Re-Watching Omar: Moesha, Black Gayness and Shifting Media Reception

Alfred L. Martin, Jr. / University of Iowa

When Netflix announced that it had acquired the streaming rights to a number of Black-cast sitcoms as part of its Black Lives Matter initiative, including Girlfriends (UPN, 2000-2006; The CW, 2006-2008), Sister, Sister (ABC, 1994-1996; The WB, 1996-1999) and Moesha (UPN, 1996-2001), many Black viewers heralded the streaming giant’s engagement with series deemed “classic” among particular segments of Black viewing publics. With 172 episodes (Girlfriends),119 episodes (Sister, Sister), and127 episodes (Moesha), these series had reached the “magic” 100 episodes for syndication, and while Sister, Sister and Moesha were, for a time, syndicated on teen-focused cable channels like ABC Family and Noggin, “old” Black-cast series often have capital only with Black-focused cable channels like BET, Centric, and Bounce TV. Thus, while the acquisition of syndicated fare is cheaper than producing original content for Netflix, for many, introducing a slate of Black-cast programming seemed to gesture toward Netflix’s acknowledgment that Black folks are among its subscriber base.

But revisiting something that largely lived safely tucked in one’s memory can present issues with respect to media reception. In this column, I want to briefly engage Moesha and, in particular, its season two “Labels” episode that is concerned with gossip about a guest starring character’s sexuality (Omar) because it, at the very least, illuminates the importance of social and cultural context with respect to media reception. I use a selection of tweets that were collected using the keyword search “Moesha Omar.” In what follows, I am not suggesting that the ways these Twitter users are reading Moesha and Omar are incorrect, rather, I hope to illuminate the importance of socio-cultural context to the contours of media reception.

Moesha’s “Labels” episode was written by Demetrius Bady, a Black gay writer who had pitched the episode in Season 1 of the series. Once the series became a hit and was greenlit for a second season, although Bady was not yet a staff writer on the series, his story was selected as one of the episodes to go into production. The episode originally aired on October 1, 1996.

While the 1990s has been heralded as the “Gay 90s” because of the number of lesbian and gay characters across the televisual landscape, much of the sitcom representation was episodic. Carter Heywood, Spin City’s (ABC, 1996-2002) Black gay head of Minority Affairs, had just premiered earlier that season on September 17, 1996. Although Ellen DeGeneres was riding high on her eponymous sitcom (ABC, 1994-1998), the character and the actress would not come out as lesbian until the April 30, 1997 “Puppy Episode.” Lastly, Will & Grace (NBC, 1998-2006; 2017-2020) did not premiere until September 21, 1998.

With respect to Black gay characters within Black-cast (or primarily Black-cast) television, there had been only four such characters within Black-cast television history before Omar: Travis, a Black gay civil rights attorney on an episode of Sanford Arms (NBC, 1977), Russell, a Black gay magazine writer and uncle to the series’ titular character, appeared in four episodes of Roc (Fox, 1991-1994), and Antoine Merriweather and Blaine Edwards as Black gay cultural critics in the “Men On…” sketches on In Living Color (Fox, 1990-1994). As I argue in my forthcoming book, Black gay characters were largely absent from the “Gay 90s” because of an industrial imagination of Black audiences as anti-gay.[1] As such, examining the reception of Omar, Moesha and the “Labels” episode is fascinating because “Labels” and Omar were anomalous within Black television discourse.

Three broad themes emerge around the reception of Moesha’s “Labels” episode. The first thread suggests that viewers re-watching Moesha do not root for the series’ axial character in the episode and the series writ large. User @brandonkarsonj tweeted that “Watching “Moesha” as an adult…and I honestly wanna fight her character, strictly for Omar in Season 2, when she outted him. Then, made him feel bad for not coming out sooner.” On the one hand, @brandonkarsonj acknowledges the very personal nature of coming out as gay. Television, whether white- or Black-cast programming, has a propensity to suggest that if a heterosexual character suspects a character’s gayness, that they must not only know, but be ready to disclose that information (as if they have a right to know). Thus, Moesha binds Omar’s sexuality to the knowledge production the series demands under the guise that because he is age-appropriate, he is also a suitable and available love interest for Moesha. On the other hand, the reception of Moesha as unlikable not only (obviously) runs counter to the series’ aims and goals, but it runs counter to the intention of the series’ producers and “Labels’” writer, Demetrius Bady. As Bady told me, in the original version of his script while on a date with Omar, Moesha attempts to kiss him. When Omar refuses her kiss, she tells her friends Kim and Niecy that Omar is gay. Bady’s original script makes Moesha a rumor-starter because of her hurt feelings. Instead, producers Ralph Farquhar and Ron Neal introduce Tracey, Omar’s flamboyantly gay friend to provide a reason for Moesha to think Omar might be gay.

Second, Omar’s story contemporarily (and perhaps in its moment) felt disconnected from the series. As @TonioSpeaks says, “They brought this character out of nowhere, he’s gay, and they throw him back into some abyss. Moral of the story, Moesha is homophobic.” It is unclear if @TonioSpeaks believes the character or the series is homophobic, but two things are clear. First, this user points to the ways Moesha and the Black-cast sitcom use a generic closet to shape the ways Black gay narratives can develop. Using a narrative three-act structure that 1) detects, 2) discovers/declares, and finally 3) discards Black gayness, the Black-cast sitcom throws Black gay characters “back into some abyss.” For contemporary audiences, as understood through Twitter, Omar’s story was unfinished business. Gesturing toward perhaps a lack of knowledge of the ways that “Labels” was, in essence, a “very special episode,” user @LeviSwallowsATL writes, “That entire episode was complete trash, I was sitting there waiting on part 2 so they can clean it up. To think that was the show’s way of addressing the gay issue in the black community. They wasn’t ready to have a real conversation about it and should have left it alone.” In the same vein, user @JaelynGuyton says that “The episode had a lot of potential, but it just kept missing the mark not to mention it’s [sic] poor depiction of gay men. What’s worse is the ending where Omar’s arc is never completed.” While, @JaelynGuyton acknowledges that he watched Moesha (but does not remember the “Labels” episode), he remains convinced that Omar’s story is incomplete. However, Omar’s story is incomplete mostly because it was a conduit to repair Moesha and Hakeem’s friendship.

The last thread I want to discuss in this short piece is reception’s collision with production practices. Audiences have become savvier in the attention they pay to who works behind the scenes of a film or television production than perhaps they were in the 1990s. So, one of the important threads around re-watching Moesha’s “Labels” episode is about its production, and specifically who is working within the show’s production. User @TalkViciousToMe hypothesizes that Moesha’s production staff was comprised of “mostly cishet men in the writers’ room, and a couple women that no one listened to. Can’t blame the actor though because it was a different time, he was young and most of us were conditioned to view queerness as wrong.” On the one hand, @TalkViciousToMe rightly shifts the “blame” from in front of the camera to behind it. On the other hand, Moesha’s writers’ room was not mostly cisgender heterosexual men, but was co-created by Sara Finney, Vida Spears and Ralph Farquhar, and, had Demetrius Bady, a Black gay writer, among its staff. And as Bady explained on @TalkViciousToMe’s thread, “I wrote the [“Labels”] episode and I’m a gay black man. Please understand that we had a production company and a network to answer to. Yes, it was problematic on many levels, but it was also the first time a black gay male teenager was ever represented on television.” To which @TalkViciousToMe responds, “Thank you for trying to give visibility to young Black queer characters, it was necessary to get us where we are today.” Ultimately, Bady’s response helps to provide context that helped this Twitter user understand “Labels” as a piece rooted in the mid-1990s, and therefore, incapable of being all that a 2020 audience might want it to be. In the final analysis, for many of these Twitter users, re-watching Omar was a painful experience. Their experiences differed from the letters Bady received from Black gay men in the mid-1990s, who felt seen for the first time in “Labels.” The ways these Twitter uses read Moesha is not right or wrong. However, what they are doing is attempting to make sense of a 1996 television episode through a 2020 lens. And for many, they came away from re-watching Omar and Moesha, hating Moesha.

Image Credits:

- Black Stories on Netflix (author’s screen grab)

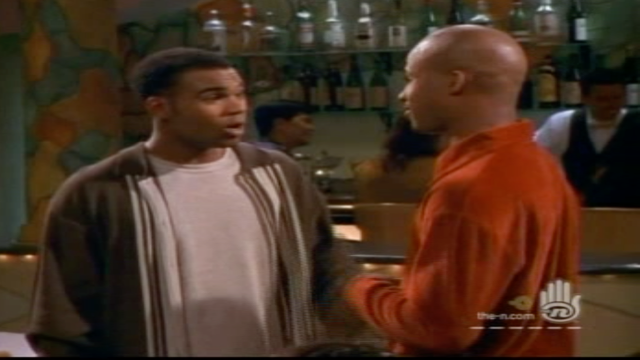

- TV Comedies on Netflix (author’s screen grab)

- Omar in “Labels” episode (author’s screen grab)

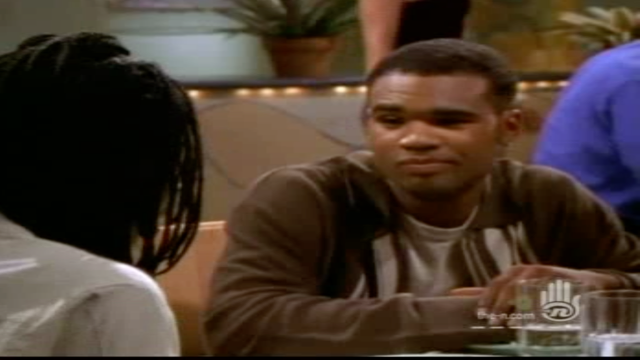

- Omar and Moesha in “Labels” (author’s screen grab)

- For a fuller history of Black gay characters and discourses about Black audiences, see my book The Generic Closet: Black Gayness and the Black-Cast Sitcom (Indiana University Press, 2021). [↩]