughout the video, the images stray some from the river of music, but they always return to translate a lyric (“found you on the floor”) or accentuate a musical element (the collision of drumsticks becomes a bottle glancing off of logs). Synchronization points remind us that both music and image are integral to our experience, and it’s this delicate audiovisual dance that makes “Gloria” a music video.

Not all music videos strike this balance, though. Carol Vernallis proposes that in music videos, music and image function like a couple who must constantly negotiate each other’s needs. “We can assume,” she says, “there are issues of dominance and subservience, passivity and aggression.”[12] The same might be said of the artistic and industrial forces at play in the making of music videos. What happens, for instance, when a musician’s vision and a director’s vision are not in synch? Can music and image still “get in touch”? In my next column, I’ll turn to the question of how music videos work.

Image Credits:

- Music video gets serious. Anna Cordell in “Gloria.” (author’s screen grab)

- The Paris Sisters’ rendition of “Dream Lover” drivers Kenneth Anger’s Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965).

- Each set of characters corresponds to a musical voice in Daft Punk’s “Around the World.”

- Visual music then and now: Oskar Fischinger’s “An Optical Poem” (1938) and Shugo Tokumaru’s “Katachi” (2013). (author’s screen grabs)

- “Gloria” opens with a series of audiovisual synch points that accentuate musical features.

- Album: Dualtone Records and Decca Records, 2019. [↩]

- All ten videos are available, along with a trailer for the project, on The Lumineers’ YouTube channel. [↩]

- Aerosmith’s 1989 video for “Janie’s Got a Gun” would be right at home in the #MeToo era, though its rape-revenge narrative might feel regressive. Recent examples that I’ll return to in a later column are Logic’s “1-800-273-8255” and Hayley Kiyoko’s “Girls Like Girls.” [↩]

- Steven Shaviro, Digital Music Videos (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 4. The quotation is a nod to Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous non-definition of pornography. [↩]

- Carol Vernallis, Unruly Media: YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 208. [↩]

- Conner is often referred to as the grandfather of music videos, and J. Hoberman has elsewhere called his music films “art-world music videos.” [↩]

- A big thanks to the students in my music video seminars past, present, and future. They have inspired many of my insights and examples here and elsewhere. Thanks also to Paul N. Reinsch, fellow music video aficionado and generous interlocutor. [↩]

- Giulia Gabrielli, “An Analysis of the Relation between Music and Image: The Contribution of Michel Gondry,” in Rewind, Play, Fast Forward: The Past, Present and Future of the Music Video, ed. Henry Keazor and Thorsten Wübbena (Piscataway, NJ: Transcript, 2010), 96. [↩]

- See, for instance, the work of visual music scholar William Moritz. [↩]

- Quoted in Cindy Keefer, “Optical Expression: Oskar Fischinger, William Moritz and Visual Music: An Edited Guide to the Key Concerns,” in Oskar Fischinger 1900-1967: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction, ed. Cindy Keefer and Jaap Guldemond (Amsterdam: EYE Filmmuseum; Los Angeles: Center for Visual Music, 2012), 165. [↩]

- Quoted in Keefer, “Optical Expression,” 166. Whitney similarly avoided exact translation of music to image. Bill Alves writes, “Although Whitney wrote of musical harmony being ‘matched’ in the visual domain, he resisted automatically mapping one characteristic to another across media, instead referring to this connection as a ‘complementarity.’” Bill Alves, “Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music,” Organised Sound 17, no. 02 (August 2012): 116, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771812000039. [↩]

- Vernallis, Unruly Media, 210. [↩]

That was the best ever film I have watched in recent times, thanks for the listing and detailed review about my favourite flick.