Trauma Informed Approaches to Media Studies: Reflections From an Epicenter

Scott Tulloch / City University of New York, Borough of Manhattan Community College

It happened suddenly, faculty and students’ phones chimed with a string of tweets from the City University of New York.

All CUNY schools will have a five-day instructional recess March 12-18. There will be no physical classes on campus. Students and faculty will be working on getting ready to have classes delivered via distance-learning for the remainder of the Spring semester. (1/4)

— The City University of New York (@CUNY) March 11, 2020

The largest urban university system in the United States, consisting of twenty-five New York City campuses serving over 500,000 students, shutdown with the stroke of a keyboard.

No one could anticipate how grave the situation would become. Widely circulated images depicted frantic health care workers on the frontlines and makeshift morgues hastily constructed to accommodate the mounting remains. The pandemic brought instantaneous economic devastation, increased food and housing insecurity to New York City. Images and statistics fail to capture the raw lived experience and tragic consequences of the pandemic. The summer came, offering no relief as civil unrest echoed in streets where generations had come of age under the hands of stop-and frisk and broken windows policing. The lives of students and faculty are in upheaval. Faculty and students were and still are teaching and learning in state of trauma.

There is no universal definition of trauma. An often cited clinical definition, from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), labels trauma “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” Widespread experience of trauma among college students has been well documented. A range of studies suggests that somewhere between 67-83 percent of college students have had potentially traumatic experiences. Now, in the context of the pandemic, it is likely that even more students are learning in trauma.

Students at my institution, which primarily services minority, low-income, and first-generation college students, have been disproportionally impacted by the dual pandemics of racism and COVID. The insecurity and fatigue of my students was observable as the spring semester wore on. Students that had attended classes regularly, in good standing before the pandemic, disappeared. Retained students frequently contacted me to disclose heartbreaking experiences of sick or deceased relatives, unemployment in their families, being confined to small apartments, caring for young or elderly relatives, and enduring hours in lines at food pantries.

After multiple waves of COVID, no part of the country has been untouched by the pandemic. Trauma-informed approaches, which assume students have a trauma history that impacts their learning, are critical as the social, economic, and health consequences of the pandemic will linger for years to come. I offer some lessons, from an early epicenter of the pandemic, on how to integrate knowledge about trauma into media studies and general course design.

Scholars have begun to describe a significant connection between media and contemporary conceptions of trauma. According to Amit Pinchevski, psychiatric recognition of the possibility of trauma through the media is gaining traction and recasts understanding of media effects, by shifting “the location of violence from direct to indirect, and the immediate to the mediated [ . . . ] the impact is no longer symbolic but literal, and the damage suffered is not only emotional but clinical.”[1] For example, research has found that exposure to media coverage following traumatic events, such as the Boston Marathon bombing, spreads acute stress among individuals outside the directly affected community. Another study revealed that repeated exposure to mediated representations of traumatic events, such as terrorist attacks or school shootings, resulted in symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Beyond effects at the individual-level, as catastrophic events are consumed and experienced globally through digital media technologies, scholars have started to theorize forms of collective trauma and “trauma culture.” [2] Trauma-informed approaches to media studies highlight the ways media functions as a record and surface for the representation of trauma. Furthermore, media becomes a site of vicarious trauma where individuals and publics can be (re)traumatized. Perennial issues in media studies can be reengaged from a trauma-informed perspective. For example, hegemonic representations of race or gender would be viewed differently from a trauma-informed perspective, particularly when considered in terms of generational trauma.

The extent that instructors engage trauma in media studies courses requires sensitivity. On one hand, media studies courses can provide a space for students to work through trauma. Prolonged and virtual reality exposure therapy have become common forms of treatment for PTSD, suggesting media can also be a tool for survivors to learn to gradually cope with and reduce trauma-related memories and feelings. Attention to trauma in media studies may provide an opportunity for students to acknowledge, normalize, and discuss feelings and responses to trauma. On the other hand, individuals’ cultures affect perceptions of and responses to trauma. Some students don’t want to talk about trauma. Instructors should acknowledge other students might be overwhelmed by discussions about trauma. Instructors may provide content warnings to allow students to opt out and avoid potential (re)traumatization. In some instances it might be best to offer students an escape to more comfortable spaces of the contemporary media landscape, their favorite YouTube rabbit holes or a new Netflix series they’ve been binge-watching. Direct engagement or the avoidance of trauma in media studies courses must be driven by a conscious effort to promote resilience and prevent further harm.

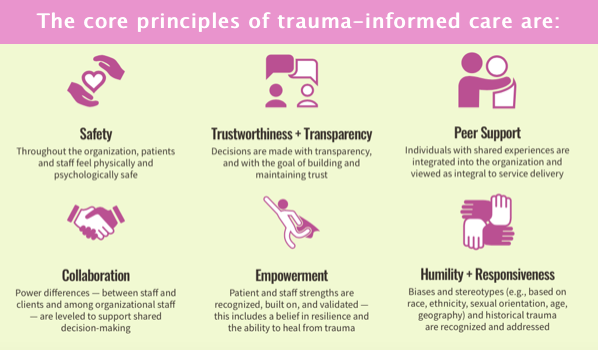

Here are some basic strategies to incorporate trauma-informed practices into general course design, based on guiding principles from SAMSHA and the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Traumatic events bring about a whirlwind of emotions. Students in trauma often feel unsafe, anxious, and fearful. A trauma-informed approach recognizes this emotional uncertainty and works to cultivate a sense of safety, trust, and transparency by providing structure and stability for students. Create class routines and rituals. Post announcements, assignments, and grades on a reliable, reoccurring schedule. Structure class meetings in a predictable pattern. I start each Zoom class meeting with an open share, student updates of good news or otherwise, before moving into course concepts and materials. Design and user interface decisions on learning platforms, such as Blackboard or Canvas, can also help create a consistent and repeatable structure providing further stability for students. Minimize uncertainty by creating a structure that helps students get into the rhythm of learning.

Students in trauma often feel out of control, powerless, and lack a sense of agency. A trauma-informed approach seeks to empower students to have a voice and choice in their own learning. Taking a cue from Universal Design for Learning (UDL), I provide multiple avenues for student engagement, represent course content in a variety of forms, and provide a range of possibilities for studies to express their learning. Let students decide whether they want to read a chapter or short article, watch a video, explore websites, or listen to a podcast. Students often have a preference and will select representations of course content most useful for their learning style and context. Students can also represent their learning in a variety of ways. I’ve traditionally assigned term papers in media studies courses, but during the pandemic I’ve given students more options. Some students submitted final projects in the form a paper, while others created presentations, delivered and posted on YouTube. Other students produced and recorded audio presentations in the form of a podcast. During the pandemic syllabi should be drafted in pencil, flexible and ready to be revised. Students can be brought into the process of course design by inviting them to collaborate on revisions of policies and assignments. My students, in semesters since the start of the pandemic, have frequently created and voted on amendments to the syllabus. Flexibility by design empowers students to become active agents in their learning, while creating a space for collaboration and mutuality.

Students in trauma often feel isolated. A trauma-informed approach aims to produce a sense of support and connection. Remind students you are there for them. Check in with students that have gone missing in action. Sometimes a quick hello and simply asking students how they are doing via email, with no comments about missing assignments or pending grades, is enough to get them back on track. Follow up with these students if they continue to struggle and, when appropriate, refer them to campus resources. For many students, simply the perception of support, availability, and confidence that you are there for them, is reassuring enough. Finally, when you can, be optimistic and positive. Positive emotions can be in short supply during traumatic situations. Remind your students they are resilient, will overcome and succeed.

Awareness of trauma makes better learning environments by urging educators to approach students with radical empathy and care. A trauma-informed approach requires change beyond the classroom, at all levels of an institution, and this systemic change is even more challenging to achieve. The real work of creating a more compassionate version of higher education is just beginning.

Image Credits:

- A man walks by a mural on Houston Street in New York City

- “There will be no physical classes on campus” @CUNY from March 11, 2020 tweet

- Dr. Joseph Ham contrasts the learning brain and the survival brain in trauma

- Tea for Teaching, episode 131, a discussion on trauma-informed pedagogy with Karen Costa

- Core principles of a trauma-informed approach

Let students decide whether they want to read a chapter or short article, watch a video, explore websites, or listen to a podcast. Students often have a preference and will select representations of course content most useful for their learning style and context.