Getting Misty-Eyed: Misty Copeland And The Representational Politics Of Black Fandoms

Alfred L. Martin, Jr. / University Of Iowa

Without question, Black ballet dancers infrequently occupy the upper echelons of American ballet companies. My own experience as a ballet dancer often found me as the only Black person (and frequently the only person of color) in a room filled with white swans and their equally white cavaliers. As such, when Copeland was promoted at American Ballet Theatre (ABT) becoming the 75-year-old company’s first Black female principal dancer on June 30, 2015, it was undoubtedly a big deal within the politics of representation—and something I felt compelled to research. Using three interviews with Black female Misty Copeland fans, my aim here is to illuminate the ways Copeland’s Blackness (and rank within the company) has worked to bring African American non-ballet fans into the white world of ballet. In particular, I briefly highlight the ways these Black fandoms rely on a politics of visibility driven by an engagement with paratexts and affect.

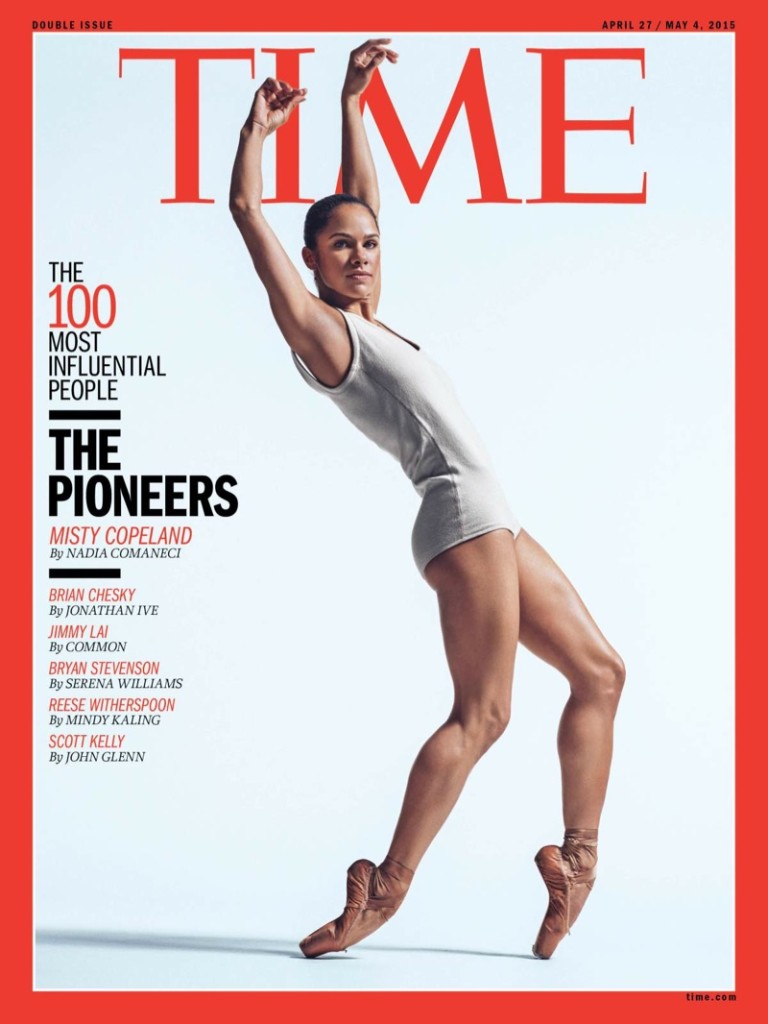

For the Black women I interviewed, the entry point for Copeland is her paratexts. As Jonathan Gray suggests “rather than simply serv[ing] as extensions of a text” paratexts help to shape “our first and formative encounters with the text” (3). Some Black fans, like Courtenay, first saw Copeland on a magazine cover. She says, “It wasn’t even that I read the article, but I saw her pose in the magazine and it drew my attention.” Courtenay illuminates the ways Misty Copeland’s celebrity has extended beyond the relatively elitist walls of the ballet world. Capturing the attention of some Black fans as a dancer for Prince while “moonlighting” from ABT, these fans used their affective response to her to begin driving popular discourse about her “only” being a soloist at ABT. Those who saw Copeland dance for Prince and in any other number of venues including The Arsenio Hall Show(Syndication, 2013-2014) wondered why Copeland was “only” a soloist based upon their affect that what they were seeing was good, rather than their understanding of classical ballet.

Copeland’s position within ABT was inextricably linked to the possibilities of Blackness within the typically lily-white world of ballet. As Keisha illuminates, she, like Courtenay, found Copeland through news stories, only having had a previous dance familiarity with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. Keisha told me:

I heard about Misty and how magnificent she was as a ballerina and she was a woman of color and that’s something you don’t hear about every day. And any time that you hear about anyone of color rising to the pinnacle of their craft, a lot of people put their eye on it. And I was one of those people… She was absolutely phenomenal. And… just to see the amount of Black people that were there, because when I’ve been to other ballets, really, you never really saw a lot of Black people.

For Keisha, the politics of Copeland’s brown body is important, as it was seemingly for the number of Black people within the audience at the Washington, D.C. performance of “Whipped Cream” at which I met Keisha. In other words, it is the very presence of Copeland in a white ballet world that, regardless of her talent, instills a sense of pride among the Black people I interviewed.

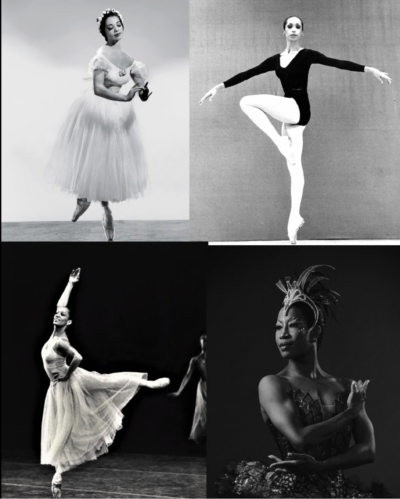

Jordan, although she is a dancer herself, discovered Copeland not through ballet but via the Today show. Jordan says, “On Today they were discussing [Copeland] as a ballerina who was breaking barriers and that was important to me.” The notion of “breaking barriers” is a chief part of Copeland’s star text because it gestures toward the centrality of Copeland’s position within ABT. As Stephanie argues, “I think you’re talking about her basically pushing her way into a white space.” Keisha adds that “I think [Copeland] sets herself apart from the Dance Theater of Harlem and the Alvin Ailey dancers because of the fact that… if she were to be in the Dance Theater of Harlem, she would be just another number… but she would definitely stand out among the rest. But the level of talent that she has… That’s why she’s in American Ballet Theatre. I’m thinking that she just would be another number if she was in another predominantly Black dance company.” In other words, Copeland would still be undoubtedly talented, but her Blackness within a white ballet company carries a greater sense of pride for the Black women I interviewed. At the same time, the discourse of “breaking barriers” discursively untethers Copeland from a history of Black women in ballet, including, but certainly not limited to Lauren Anderson, Debra Austin, Virginia Johnson and Raven Wilkinson.

Much like the discourse about Obama’s election as the first African American president of the United States, Copeland’s brown body within ABT is understood as being aspirational for children, whether they want to be ballet dancers or not. Stephanie says, “I like her because I have two little girls… I’m always happy to see Black representation in fields that we have not historically been in, because I think it’s important for little Black girls to not feel like there are things that they can’t do.” Courtenay adds, “The fact that she is in a genre of dance that has typically been considered only for a certain type of person. A certain type of body structure, a certain type of look. So that has gained my respect because you’re representing young girls who have a dream and they may not look like that but they’re trying to do it anyway. And so that makes me just like aww, come on girl, open the door for people.” In this way, Courtenay demonstrates the ways that Black fans’ investment in Copeland is not just about Copeland, but is also about encouraging the future generations of Black children to reach for seemingly unattainable goals.

In the same vein, Jordan extends Copeland’s import to Black women as well. She forwards, “Misty Copeland is a young woman who basically defied the odds and is a really good example for a young Black woman, like myself, who are pursuing dance… when I was growing up, I didn’t really see a lot of Black dancers in my dance classes. Maybe two dancers… So, seeing that story about her and how she basically kind of went through the same thing I did… And her getting a chance to become a principal ballerina… it inspired me to continue to press through and take dance classes even though I might not be represented in those types of styles of dancing, but to really go for it.” Copeland is not an empty signifier who allows others to map their desires onto her. Rather, through a series of inspirational soundbites, Copeland encourages such a mapping. But in such inspirational messaging, Copeland veers dangerously toward bootstrapping ideologies given that her success is not just about her hard work, but about her luck. In the act of “inspiring” others, she concomitantly forwards the dangerous discourse that “teaches” that if one does not succeed, one simply did not try hard enough. In short, Copeland becomes, whether by accident or by design, the perfect “test case” for an allegedly post-racial era. The failure of the hundreds, if not thousands, of Black ballet dancers who did not “make it” (and certainly not within major international ballet companies) failed because they did not try hard enough, not because there are, and have been, systemic barriers to their entry into such companies.

Copeland’s celebrity is also pedagogical. Even as the documentary A Ballerina’s Tale (Nelson George, 2015) served as a paratext to Copeland, for Keisha, it also served as a “trailer” that made her want to see Copeland perform. She says, “I saw the documentary on Netflix and that was definitely great, and that allowed me to learn more about Misty and appreciate her craft–appreciate her work and the amount of dedication that she put into her career. I just had to see it for myself. I was there, and it was definitely a way of seeing it for myself, but also as to support her.” Similarly, Jordan saw A Ballerina’s Tale which she “came across that by accident. I wasn’t watching it because it was hers. That was probably when I first kind of became familiar with her. I was like, oh yeah, this is the girl I saw on that news story, so I went ahead and watched it.” Shortly after that, Jordan had the opportunity to perform as an extra in ABT’s Detroit engagement of Sleeping Beauty, in which Copeland performed Aurora, the lead role. Jordan recalls that during that time, she has an opportunity to meet Copeland. In that meeting Jordan says she “wanted her to know how important it was for me to just meet her” and that Copeland inspired Jordan to keep dancing.

The confluence of Copeland being in a space that has not historically welcomed Black dancers (although Latinx and Asian-descended dancers have frequently been within ABT’s ranks) and Black fans’ general lack of knowledge around ballet technique shapes Copeland’s Black fandom. Thus, like many fandoms, Copeland’s Black fandom is largely affective. Her Black fans are left Misty-eyed when discussing Copeland because of what she means within the politics of Black representation.

Works Cited:

Gray, Jonathan. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York: NYU Press, 2010.

Image Credits:

- Copeland on Cover of Time magazine as one of “The 100 Most Influential People.”

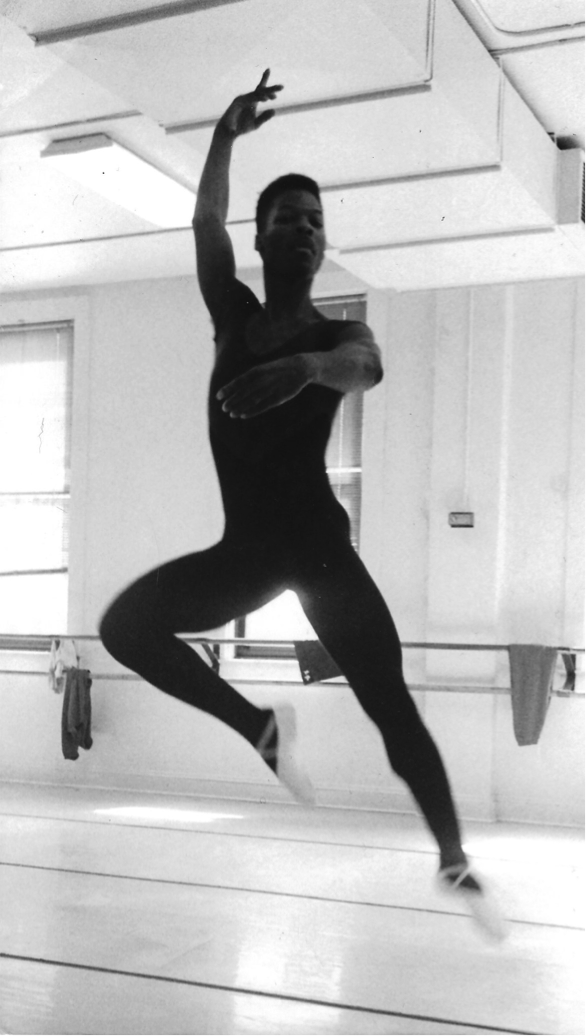

- Me in ballet class at the Joffrey Ballet circa Summer 1994. (author’s personal collection)

- Collage of Black ballerinas (from top left, clockwise): Raven Wilkinson (Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo), Virginia Johnson (Dance Theatre of Harlem), Lauren Young (Houston Ballet), and Debra Austin (Pennsylvania Ballet). (author’s screen grab)

- Misty Copeland circa 2014.