Audiences as Subscribers and Netflix’s Notions of Success

Lane Mann / University of Texas at Austin

Exploring how mainstream subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) companies consider and construct their audiences is vital when researching how SVOD platforms – Netflix specifically – brand their popularity. Surveying Netflix’s public discourse reveals a few themes prioritized in the contemporary SVOD industry: engagement, a new understanding of ratings, and brand building techniques.

In Desperately Seeking the Audience, Ien Ang discusses two primary ways the TV industry – as of 1991 – imagines audiences: audience-as-market (connected to commercial service) and audience-as-public (connected to public service). [1] With changing cultures and technologies, legacy TV companies and premium cable channels have imagined audiences in other, distinct ways since Ang’s theorization. An understanding of how SVODs construct audiences both diverges from and overlaps with legacy TV and cable’s new imaginings. Through a focus of SVODs, I have targeted three ways dominant SVOD players imagine audiences: audiences as subscribers, as data, and as promotional partners.

SVOD industry’s interactions with these three imagined audience groups allows for an insight into larger business plans, brand strategies, and notions of ideal viewing practices. Further, these audience categories address culturally shifting ideas of audiences within the ever-changing TV industry. SVOD platforms carefully guard ratings data, thus audiences are constructed differently from network and cable TV audiences, which are inherently shrouded in Nielsen ratings rhetoric. SVOD-produced audience discourse can help divulge how these companies quantify people, imagine user actions, envision their platform, define success, and forecast how their programming is watched. While these are the strengths in examining SVOD audience constructions, it is important to remember that audiences are commodities. As Dallas Smythe theorized, “Audience power is produced, sold, purchased, and consumed, it commands a price and is a commodity.” [2] The imagined audience employed by SVODs and their stakeholders is reductive, utilized for the perception of greater consumer choice and personalization.

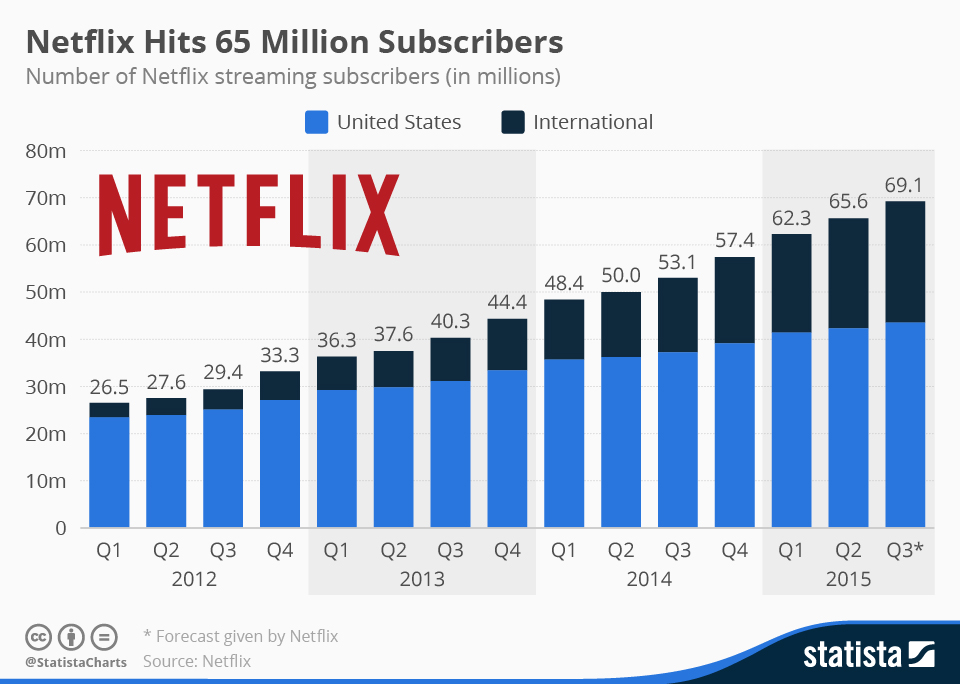

For the sake of this post, I focus on just one of the SVOD imagined audience groups listed above: audiences as subscribers. Also, I use Netflix as a test case and example, since their subscription service is the most publicly known and utilized, with 83 million members in June 2016 – though most major SVODs employ similar rhetoric. Netflix uses subscriber statistics as a proxy for audiences. The company is interested in subscriber data because subscribers drive revenue and appease stakeholders, content creators, and advertisers. While subscriptions statistics do not figure prominently in mainstream press coverage or widespread marketing, the statistics are contained within quarterly reports. These statistics, however, do not give information about audience engagement and viewership (what people actually watch). Put simply, subscriber numbers only detail the amount sold rather than the amount used. [3] Comparatively, insights into Netflix algorithms and their data collection process convey more information about actual consumption patterns and usage, but Netflix relies on subscription figures in reports. Subscriber numbers are invoked, foremost, for intra-industry stakeholders. The idea of “audiences as subscribers” feeds into a larger, industry-held idea that a monthly monetary exchange – your automatic subscription payment – proves success. However, this data does not prove engagement, which is a key asset for modern media brand strategy. And, it doesn’t show how particular viewers regard the platform. Audiences as subscribers is primarily valuable within the industry itself.

Further defining SVOD success through subscribers is challenging. Without access to internal corporate documents or audience engagement data, their performance is difficult to assess. The only available option is raw subscription numbers and, as of 2015, Netflix dominated the market. To survive within the larger TV industry, streaming platforms must cultivate a sense of superiority and active audience engagement to remain competitive and relevant. Subscription numbers only go so far for the platforms, primarily circulating to tout income and challenge rivals.

Netflix in particular, much like legacy TV channels, still relies on imagined audiences to promote and define their perceived success. But Netflix’s conception of ratings is different from legacy TV. As television scholar Jason Mittell writes in The Atlantic, “Netflix simply doesn’t care about ratings – at least not in the way other television providers do.” [4] Netflix still cares about ratings, to be sure, but this is a new conception of ratings. Such a new conception must be considered in future SVOD studies and by TV studies scholars more generally. The “new ratings,” or, the common ways Netflix has defined success without sharing ratings, have been disclosed through award nominations/wins (an appeal to taste cultures), occasional PR releases including viewer and subscriber data (quantifying success), and by marketing high levels of cultural relevance (success measured by engagement). Other TV companies frequently use these metrics too, though as a complement alongside Nielsen ratings.

From examples above, as Netflix shows off to the public in order to demonstrate success, it is clear that the company values people as both a mass of subscribers for monetary purposes and as a mass of engaged viewers, and these two ideas are symbiotic for the company. Building hype by remaining a relevant brand, winning awards, and being included on year-end lists potential creates a beneficial cycle for Netflix: subscribers that become engaged viewers that generate hype and continue subscribing. I agree with Mittell’s claim that, for Netflix, at least externally, “actual popularity is less important than perceived popularity.” [5] Netflix’s marketing strategies strongly construct and promote perceived popularity. Nonetheless, actual popularity is still important when it comes to appeasing shareholders and content producers, because actual popularity translates into income (and loss of churn). Netflix envisions its product as more successful the more people that subscribe, tweet, and share Netflix experiences. This is a different type of popularity than tuning in at 8 p.m. on a Thursday for Nielsen ratings. Netflix’s Chief Content Officer, Ted Sarandos, outlines his criteria for success when he asks, “Is [the show] drawing an audience? … Is it getting positive reception from fans, from you guys, from the critical reception…Is the show positive to Netflix?” [6] There is clearly a balance of numerical popularity, critical acclaim, and brand building happening in the company’s discussion of success – all emerging from Netflix’s imagined audience.

Image Credits:

1. Audiences as Netflix Subscribers

2. Netflix Subscription Data

3. Netflix Brands Success

Please feel free to comment.

- Ien Ang, Desperately Seeking the Audience (New York: Routledge, 1991), 28. [↩]

- Dallas W. Smythe, “On the Audience Commodity and its Work,” in Dependency Road: Communications, Capitalism, Consciousness, and Canada (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1981), 233. [↩]

- Nielsen data is arguably trying to encompass viewership data (amount used/TV viewed). But, just because a TV is on a particular channel does not mean anyone is watching. Though, Nielsen ratings are more relevant to viewership than SVOD subscription numbers. [↩]

- Jason Mittell, “Why Netflix Doesn’t Release Its Ratings,” The Atlantic, February 23, 2016, http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/02/netflix-ratings/462447/. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Alan Sepinwall, “Ted Talk: State of the Netflix Union Discussion with Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos,” Hitfix, January 26, 2016, http://www.hitfix.com/whats-alan-watching/ted-talk-state-of-the-netflix-union-discussion-with-chief-content-officer-ted-sarandos. [↩]

Lane-

So well written and insightful! It’s fascinating to see how Netflix has changed in the last several years and to think about the imagined audience for a service that streams such diverse content. I’d be interested in how Netflix Original programming draws subscribers vs. streaming content from TV or film studios. For example, I read that Netflix will have a deal with Disney this year (including Pixar, Marvel, and Star Wars), which I imagine would be a huge draw. I wonder if Netflix subscriptions are driven more by original content vs. brand recognition, or series that combine both (like Marvel’s Daredevil and Jessica Jones). Will Netflix become more and more a platform for prestige TV and documentaries (much like HBO) with other streaming content as an afterthought? In my mind this has already happened, as the movie selection has vastly diminished in the past 5 years.

Great article!

Fascinating piece, especially to me as a non-consumer of Netflix content in all cases except those that court prestige. That I may fit into 1/3 of the Venn Diagram of “perfect imagined audience” members that SVOD providers look for never occurred to me; it seems more likely given the legacy TV model that skipping one network’d shows with only one or two exceptions (like a SEX AND THE CITY FAN who doesn’t have HBO) fails to succeed as audience engagement. Mann’s argument, helped by Sarandos’s own choice of words, that this is in fact 1/3 of the success model for Netflix is both incisive and startling, while at the same time feeling “so obvious” that I’m disturbed not to have considered it before.

Lane Mann, Thank you very much for sharing your thought. Really, impressive post and informative as well.

Excellent article. I like the way you written this awesome post for us. We are thankful to you Lane.

This is innovative post. Thanks belongs to author for sharing.

Thanks Lane Mann for sharing. So well and excellent written. This is such a good information as well.

This is such a wonderful article.

Pingback: Four Things Your LMS Can Learn From Netflix - Growth Engineering