Hallelujah Apocalypse: From Gorillaz to Post-Humanz

Theodore Yurevitch / Florida State University

January 19th, 2017 was the end of many things. The end of a presidency. Almost the end of the Year of the Rooster. Notions of “post-truth” circulated on televised news tickers and Twitter alike. It’s not too hard to imagine one closing her eyes and seeing a vision of fire spurting from geysers; clouds of fallout dust enveloping homesteads; maniacal clowns wielding war hammers; or a man in a hyena mask, bounding over a sun beaten hillock; pigs with orange faces pointing their cloven hoofs, accusing; a processional of white robed figures with black holes punched into their conical heads; Clint Eastwood’s unforgiving squint; an anonymous, pupil-less face with mouth agape; a pyramid with the all-seeing eye flashing technicolor; the liberty bell swinging into a rainbow of starbursts; and a gold gilded elevator, the doors closing on the world, but not before the words ring forth: “Hallelujah money.” You don’t have to imagine this, though. It all happens in the virtual band Gorillaz’s most recent music video: “Hallelujah Money:” a vision of the apocalyptic implications of hyper-mediation and how life might still go on in an increasingly post-human world.

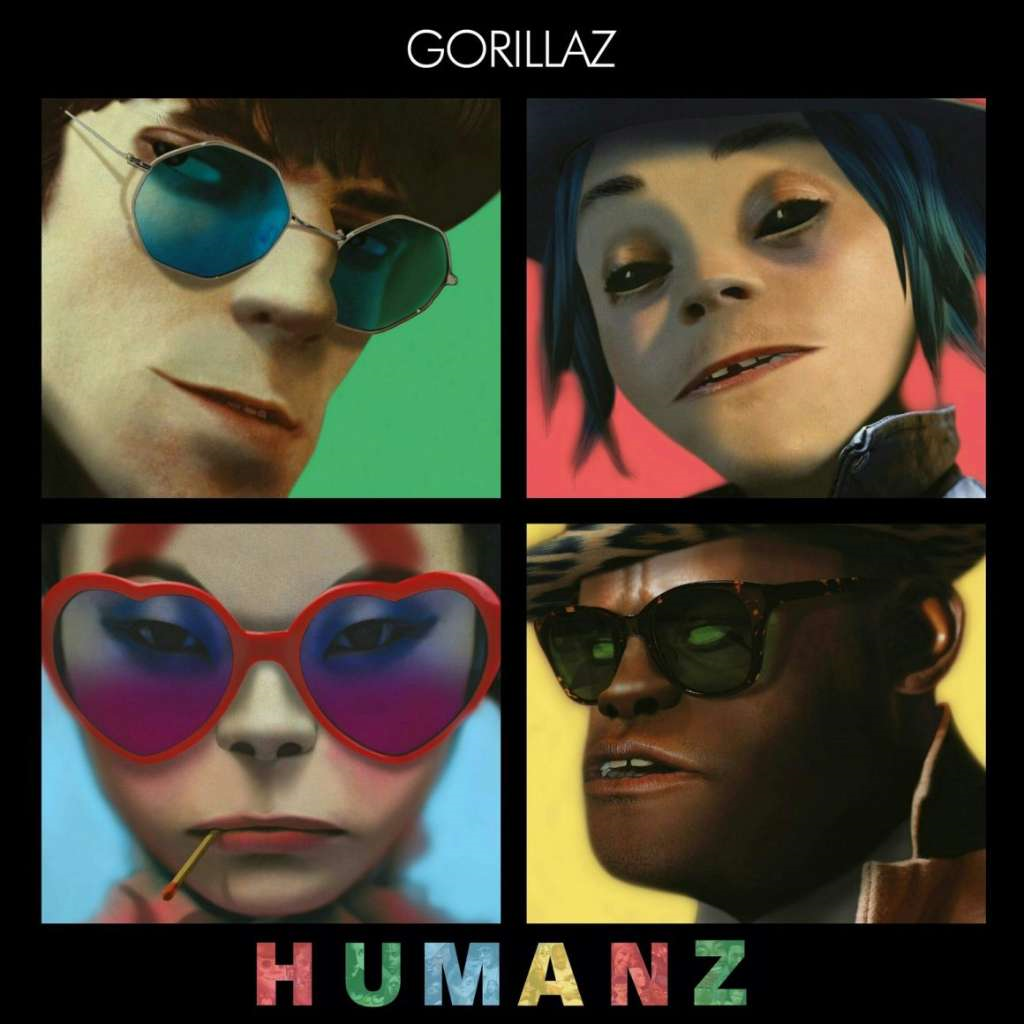

The song and video, “Hallelujah Money,” mark the Gorillaz’s first piece of new music since 2011, but that’s not to say that they haven’t been talked about since then. Following a number of (at times conflicting) announcements, buzz has been steadily building over the last few months for the music/art project in anticipation for a new album, what’s now been slated for release in late April—and aptly titled Humanz. Starting in September, 2016, the experimental band has been releasing digital story books through Twitter narrating the lives of the four “band members” since their last album over half-a-decade prior. Of course, none of these stories are true: since the project’s beginning, the music has always been released under the guise of cartoon characters. A “virtual” band: characters created by Jamie Hewlett complete with fictional backstories. In reality, the music is composed by Damon Albarn and a plethora of collaborators: Snoop Dog, Lou Reed, the Syrian National Orchestra, et cetera. Album to album, the music breaks genre conventions, weaving between electronica, hip hop, folk, minimalist, metal, and more—at times in the same song. Some of their numbers follow the structure of classical western music, others use instruments and artists from the Far East. It’s an eclectic project that has spent the last decade unfolding across various media, telling stories through songs, music videos, animated short films, their own interactive website, spots on television (there was an animated segment on MTV Cribs), and now explicitly through Twitter and, with their new music video’s exclusive release platform, YouTube. Not only are their narratives and themes spread across various media, but the style of the sound itself is predicated by a listener’s ability to access music from across genres and the globe. Here is a group that has made a project out of the “dynamic browsing experience” of spreadable media, packing everything it can into a single brand. [1]

But if, as Marshall McLuhan asserts, “the medium is the message;” what does one make of Gorillaz’s premeditated effort to spread throughout digital spaces and across multi-modal geographies? By building its brand and reputation around deconstructing genre, the group’s work intentionally feels both fragmentary and wholly unified, not unlike what Adorno makes the case for as emblematic of “serious music” where “the detail virtually contains the whole and leads to the exposition of the whole.” [2] While Adorno claims that this dialectical construction in music makes it more complex, his argument doesn’t wholly follow through to see what the value of this complexity might truly be. Gorillaz, on the other hand, makes this dialectical nature not just their conceit, but (in a McLuhanish sense) their whole message. Their work up until this point in time has been invariably concerned with charting a brand of dialectical materialism and entropy (“O Green World,” and “Kids With Guns” are two of many explicit examples), using fictional conceits as a façade for visions of material dereliction, decay and the apocalypse, which have now culminated in their latest work, “Hallelujah Money.”

It is undeniable that the song and video are meant to be read in historical context: they were released on UPROXX’s YouTube channel on the eve of Donald Trump’s inauguration and contain explicit reference to Trump’s highly mediated personage. Not only do the lyrics directly recall to mind things that Trump has publicly said/tweeted with lines like: “And I thought the best way to protect our trees / was by building walls,” but the visual imagery, too, directly alludes to Trump: the gilded elevator that serves as the opening shot and setting of much of the music video is intentionally a replication of the Trump Tower elevator that was so highly mediated in Trump’s transitional period. While much of the lyrics appear initially oblique, the refrain, “Hallelujah money,” makes clear what this song is satirizing. All this is bolstered by the explicitly American imagery of the video’s visuals—the liberty bell, the “eye of providence” found on the dollar bill—as well as sampled clips from such sources as the animated version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm; another clip is meant to resemble the Klu Klux Klan (it’s technically footage from a ceremony of the La Candelaria Brotherhood, but the familiar garb and conflation seems entirely intentional); and there is a repeated scene of notable conservative and Trump supporter, Clint Eastwood (funnily enough, his name is the title of one of Gorillaz’s most popular songs from their first album). The imagery is highly political, but this song is more than just the kind of critique that John Storey provides as one of the definitions of political pop. [3]

The fact that the subject is Trump yields an even more self-referential reading than McLuhan might have supposed. Trump himself, through all his various holdings, television personalities and social media profiles, is as much a product of convergence culture and spreadable media as Gorillaz are. It’s hard to recognize Trump as a human being; rather, he is more aptly read as a Meme in Dawkins’s sense. [4] And while these multiplying layers of self-referentiality (having a metafictional band take on an entirely self-referential, largely content-less personage) might otherwise deride real meaning—circumscribing any sort of take-away for viewers and listeners—the song asks the question necessary to elevate its own commentary in the second refrain: “How will we know / when the morning comes / we are still human?”

There is, of course, the topical element of survival in the age of Trump and policy changes that have many groups rightfully frightened, but there is also the question of how we hold on to our sense of humanity in this ever-increasingly mediated world—one that figures like Trump are so clearly capitalizing on. The Gorillaz project, culminating in their most recent work, suggests that an apocalypse, if not already here, is well on its way; technological determinism through hyper-mediation, the internet, and other digital spheres are the progenitors of something purely constructed, something post-human. These fictions, then, aren’t something subordinated; they have real meaning. What began as a bunch of cartoon characters drawn to vaguely resemble primates are now Humanz, and are as important as the artists behind the fiction; who are still there, and will be for the foreseeable future. It’s up to them, and up to all of us, to determine how we navigate our way through these dialectics, the now no-longer extant line between fact and fiction that mediation has obscured. To the question, “How will we know / we are still human?” perhaps the answer is this: to listen to the song; to realize that you, the listener, exist; and it is your responsibility to listen.

Image Credits:

1. The Gorillaz’s 2017 album, Humanz.

2. Gorillaz’s creator-composers, Jamie Hewlett and Damon Albarn.

3. A gilded elevator serves as the opening shot and setting of much of the music video.

Please feel free to comment.

- Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, Spreadable Media: creating value and meaning in a networked culture (New York, NY: New York U Press, 2013), 5. [↩]

- Theodor Adorno, “On Popular Music,” in Cultural theory and popular culture: A reader (1941): 76. [↩]

- John Storey, Cultural Studies and the Study of Popular Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh U Press, 2014), 109. [↩]

- Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (Oxford: Oxford U Press, 1999), 192. [↩]

I didn’t get the irony until now. Thanks for pointing that out.