“I Just Expect There To Be Some Trouble”: Boyz N the Hood and Racialization of Cinema Violence

Caetlin Benson-Allott / Georgetown University

Although there was relatively little cinema violence during the 1980s, the decade nevertheless changed popular perception of such incidents. Between 1979 and 1988, the US media largely forgot their fear of cinema shootings, or rather it was eclipsed by a larger moral panic over gang violence. Gang activity did increase in the US during this period, but media coverage exaggerated and sensationalized the problem, vilifying all African-American youth by association. As a result, reporters and even some reviewers began predicting cinema violence at films by and about African-American men. The 1979 incidents at screenings of The Warriors had been treated as horrific yet isolated episodes — isolated by their association with one inflammatory film. But between 1988 and 1991, a series of films were accused of soliciting violence by soliciting Black viewers. An entire audience group was both courted and criminalized in advance, so that when violent incidents did occur, they provided confirmation bias for further prejudice and disenfranchisement.

Colors (Dennis Hopper, 1988) was the first film to inspire sustained press coverage about the threat of theater violence. Its depiction of gang life in Los Angeles so alarmed the LAPD that they demanded a private screening approximately one month before the film’s release to determine its potential impact. Afterwards, LA Country Sheriff Sargent Wes McBride predicted that the movie would “leave dead bodies from one end of this town to the other… I wouldn’t be the least surprised if a shooting erupted in a movie theater.” [1] Colors opened without incident, but unfortunately, ten days later, David Dawson was fatally shot while standing in line for the film outside a theater in Stockton, California. Dawson was a member of the Crips, and his attacker, Charles Van Queen, was a member of the Bloods, a connection that was overplayed in the press to suggest that gang movies weren’t safe.

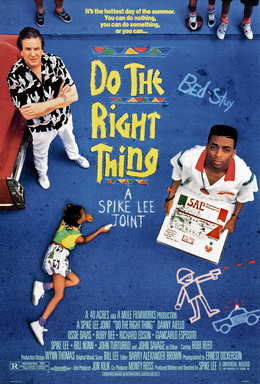

Not just gang movies, though — even serious dramas about racism and African-American disenfranchisement were critiqued for courting violence. Hence Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) was excoriated in New York Magazine for potentially inciting riots before it even premiered. Reviewer David Denby predicted that Lee’s film would “create an uproar” and warned that “if some audiences go wild, he’s partly responsible,” while columnist Joe Klein expressed hope that the film would open “in not too many theaters near you” because “black audiences” could “react violently” to its depiction of “a summer race riot.” [2] Jack Kroll of Newsweek also called the movie “dynamite under every seat.” [3] Needless to say, none of them apologized after Do the Right Thing ran without incident. Lee’s movie grossed over $27.5 million on a $6.5 million budget, sufficient success to warrant a cycle of similar films, albeit ones about black-on-black rather than interracial violence. The films of the “ghetto action cycle”—as Amanda Ann Klein and S. Craig Watkins call it [4] —continue Lee’s politicized violation of “a once-sacrosanct taboo against the portrayal of ‘negative’ images” of African-Americans by African-Americans. [5] These movies were likewise blamed for inciting violence despite their anti-violence messages of personal responsibility, messages that, ironically, downplay the larger social forces undergirding racist and gang violence in this country.

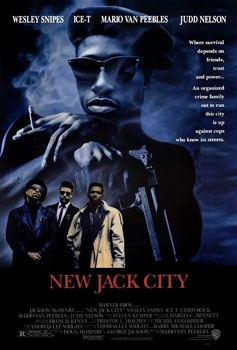

The first film of the cycle, New Jack City, premiered on March 8, 1991 — four days after news media unveiled video of Rodney King being beaten by LAPD officers. [6] Yet journalists failed to make that connection when reporting on a riot outside one of the film’s screenings. At the Mann Theater in Los Angeles’s Westwood neighborhood, ticket-holders became upset when denied seats to an oversold show. LAPD were called in, and King’s name became the rallying cry in a protest against institutionalized racism. Reporters only associated the Westwood riot with New Jack City, however, and with the death of Gabriel Williams at another Brooklyn screening. The New York Times translated these and other incidents into a fear-mongering think-piece about how a “Film on Gangs Becomes Part of the World it Portrays.” [7] The paper later granted producers Doug McHenry and George Jackson an op-ed to argue that “New Jack City doesn’t cause riots,” but the panic had been reborn. [8] After New Jack City, the press associated ghetto action films with cinema violence; as Singleton put it, they were “lying in wait” when Boyz N the Hood came out on July 12th of that year. [9]

Although Boyz N the Hood premiered at the Cannes Film Festival — where it received a glowing review from Roger Ebert — its US debut was marred by biased and inflammatory stories of cinema violence. During the film’s opening weekend, twenty of the 829 theaters where it played experienced some fighting or disorder. Shots were fired at cinemas in eight cities, and two people died: Michael Booth, at the Halstead Outdoor Drive-In in Riverdale, Illinois, and Jitu Jones, shot outside a downtown Minneapolis theater. [10] Riots and “melees” were also reported in Orlando and Tukwila, Washington. [11] The LAPD set up defensive barricades in Westwood, fearing a riot similar to the one that accompanied New Jack City (and evidently in denial about the latter’s correlation with the King video). Newspapers sensationalized all of these events; headlines like “Trail of Trouble for Boyz” and “ Film Opens with Wave of Violence” accompanied stories that belied the film’s commercial and critical success. [12] In one, an Atlanta exhibitor scoffs, “Frankly, I’m surprised they haven’t banned the movie,” while another quotes an anonymous Columbia executive lamenting, “Who will show these movies anymore?” [13] Even after the violence ended, newspapers continued to quote sources condemning Singleton’s movie as “just an excuse for getting rowdy.” [14] Like McHenry and Jackson, Singleton was called upon to publicly defend his film; he reminded reporters that cinema violence does not justify censoring filmmakers but is rather an “indication of the degradation of American society…a society that breeds illiteracy, economic depravation, and doesn’t educate its kids, and then puts them in jail.” [15]

Singleton rightly blamed the incidents at Boyz N the Hood — and Colors and New Jack City by extension — on the systematic dispossession of African-Americans, but this salient and important critique differs strikingly from the message of his film. Boyz N the Hood, like other films of the ghetto action cycle, stresses the individual’s personal responsibility to rise above unjust conditions. Its protagonist, Tre (Cuba Gooding, Jr.), avoids the pitfalls of early parenthood and drugs, which entrap his friends, because he has a strong father figure, Jason “Furious” Styles (Lawrence Fishburne), who counsels him on anticipating the consequences of his actions.

Furious also soliloquizes on how the impoverishment of black communities benefits white communities, but the film places its allegiances with Tre — who rises above — rather than with Ricky (Morris Chestnut) or Doughboy (Ice Cube), who cannot. As others have noted, personal responsibility is a politically conservative philosophy with high crossover potential for white audiences. [16] It is to Singleton’s credit that he did not continue this reasoning in press conferences or interviews. But the contradiction does matter, in no small part because some people used the content of films like New Jack City and Boyz N the Hood to interpret the violence that accompanied their premiers. “Personal responsibility” places blame with the shooter, the filmmaker, and sometimes the victim, but it does not ask viewers to question how mass disenfranchisement also breeds violence. It helps decontextualize cinema violence by aligning those involved with the pathologized or irredeemable characters who cannot or will not escape violence in the films. To be sure, most journalists and other pundits report on cinema violence before they’ve seen the films, but as the films’ anti-violence messages are subsequently marshaled for their defense, they point towards the “personal responsibility” of the perpetrators. Unfortunately, the social origins of cinema violence would not be considered by the mainstream press until the twenty-first century, when lack of adequate mental health care became one way of explaining why whites were killing other whites at the movies.

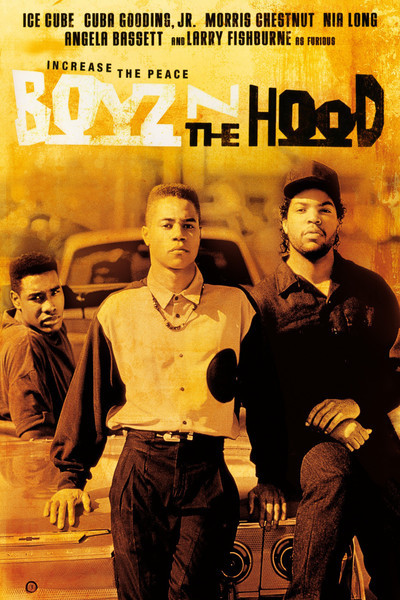

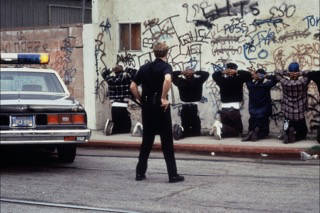

Image Credits:

1. Original poster for Boyz N The Hood

2. Danny (Sean Penn) Evaluates Suspected Gang Members in Colors (Dennis Hopper, 1988) (author’s screen grab)

3. Original Advertisement for Do The Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989)

4. Original Advertisement for New Jack City (Mario Van Peebles, 1991)

5. Furious Styles (Lawrence Fishburne) Advises His Son Tre (Cuba Gooding, Jr.) in Boyz N the Hood (John Singleton, 1991) (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- “Deborah Caulfield, “Colors Director Hopper Defends His Movie on LA Gangs,” Los Angeles Times March 25, 1988, Y18; “Gang Movie Colors Will Trigger Violence,” A1.” [↩]

- “David Denby, “He’s Gotta Have It,” review of Do the Right Thing (Universal film), New York Magazine, June 26, 1989, 53, 54; emphasis mine; Joe Klein, “The City Politic: Spiked?” New York Magazine, June 26, 1989, 14.” [↩]

- “Jack Kroll, “How Hot Is Too Hot; The Fuse Has Been Lit,” review of Do the Right Thing (Universal film), Newsweek, July 3, 1989, 64.” [↩]

- “S. Craig Watkins, “Ghetto Reelness: Hollywood Film Production, Black Popular Culture, and the Ghetto Action Film Cycle,” in Genre and Contemporary Hollywood, ed. Steve Neale (London: British Film Institute, 2002), 236-250, quoted in Amanda Ann Klein, American Film Cycles: Reframing Genres, Screening Social Problems, and Defining Subcultures (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2011), 139.” [↩]

- “Salim Muwakkil, “Spike Lee and the Image Police,” Cineaste 14, no. 4 (1990): 35.” [↩]

- “Laura Baker, 7” [↩]

- “Seth Mydans, “Film on Gangs Becomes Part of the World It Portrays,” New York Times, March 13, 1991, A16. ” [↩]

- “Doug McHenry and George Jackson, “Missing the Big Picture,” New York Times March 26, 1991, A23.” [↩]

- “Robert Reinhold, “Near Gang Turf, Theater Features Peace,” New York Times, July 15, 1991, A13.” [↩]

- “John Lancaster, “Film Opens With Wave of Violence,” Washington Post, July 14, 1991, A1; “Minneapolis Youth Second Victim of Violence at Film Showing,” New York Times, July 19, 1991, http://www.nytimes.com/1991/07/19/us/minneapolis-youth-2d-victim-of-violence-at-film-showing.html. ” [↩]

- “Mike Williams, “Boyz N the Hood Violence Subsides,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, July 15, 1991, A3.” [↩]

- ““Trail of Trouble for Boyz,” Hollywood Reporter, July 15, 1991, 6; Lancaster, “Film Opens With Wave of Violence,” A1.” [↩]

- “Norma Wagner, “Atlanta-Area Theaters Beef Up Security for Boyz’ Showings,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, July 14, 1991, A6; John Lancaster, “Film Opens With Wave of Violence,” A1.” [↩]

- “Williams, “Boyz N the Hood Violence Subsides,” A3.” [↩]

- “Andrea King, “Columbia Backing Up Its Boyz,” Hollywood Reporter, July 15, 1991, 6. ” [↩]

- “Kenneth Chan, “The Construction of Black Male Identity in Black Action Films of the Nineties,” Cinema Journal 37, no. 2 (1998): 35-48.” [↩]