Fire in Her Belly: Gendered Standards of Comedic Discourse

Ashlynn d’Harcourt / The University of Texas at Austin

On May 30, 2017, the celebrity news website TMZ published a photograph of comedian Kathy Griffin holding a mask of President Donald Trump covered in fake blood. The title reads, “Kathy Griffin Beheads President Trump,” followed by the tongue-in-cheek, ”I Support Gore.” TMZ asked the question, does this photo incite violence?

Griffin has her roots in stand-up comedy, which she began performing in the 1990s. She has made a number of guest appearances on television shows, including on Seinfeld and The X-Files. Griffin also starred in NBC’s Suddenly Susan (1996-2000) and her Bravo reality television show, Kathy Griffin: My Life on the D-List (2005-2010), but she has never given up live stand-up and has recorded a number of comedy specials. In addition to laughs, stand-up comedy delivers cultural critiques like other forms of experimental theater and performance art. As early antecedents to the stand-up comic, vaudeville performers were recognized as having “a fire in their belly which makes you sit up and listen whether you want to or not.” [1] Many early sound films, with their fast-paced strings of gags and physical humor, showcased the vaudeville actor’s “performance virtuosity”; for example, the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields. [2] These anarchistic comedies are described by Henry Jenkins (1992) as Hollywood’s attempt to assimilate the vaudeville aesthetic into the film practices of the 1930s, and they tended to emphasize the creativity of their comic stars in lieu of the dominant narrative structures of cinema at the time. Eventually, this style of film comedy was abandoned for the more subdued style and orderly format of the Hollywood romantic comedy, but vaudeville and anarchistic comedy played a valuable role for audiences, much like stand-up does today. By transcending the everyday experience with absurdity, these forms of popular entertainment both amuse and provide audiences with a “vicarious escape from emotional restraint,” creating space to question the status quo and expand social discourse [3] .

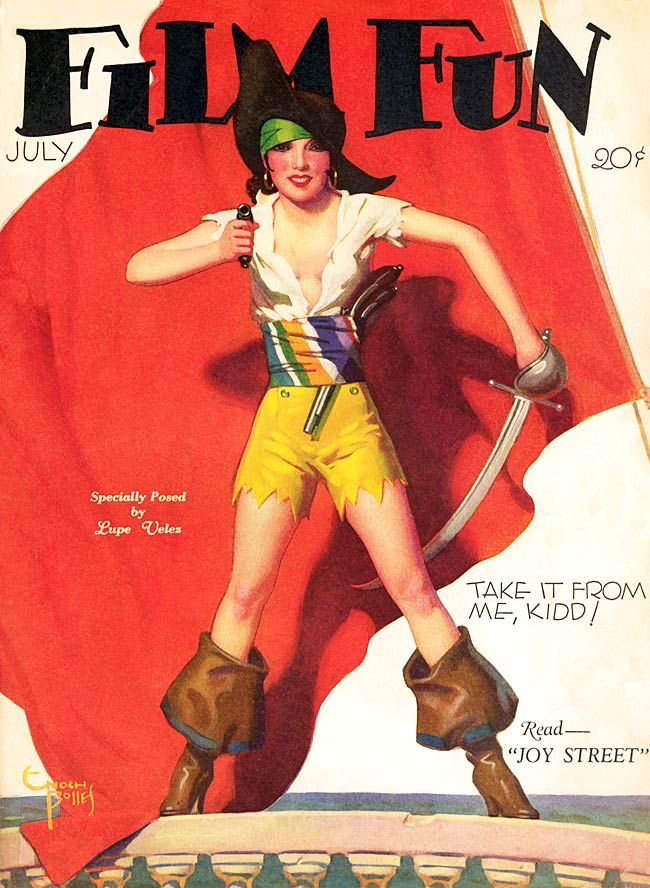

Conceptualizing stand-up as a descendant of anarchistic comedy is useful in understanding the photo created by Griffin and photographer Tyler Shields. There are many similarities between the two types of comedy. In anarchistic comedy, the clown is a social misfit with a marginalized identity, sometimes an immigrant or member of an ethnic minority. [4] Stand-up comics are predominantly heterosexual, white males, but within the Hollywood social stratum, most are D-list celebrities on the fringe of fame. This is particularly true of Griffin, who strongly identifies with her D-list status and uses her position as an outsider to joke about Hollywood A-listers. [5] Anarchistic comedians are excessive, demonstrating “gross and unquenchable appetites”; for example, in Groucho Marx and Winnie Lightner’s gold diggers or Buster Keaton’s drunk in What! No Beer? (1933). [6] Stand-up comics are also excessive in presentation, in their unorthodox language (Richard Pryor) or appearance (Phyllis Diller used her over-the-top style as a punchline as well as to call attention to societal standards of beauty [7]). Finally, both early sound and stand-up comedy contain anarchistic cultural commentaries. Anarchistic comedies are transgressive, offensive even, particularly in their portrayal of class, race, and gender stereotypes. This type of comedy was most successful at critiquing the status quo when the clown was of a marginalized identity rather than vice versa, as in Lupe Vélez playing the stereotype of a Mexican spitfire to expose the biases of a racist white patriarchy.

Griffin posted a video of the photo shoot with the Trump mask to her Twitter feed, which sparked swift condemnation from conservatives and liberals alike. Griffin’s friend and CNN New Year’s Eve Live co-host, Anderson Cooper, tweeted that her participation in the photo shoot was “disgusting and completely inappropriate.” After initially standing by Griffin, Senator and fellow comedian Al Franken caved under pressure from his constituents and disinvited Griffin from a promotional event for his recent book, asserting that her behavior had “crossed the line.”

The photo served as a catalyst for an increasingly familiar phenomenon in the media—the celebrity apology. [8] The mediated script starts with a public gaffe, followed by the media reaction—outrage and criticism—and ends with the celebrity’s apology. After assessing the public’s reaction to the photo, Griffin posted this apology to her Twitter feed: “I sincerely apologize. I’m a comic, I cross the line. I move the line, then I cross it. I went way too far… And I beg for your forgiveness.” She denied any intent to incite violence and explained how the absurdist image was meant as a reference to Trump’s comments about journalist Megyn Kelly during the campaign season, when he stated, “There was blood coming out of her eyes, blood coming out of her… wherever.” The photo is essentially an extension of her stand-up comedy and a critique, not an endorsement, of violence.

Megan Kelly’s questions during the GOP presidential debate.

This time the apology was not enough. The morning after Griffin’s apology, the president tweeted that Griffin “should be ashamed of herself,” referring to the photo as “Sick!” The First Lady disparaged Griffin’s character, and his family repeatedly called for Griffin’s termination by CNN. As a result of this and the extended backlash, Griffin lost her nearly decade-long job as co-host of CNN’s New Year’s Eve Live. The Secret Service tweeted that they were investigating the image after it went viral, prompting discussion on news websites about whether Griffin had broken the law (she had not). The comedian continues to receive death threats from the public for her involvement in the photo shoot.

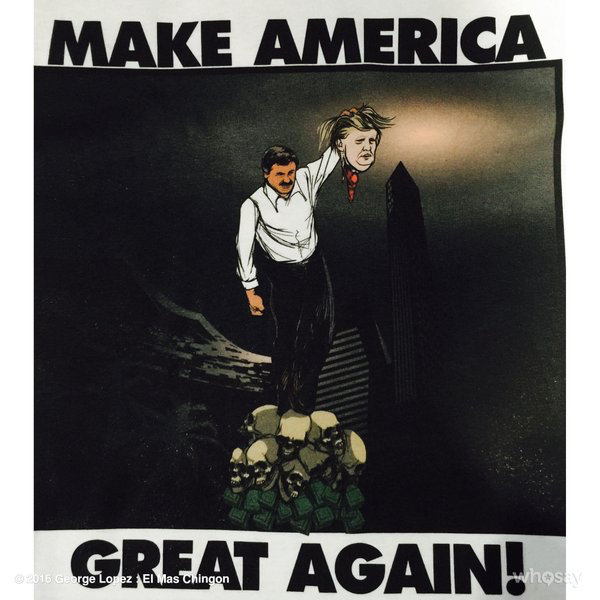

In contrast, comedian George Lopez received a relatively tame reaction during the campaign last year when he tweeted a drawing of a decapitated Trump head held by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. Musicians Marilyn Manson and Snoop Dogg have released music videos over the last year in which the singers, respectively, behead a bloody Trump figure and shoot a gun at the president’s head. More recently, A-list actor Johnny Depp joked about assassinating the president. The backlash to Depp’s comment has been largely partisan; and while the White House Press Secretary admonished his rhetoric, the scolding was directed more toward the media in general than to Depp personally. Back in 2012, shock jock Ted Nugent’s more violent jokes about killing then President Obama launched a Secret Service investigation. None of these male celebrities have been vilified in the media to the same extent as Griffin, nor have they suffered professional consequences for their performances and jokes. Nugent was recently Trump’s guest at the White House.

Why didn’t the cloak of comedy protect Griffin from the magnitude of this recent media backlash? Stand-up is a genre in which female voices—from Joan Rivers to Roseanne Barr, and more recently Margaret Cho and Wanda Sykes—have addressed society’s patriarchal relations of power; [9] [10] [11] however, as with any profession “there is still a firm line of acceptable female behavior” which if crossed is “tantamount to career suicide.” [12] Female clowns have long faced greater restrictions than their male counterparts in what is considered to be acceptable clowning. In early sound films, male actors played a variety of roles, whereas women were only able to escape traditional domestic roles by playing one of a few types such as matrons, wise-cracking sidekicks, or “sexually omnipotent sirens.” [13] If Griffin were a man, or a glamorous siren, would the public’s reaction to the photo shoot have been equally harsh?

Griffin has removed her apology from Twitter and is pledging to continue to mock the president even “more now.” Interestingly, the male photographer and Griffin’s collaborator, Tyler Shields, never apologized and instead defended his freedom of speech in making art. Shields has faced comparatively little public reprisal and, to date, has lost no jobs as a consequence of taking the photo.

Image Credits:

1. Tyler Shields’ photograph of Kathy Griffin holding a Trump mask covered in fake blood, TMZ, May 2017.

2. Mexican actor Lupe Vélez on the cover of Film Fun magazine, July 1929. (author’s screen grab)

3. George Lopez tweeted this drawing of a severed Trump head, February 2016.

Please feel free to comment.

- Lytel, Robert. “Vaudeville Old and Young.” New Republic July 1, 1925, p. 156. in Jenkins, Henry. What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 37. [↩]

- Jenkins, p. 63-72. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 217. [↩]

- Ibid., 224. [↩]

- Mizejewski, Linda. Pretty/Funny: Women Comedians and Body Politics. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2014, pp. 38-40. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 226-227. [↩]

- Gilbert, Joanne. Performing Marginality: Humor, Gender, and Cultural Critique. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004. pp. 117-136. [↩]

- Cerulo, Karen A. and Janet M. Ruane. “Apologies of the Rich and Famous.” Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol 77, Issue 2, May 2014, pp. 123-149. [↩]

- Ibid. 7. [↩]

- Rowe, Kathleen. The Unruly Woman: Gender and the Genre of Laughter. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1995. [↩]

- Mizejewski. [↩]

- Peterson, Anne Helen. Too Fat, Too Slutty, Too Loud: The Rise and Reign of the Unruly Woman. New York: Plume, 2017, Intro. [↩]

- Ibid. 2, 276. [↩]

This is NOT worse than anything Trump has done. Get some perspective.

This is a great event. For the second year our theater wants to get into it. I think that Aladdin’s show https://aladdinshowstickets.com/ should be public. This is the new format of the old fairy tale. You will see many costumes and music

cool article, I really like it