Listening—Finally—to Soundtrack Albums

Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University

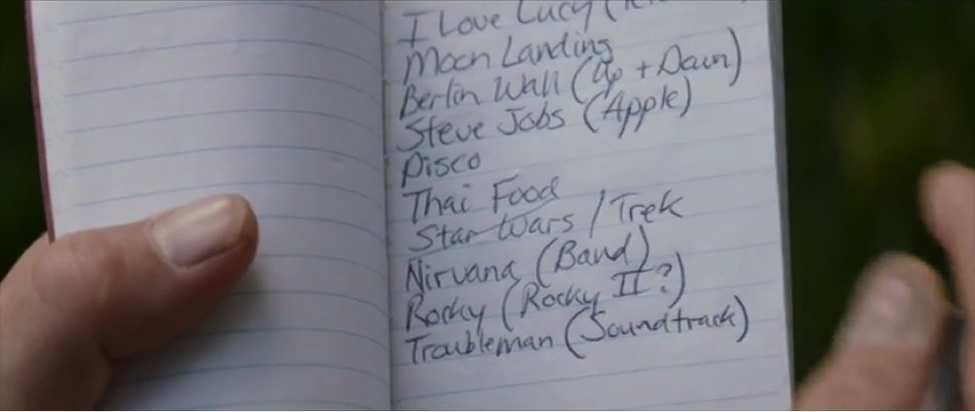

This is a list, or, more accurately stated, the image of a list, of perhaps the most important texts and cultural developments between World War II and the first decade of the 21st century. It appears on screen a few minutes into Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014). Each item here is worth considering, and we might question each item’s place here in lieu of other events, texts and signifiers.

My interest is in the final item: the Marvin Gaye soundtrack album Trouble Man (1972). In this first column I want to assert that the soundtrack album, can, and should, be thoughtfully considered by any scholar who will admit to owning, or listening regularly, to one. That likely means anyone reading this, and many of your friends.

Though many films and television shows promote their own ancillary products — action figures, t-shirts, soundtrack albums, plush toys, sippy cups — it is unusual for one film to promote the soundtrack album of another. And though the “Trouble Man” single appears on the Captain America: The Winter Soldier soundtrack album, Disney does not stand to profit from Trouble Man album sales.

In this moment, a Disney film does more to promote the idea of soundtrack albums as significant cultural objects than most works of media scholarship of the last several decades. In this scene, a summer blockbuster acknowledges the importance of one of the most ubiquitous, but least analyzed of all media paratexts, despite its apparently matching Jonathan Gray’s welcome call for an “off-screen” studies. [1] Here, within a superhero film, is at least the suggestion that soundtrack albums are meaningful. Almost 20 years ago, Jeff Smith asked: “What do fans derive from listening to soundtracks? Is it merely the chance to relive a pleasurable cinematic experience or does a film’s music relate to fans on some other extratextual level?” [2] Though some popular writing has recently considered soundtrack albums, Smith’s important questions have largely gone unanswered. [3] But let’s back up.

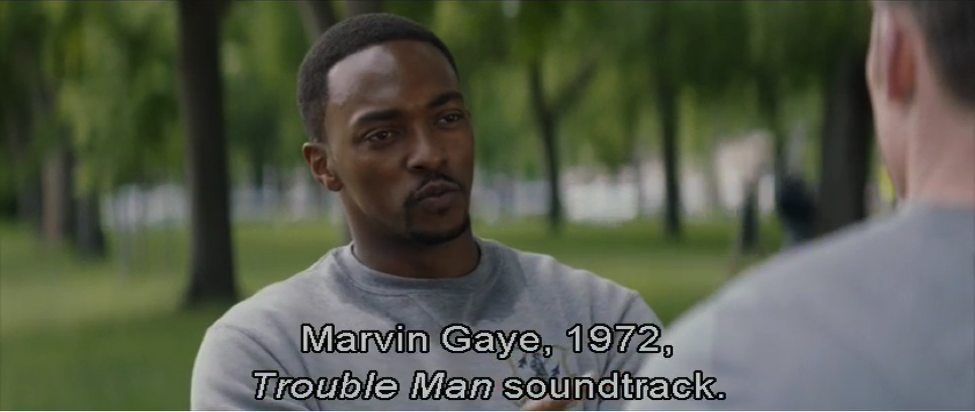

In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Sam Wilson (Anthony Mackie) and Steve Rogers (Chris Evans) meet while jogging on the Mall in Washington, D.C. Wilson knows that Rogers is also Captain America and was encased in ice for decades (awaking at the end of the previous Captain America: The First Avenger [2011]). Wilson wants to give Rogers guidance that goes beyond what he might learn from searching the Internet for information about the missed decades.

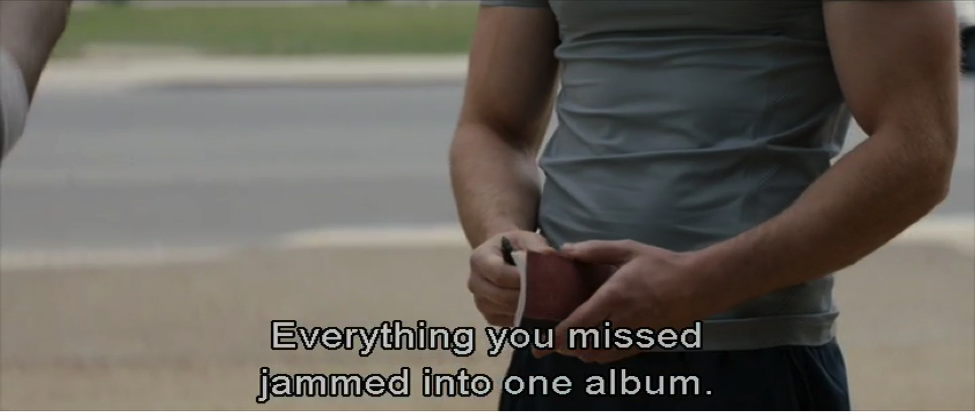

This is also clearly a gesture that a number of other well-meaning folks have undertaken. Rogers immediately replies, “I’ll put it on the list,” and documents the recommendation. Possibly others have made strong endorsements of particular items or ideas, but Wilson’s “Everything you missed jammed into one album” is a bold statement.

Please look again at the list Rogers is creating (scroll up if necessary). Admittedly, the list may cover multiple pages that remain unseen. But what we can see is striking: the list is dominated by pop culture material. The only items of a “historic” nature (the moon landing and the Berlin Wall) will almost certainly be experienced by Rogers not as history but instead as media events. Beyond these topics, the culinary arts are included, television is represented by I Love Lucy, Star Wars and Star Trek remain locked in their eternal struggle, and disco and Nirvana cover the music Rogers has missed. The presence of Trouble Man just below Rocky (1976) and Rocky II (1979) perhaps signals that the album will act as a corrective to the racial politics offered by those films. Rogers has mistakenly written “Troubleman” as a single word, but his awareness of Steve Jobs and Apple will, we can hope, allow him to find the album via iTunes.

Most importantly, Rogers has correctly labeled the item a “soundtrack,” just as Wilson carefully stated. Note that Wilson makes no effort to recommend the film which Gaye’s album would conventionally be said to “accompany.” The album, and not the film Trouble Man, is the text which is promised to contain “everything.” [4] Trouble Man is, not surprisingly, the only soundtrack album on the list. But it stands in pretty well as the single representative of this media type, not simply because of its quality as popular music, but also for the way it mixes instrumental tracks with songs foregrounding Gaye’s voice and lyrics.

Trouble Man might not explain decades of American culture, or even the single year of its release. It may not do any better in orienting Rogers—or the audience—than any of the other texts and topics in the list. But the idea that a soundtrack album has this potential is provocative. And perhaps even radical.

In media and popular culture studies it often (thankfully) is a given that television programs, films, music videos, comic books, gifs, and video games merit close analysis. Yet soundtrack albums are all too often dismissed as cynical attempts by massive corporations to extract more money from a duped public. Dazzled by a film’s logo and poster image on an album cover, the film-drunk teen buys the 8-track, LP, or CD and is saddled with music that is not even featured within the film itself. The horror. But media fans are not, and have never been, victims.

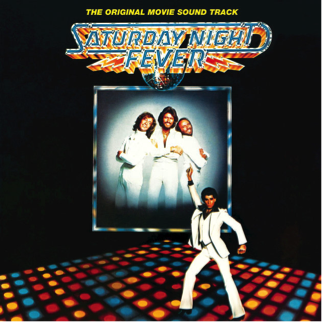

I would argue that Rogers’s list should include more soundtrack albums. Among other reasons, some of the best-selling albums in history are film soundtrack albums. The Saturday Night Fever (1977) album can help with disco and the 1970s more generally, everyone should hear Whitney Houston covering “I Will Always Love You” from The Bodyguard (1992), and Purple Rain (1984) is, well, Purple Rain.

These albums, Gaye’s Trouble Man, and countless others, do not merely support or promote the films listed on their covers. To suggest they do is to dismiss their contents as music, to disregard this cluster of audio texts as a (potentially) coherent whole, and doubt the seemingly simple notion that soundtrack albums create meaning whether or not the user has “seen” the film.

Though the record industry reports annually that album sales are “down” in the face of streaming services and YouTube postings, soundtrack albums continue to circulate. And soundtrack albums are still quite capable of being the top seller in a given year, with High School Musical (2006), High School Musical 2 (2007) and Frozen (2014) topping sales in their year of release. To study soundtrack albums is certainly to study synergy, marketing, and mass culture, but these texts invite analysis that crosses disciplines.

Film soundtrack albums are ubiquitous, and hiding in plain sight. We pull them up on YouTube, select them from streaming services, play them on turntables, cassette decks, and 8-track players, use them as workout music, allow them to engulf us in aural nostalgia, use them to set a variety of moods, and take advantage of their ability to provide access to a diverse range of artists in manageable servings as though Wim Wenders has made us a personal mixtape.

With these columns, composed in response to Flow’s invitation to explore media and culture, I hope to begin a conversation about soundtrack albums. I am also, with my colleague Laurel Westrup, editing a collection of new essays on soundtrack albums. This work has put me in contact with scholars trained in a range of disciplines who agree that studying soundtrack albums, and analyzing them as albums, is a good use of intellectual labor. My work here and elsewhere intends to build on and expand the foundation laid by a number of scholars and suggest new avenues, and texts, that we might explore. [5] It is time to listen, finally, carefully, to soundtrack albums.

Image and Video Credits:

1. Author’s screen grab

2. Author’s screen grab

3. Author’s screen grab

4. Main Theme from Trouble Man on YouTube

5. Saturday Night Fever Soundtrack

6. Purple Rain Soundtrack

7. The Bodyguard Soundtrack

Please feel free to comment.

- Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: NYU Press, 2010). [↩]

- Jeff Smith, Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music (New York: Columbia UP, 1998): 233. [↩]

- The A.V. Club series, “Soundtrack of Our Lives” https://www.avclub.com/c/soundtracks-of-our-lives; Clare Nina Norelli, Angelo Badalamenti’s Soundtrack from Twin Peaks (New York: Bloomsbury, 2017). [↩]

- Wilson could equally have advocated for the 2012 two-disc 40th anniversary edition, which might contain even more of “everything.” [↩]

- Smith has partially responded to his own questions with essays such as “Selling My Heart: Music and Cross-Promotion in Titanic” in Titanic: Anatomy of a Blockbuster, eds. Kevin S. Sandler and Gaylyn Studlar (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1999) 46-63. Other important discussions of soundtrack albums include K. J. Donnelly’s The Spectre of Sound: Music in Film and Television (London: BFI, 2005), especially chapter 8, “Soundtracks without Films,” and Lee Barron’s “‘Music Inspired By. . .’: The Curious Case of the Missing Soundtrack” in Popular Music and Film, ed. Ian Inglis (London: Wallflower, 2003): 148-161. [↩]

Great post! I look forward to following the rest of the series and I’m kicking myself that I didn’t submit an essay to the edited collection.

The Captain America example brought to mind another recent representation of soundtrack fandom. In Parks and Recreation’s season five episode “How a Bill Becomes a Law,” April Ludgate peruses Ben Wyatt’s CD attache case and ask him why he has so many soundtracks. He responds: “I kind of look at it like it’s your favorite directors making a mixtape just for you.” I find Ben Wyatt’s soundtrack fandom instructive for two reasons. First, his answer minimizes music supervisors’ contributions to soundtracks. Second, his fandom is generational. He owns the soundtracks for 90s films like Singles, Grosse Pointe Blank, and Pulp Fiction. In some sense, Wyatt’s soundtrack fandom further advances his nerdiness as a key character trait. But it also speaks to a generational divide between him and April. These soundtracks represent performances of curation and generic affinities that are of their time. Singles is a document of grunge’s fleeting popularity, Grosse Pointe Blank trades in new wave nostalgia, and Pulp Fiction puts surf rock in dialogue with lounge and funk in post-modern fashion. Ben, a Gen Xer, came of age at a time when music fandom relied upon materiality. Ben listens to music on CD (and on vinyl, as we discover in a later episode when he deejays Pawnee’s high school prom). April, a millennial who likes Neutral Milk Hotel and novelty records played at the wrong RPM she streams off YouTube, grew up with the Internet and cobbles together her taste from what she finds online.

These observations lead me to two questions.

1. Have we done enough in media studies to heed Jeff Smith’s call to take the music supervisor seriously?

2. How does the soundtrack document and respond to format changes over time?

Thanks for commenting and your kind words.

You’re provided another great example of audio-visual media diegetically acknowledging soundtrack albums and one that is new to me (thanks!). I don’t know that show well at all and hope this admission doesn’t result in my ejection from Flow.

I had to double check character names because I was really hoping that (someway, somehow) Ben he would be the Chris Pratt character and we could proclaim him the patron saint of 21st century soundtrack culture (between this and the Guardians of the Galaxy films). But, of course, your description of the character ruled that out immediately.

These are both important questions and ones that I’ll offer tentative responses to here (in part because I don’t know if I can give them real attention in the next columns. Or if I have answers at all).

1) The study of audio-visual media can still do more to acknowledge the work of sound creators and music supervisors. The discourse outside the smaller realm of sound and music studies seems, to me, to still dismiss music in film and TV as calculated efforts to make money. The “how” and “why” a piece of music ends up in audio-visual media is too often answered simply by checking who owns the company that produced the media text against the company that owns the record label, has the artist under contract, etc. But this study requires more careful study of the interactions between, and intersections within, media and music.

In terms of soundtrack albums, I would add that we need to take album producers/supervisors (organizers, negotiators, etc.) seriously. Based on your description, it seems that Ben, like lots of other folks, still suffers from the disease of auteurism. And while I think we should be skeptical of auteurism, auteurs in this area are perhaps one place to start a conversation. Claudia Gorbman has theorized “auteur music” and I think we can note that there are many soundtrack albums that at least claim to have been thoughtfully curated by the film’s director.

The promise of a Tarantino soundtrack album is that he has selected, organized and lovingly packaged a “mixtape just for you.” To hear Ann and Nancy Wilson covering Led Zeppelin on the Singles soundtrack is perhaps to get a taste of Cameron Crowe’s idea of heaven. And as that text’s liner notes say, “Soundtrack produced by Danny Bramson and Cameron Crowe.” In other words: soundtrack album created by the film’s music supervisor and writer/director/ producer. Artists like RZA (certainly an auteur) can also be mentioned here for crafting an album connected to a film written/directed by Tarantino or Jim Jarmusch.

2) Soundtrack albums, we might say, begin as 78s and end up as digital files and have been a core component of every format in between. Or, responding to the work of Katherine Spring and Rick Altman, we might say soundtrack albums truly begin as sheet music.

In the current moment soundtrack albums are being released as LPs, cassettes, CDs, and digital files (only my beloved 8-track remains in the dustbin of history). And the fact that the first 33 1/3 speed records were made for film screening is a fact that I think can’t be repeated often enough.

Your use of “document” I think is exactly the right word. I see more continuity than discontinuity in media history, both in terms of aesthetics and technology. But that does not mean format changes can be ignored. Soundtrack albums should be studied in terms of medium specificity. Trouble Man is the same on YouTube as it is on an LP. And yet it is not the same. I plan, in at least one of the next columns, to consider audio cassettes (and least briefly). But I can’t adequately answer your question here or in a future column. There is much work to be done to incorporate soundtrack albums into the discourse on audio formats and technologies.

Pingback: What is a Soundtrack Album? Or, Spot the Soundtrack Album Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University – Flow

Thanks for kicking off this conversation, Paul!

I think the question of authorship is an interesting one, especially with regards to Singles. You’re right that Crowe has taken authorship over the album, both in its original incarnation and in its recent re-release. In the press release for the album’s reissue in 2017, Crowe presents the album, as he has frequently done in the press, as a mixtape and an “anti-soundtrack” (http://www.legacyrecordings.co.....oundtrack/). I think these comments are meant to deflect the occasional critique that the album was a cynical attempt by Hollywood to cash in on the Seattle scene, though of course anyone who was paying attention knew that the film (and the soundtrack album, for that matter) were largely complete before any of the bands hit it big–before there was an (inter)nationally known “Seattle scene.” And let’s not forget that Crowe was famously the boy wonder of Rolling Stone (not to mention married to Nancy Wilson), so he had some musical cred going in. But I think the album “works” to a large extent because Crowe allowed the artists to exercise a degree of ownership over the material on the album. Chris Cornell reportedly suggested that Crowe check out Smashing Pumpkins after Soundgarden had played a show with them in Chicago, and his own song, “Seasons,” was part of a joke project he recorded as the Matt Dillon character, Cliff Poncier (called the Poncier EP, it was released on CD for Record Store Day 2015 and is now included as a bonus feature on the deluxe re-release of the Singles album).

So, yes, Crowe is definitely a curator, if not an auteur, of the Singles album. But so are the artists on the album, many of whom introduced Crowe to others in their orbit and took an active role in shaping the album.

And Alyx, I think you’re right to raise the role of the music supervisor, which the scholarship has definitely not addressed fully enough. In the case of the Singles album, Bramson’s role, according to Crowe, was primarily technical: he secured rights to the music (no easy feat: they got a Jimi Hendrix song!). It’s unclear to me how much of a role he played in choosing songs for the film or the album, though this process was surely collaborative to some extent. My sense is that there’s a lot of variation in the music supervisor’s role in constructing the soundtrack album, but it’s a great direction for future research.

Pingback: Soundtrack Album Fandom and Unofficial Releases Paul N. Reinsch / Texas Tech University – Flow