Targeting the Fan: Changing Demographics to Catch Engagement

Jessica Bay / York & Ryerson Universities

The fan is defined by consumption. Fans actively consume and re-consume their favoured text or object. They consume and (re)produce fan objects or practices. Fans also actively consume products related to their fandoms, both in the form of physical objects like figurines and in terms of marketing content that promotes and extends the texts themselves. It is that final consumerist aspect of fandom that I want to approach here. I suggest that marketing agencies are interested in a new idea of the traditional demographic in that they are looking for a “fan demographic” rather than one based solely on age, race, or class. This new demographic includes the type of person who brings a certain level of engagement to their role as audience member and that interest in voracious consumption – of content and object. As an ideal consumer, the fan is indicating not just a model for online engagement, but a model of consumption itself for a broader audience.

Theorists looking at the internet – and its early public history in particular – have discussed the free labor users have put into the medium. Tiziana Terranova, for example, suggests that this work building websites, freely given and enjoyed, was required for the internet to become the place it is today. [1] Abigail de Kosnik takes this idea and extends it to free fan labour suggesting that the material created by fans (websites, fic, art, vids, gifs, meta, etc.) is representative of unpaid labour. [2] Beyond this work that is freely created by fans for fans, we must consider the work fans do directly for the producers. The nature of social media and Web 2.0 is such that fan material is both shared with a wider audience and appropriated by producers themselves. Producers regularly solicit content to be used as advertising material. They have also begun creating avenues for fans to play with that material – in a way that allows them the opportunity to restrict how that material is considered.

This is one very obvious way that engaged fans are “employed” by producers – as creators of content that can then be used to sell the product to the wider market. Another fairly common way that fans, at all levels of engagement, work for producers is through sharing content. This is easy and happens regularly when a new movie trailer is released, for example. The problem from the perspective of the producer, is how to keep content and the name of the brand and/or movie in the public eye between such obvious moments of fan engagement. Who engages fairly continuously with content related to a favoured product? Engaged fans.

This is where a campaign that continuously engages fans directly is useful. As an example of this type of long term campaign aimed at fans, we can look at Lionsgate and their promotion of The Hunger Games series of films (2012-2015). This mini-major has innovated by choosing content with a large existing fanbase. The Hunger Games, for example, was considered a blockbuster book series before the conversations about adapting it for film began. While it can be useful to have a large pre-existing fandom, it is useless – in terms of revenue – if you can’t make use of that source and it can, in fact be a detriment if mismanaged. Kristin Thompson shows, for example, that Peter Jackson was able to successfully leverage the Lord of the Rings book fandom through periodic exclusives released to theonering.net. [3] Likewise, and also after an initial period of frustration and hostility with the Harry Potter fandom, Warner Bros attempted to direct fan engagement through exclusives and giveaways to select fan websites. [4] Lionsgate has taken these earlier attempts to use and control fans and expanded upon them while also diversifying. Where New Line Cinema and Warner Bros incorporated the fan in a fairly superficial way and after fan engagement had made its presence known, Lionsgate made the fan the centrepiece of their campaign.

Lionsgate is not necessarily looking to bring in a mass audience, but an engaged one: a group of people who will buy into the apps, and watch the YouTube videos, and go to the Hunger Game Experience, and buy every new edition of the films. In the early days of the marketing campaign for The Hunger Games, they were not really all that innovative – certainly not in terms of transmedia storytelling or directing fan engagement. The online marketing started with fans themselves.

In 2011 a fan site started up offering a place for fans to login and interact with story elements as a member of Panem – the nation that is the setting for the Hunger Games. Nicola Balkind tells us that Lionsgate followed the Panem October site with one of their own, The Capitol, and began competing with the fan-run site. Eventually, the fan site was forced to shut down over a cease & desist order issued by Lionsgate and fans migrated over to the “official” website. There is some debate about how much of the Lionsgate-produced space was a copy of the fan space and how much of it was simply inspired by the work being done by unpaid fans. [5] Regardless the initial impetus, Lionsgate moved forward from that point on with the fan at the centre of much of their advertising.

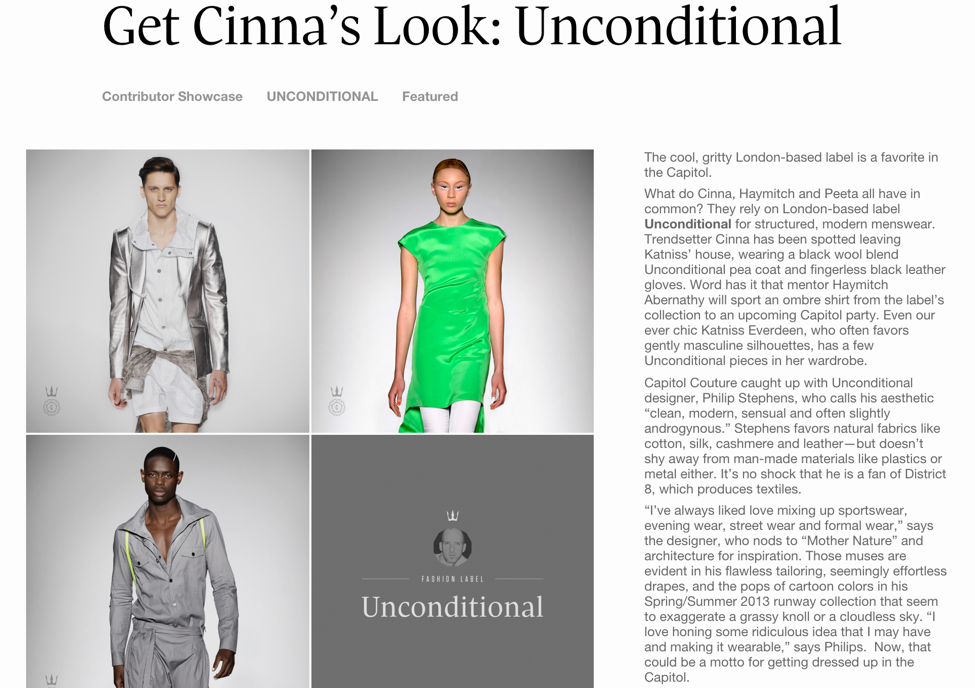

The marketing campaign for The Hunger Games series of films included a number of interlinked websites that released new content on a timeline that roughly followed the storyline in the films themselves. The content offered new information that blurred the lines of story and real-world elements including articles highlighting characters within the story and their real-world counterparts in, for example, the fashion world. The complexity of these websites also increased as the film series grew so that the space set up as the landing page for the fictional Capitol Couture magazine added more stories and gradually began to feature content in support of the in-film rebellion. Once the rebellion had made it to the magazine, it began to link to its own websites and propaganda in opposition to the ruling government content found on The Capitol website.

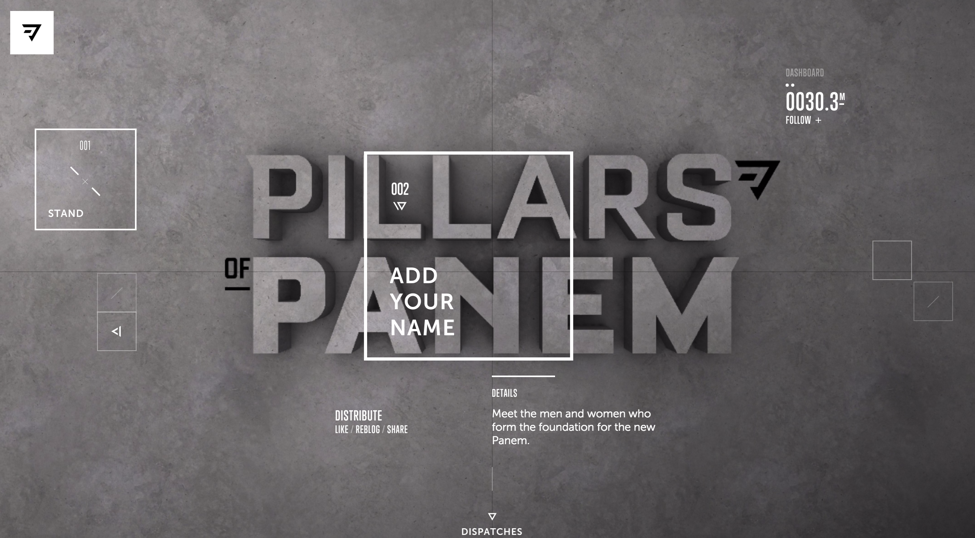

A casual fan of the series would potentially find all of the extra content and the blurring of storyline and reality difficult to follow, but an engaged fan would appreciate all of the new content aimed directly at them. The cultural cachet offered by their ability to parse the various ideas present throughout the promotional material, would appeal to many engaged fans. While this campaign may appear to speak only to a very small group of fans, just as Peter Jackson’s exclusives spoke directly to fans of The Lord of the Rings, Lionsgate combined this specific content with opportunities for fans to share information with a wider public. In addition to the now common fanart poster contests, fans were also encouraged to add their names to the Pillars of Panem, thereby signing on to join the revolution. They were also challenged to share trailers and other video content with their own social media networks in a competition for number one fan.

This type of promotion uses paratextual material that extends the film story while awaiting new installments in the series. The real power of such a campaign, however, lies in the free labor provided by fans in sharing content with a wider audience. What remains to be seen is whether this direction will be profitable and if corporations can sustain and contain a top-down creation of fandom when conflict arises between producer and audience. In the meantime, remembering that Lionsgate is a special case due to their position as a mini-major studio and the interest in employing a dedicated fan audience is not a new concept in any form of content distribution, I still think we can see that the desire to consider the fan as a separate demographic that can drive both sales and general audience purchasing trends is something with which the film industry is currently experimenting.

Image Credits:

1. Shut up and take my money!

2. Author’s screen grab

3. Author’s screen grab

4. Author’s screen grab

5. Author’s screen grab

Please feel free to comment.

- Tiziana Terranova “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy” Social Text 63 vol 18, no 2, Summer 2000, pp 33-58. http://web.mit.edu/schock/www/docs/18.2terranova.pdf. [↩]

- Abigail De Kosnick “Interrogating ‘Free’ Fan Labor” Spreadable Media Web Exclusive Essay, http://spreadablemedia.org/essays/kosnik/#.WmYy5JM-dAY. [↩]

- Kristin Thompson, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood, University of California Press, 2007. [↩]

- Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, New York University Press, 2006. [↩]

- Nicola Balkind, Fan Phenomena: The Hunger Games, Intellect, 2014. [↩]

There are a lot of good points being made in this article, and the questions raised about fan labor, intellectual property rights, and the ensuing tensions between producers and consumers surrounding transmedia are all important things to be considered in this new age of media consumption. I do believe, as stated above, that in a majority of instances, fan labor fuels the ideations behind spaces for transmedia and as a result (similar to The Hunger Games and Lionsgate example), these ideas become appropriated and commodified by corporations. Some argue this as the right of a conglomerate, especially if a series or campaign for the content has already been established, but how far should these rights be extended? Is it actually Lionsgate’s right to imitate a fan site, and then move to have the original shut down just because they gave birth to the story world that inspired said site? Furthermore, is the fan that created the original site really not entitled to a percentage of the profits Lionsgate is now reeling in from their own site? One of the pro’s of this digital age is the common place access it provides to media development, exhibition, and distribution, but it seems that corporations are constantly looking to challenge these freedoms. With the changes in our current mediascape, the FCC also needs to put new laws in place that will address such issues, otherwise these situations will continue to persist; and should there be nothing in place to check the exploitive powers of media corporations, media lawmakers will find themselves behind the curve digital/virtual vertical integration.

You don’t have to go to a fancy tasting event—set out a variety of wines, whiskeys, cheeses, or chocolates.