The Visual Discourse between Hammer Horror and Showtime’s Penny Dreadful

Garret Castleberry / Oklahoma City University

The Horror-Drama TV hybrid has emerged as a culturally resonant television sub-genre in recent years. From Fear The Walking Dead, American Horror Story and Bates Motel to Hannibal, The Following, and Scream Queens, the televisual landscape now produces a year-round horror-programming continuum that stretches from traditional networks to cable. While HBO’s Oz arguably originated authentic body horror for subscription TV audiences, with plenty of spooky from The Twilight Zone to Twin Peaks preceding, Showtime entered the competitive fray with the sub-genre period horror drama Penny Dreadful (2014-present). While not the first horror series to embrace temporality as an invisible horror convention, Penny Dreadful revisits modernity’s mythologized decade of transition, the 1890s. This period of Western history is quintessential to gothic horror conventions and cultural anxieties aplenty, mythologizing the final years of Victorian era London at the dawn of the twentieth century. Narratives of this time often visualize Western history as encapsulated by themes of British Imperialism and London, still the apex global city renowned for its high- and low-culture. Deep-seeded sociological and intercultural themes conflict beneath London’s surface, including empires in twilight and the stress-and-strain of prolonged hegemonic control over industry and trade. The new century will inevitably bring about great change while the past cannot stay buried forever. Such was a time when sensationalized mysteries and salacious murders and serialized storytelling captivated the collective consciousness and drove society’s social discourse…does this turn of the century description evoke familiarity?

(De)Coding Visual Discourse Analysis

In Visual Methodologies, Gillian Rose conjoins the language of Foucault, Freud, and others to present a model for discourse analysis. For Rose, discourse “refers to groups of statements which structure the way a thing is thought, and the way we act on the basis of that which shapes how the world is understood and how things are done in it.” [1] As a result, “Discourse also produces subjects,” which we might read in layers as viewers of a program or text, critics and bloggers that circulate paratexts, or fans and aca-fans that negotiate meanings across the bridges of various media(s) and mediums. For texts like serialized horror TV series or anthologies, their very postmodern ontologies toward attaining-retaining-building-sustaining audience circulation depends upon a certain amount of overt and covert intertextuality, or the ways texts reference former texts to greater and lesser degrees. Rose links the relationship between discourse and intertextuality, where “social production” also needs addressing “questions of power/knowledge” and “cultural significance.” [2] Keeping these critical discourse themes in mind, I consider the conventional canon of Hammer’s gothic horror sub-genre and assess through comparison how these texts constitute a visual discourse that has been replicated and re-imagined, imitated and innovated in Showtime’s serialized televisual horror drama Penny Dreadful.

Visual Iconicity of Hammer Horror in Penny Dreadful

In Popular Culture, Marcel Danesi observes how, “In typical postmodern fashion, the [contemporary drama] series has a few good guys, a few bad guys, and in between a lot of question marks. The audience is suspended in the simulacrum,” [3] By simulacrum, Danesi refers to the number of texts that stretch back decades if not centuries or longer, from which audiences no longer recognize. This is important for understanding that viewers can still appreciate a series like Bates Motel or Penny Dreadful without even recognizing the source material it draws from. More than simply deepening an appreciation for core themes and conventions, borrowing from discourse analysis highlights ways in which intertextuality, social production, and assessing relationships between power/knowledge help elevate a text’s cultural timeliness or what I might call its ideological imprint.

Several genre themes recurrent among Hammer’s gothic horror films include dramatic juxtapositions between large versus small exteriors and interiors, characters haunted by past actions, social situations of upright moral integrity versus uninhibited carnal instinct, tensions between sexual repression and metaphorical expression, and the occult actions of the socially privileged rooted in motivations toward greed and power. Hammer Films, when functioning in peek form within the Victorian gothic horror sub-genre, possess a liminal status between old-fashioned aesthetic (e.g. conservative ideals) with climactic moments of shock violence and visual sensuality (e.g. progressive politics).

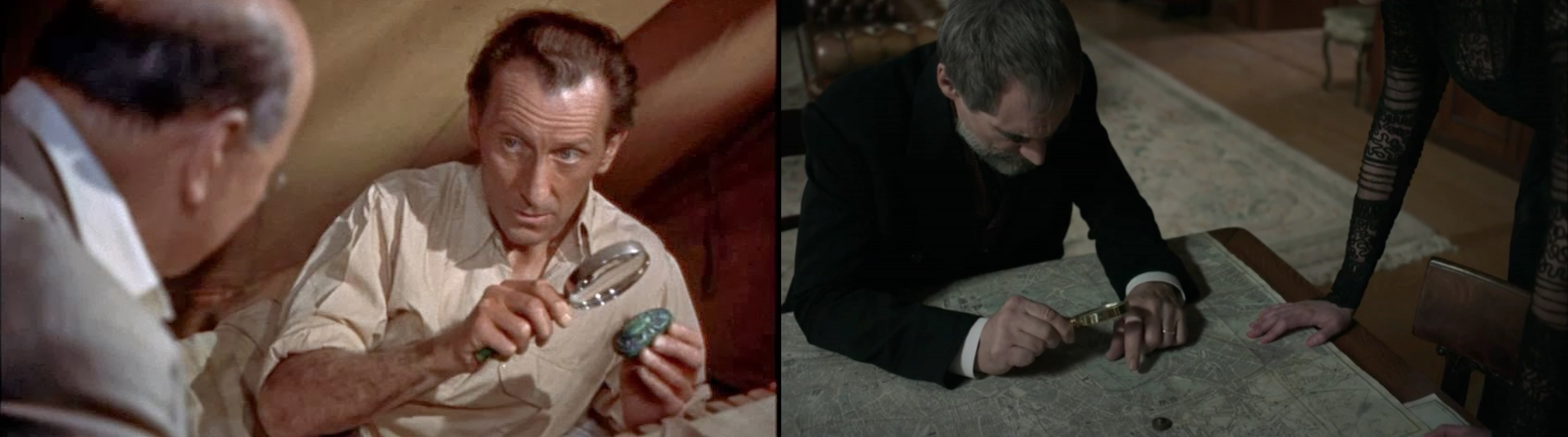

Interviewing with The A.V. Club, showrunner Bryan Fuller talks at length about how Hannibal worked to evoke the “visual iconography” of Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs, not really functioning as “homage” so much as a conjuring of the visual iconicity of the films that inspire their series. Similarly, Penny Dreadful feels invested in Hammer Horror’s lush gothic visual history. While many Hammer films were not connected in terms of continuity and world-building, they share aesthetic production designs, suggesting each could occur within the same macabre universe. Frequent carryovers of stock character actors like a Peter Cushing or a Christopher Lee communicate a kind of iconic assurance that some mystical mayhem may soon unfold. Similarly, Penny Dreadful constructs a cast that gradually comes together just as their respective monstrous origins slowly reveal. Such gradual pacing suggests another unmistakable trademark genre convention with the Hammer Horror franchise.

In interviews, creator-writer John Logan and other production staffers articulate the necessity that Penny Dreadful closely align with Victorian environment and gothic literary conventions. Yet as a televisual medium with increased focus on visual storytelling, which holds greater potential to unlocking nontraditional and international viewers, what is onscreen before the eye yields optimum persuasive appeal and aesthetic allure. Consider how closely key visual “reveals” of monsters and macabre imagery recalls the lush Technicolor vibrancy of Hammer Horror. The Hammer brand, like the Dracula of legend, finds rebirth and renewed potential for new audiences, fan audiences. As with the pagan followers of folklore, fandom minions brandish cultish reverence and devotion to the circulation of pop culture artifacts like Hammer Horror and now Penny Dreadful.

A Dreadful Conclusion on the Haunting Performance between Fan and Text

Showtime’s Penny Dreadful already boasts a prominent following with online devotees carrying the moniker “Dreadfuls.” In this new era of “Peek TV” where buzz carries cultural currency—which translates into economic currency in the form of life extension(s) for beloved televisual texts—followers perform ritual magic to ward off the plague of cancellation. Whedonites and Fannibals and Dreadfuls [Love]craft transmedia séances in the form of online petitions, polls, or Kickstarter-type funding apparatuses. The offering plate consists of Bitcoin and PayPal, the pagan temple only as large and as fast as a devotee’s high speed Internet can manifest. Indeed, the fan experience can become as performative as the text. Sensory data inspires feeling, which begets digitized social action. The ritual is not “going to the movies” and audiences assuredly no longer shriek in fear! at the horrors they see onscreen despite contemporary terrors having increased attention to detail with implausibly high production values. Genres are liminal creatures as well, morphed and hacked and reassembled Frankenstein monsters of their own creator’s making, abominations to Modernity’s laws of structure and order. Chaos is king and simulacrum is its business plan. But for Penny Dreadful at least, the past lies buried beneath the surface, bubbling up to rear its head and remind viewers of a previous cinematic, televisual, literary lifetime, haunting the text until its inevitable demise.

Danesi suggests, “The television text indeed developed into a simulacrum itself, indicating that it may have lost its cultural hegemony as a social text.” [4] Indeed, the fragmentation of channels, the modalities of viewing, and the temporalities of time-shifting reorganizes leisure culture that now extends outside of its formerly Westernized borders. This is a postmodern shift and a conflicted one at that. Technology, the historical boogey man of progress, in some ways function as a leveling of the cultural playing field on one hand while reinforcing cultural imperialist scripts on the other. Change can be horrific, traumatic even. It is no wonder our senses demand aversion through reanimations of the familiar and the foreign.

Image Credits:

1. Penny Dreadful logo

2. Hammer Productions logo

3. Floating eyes from The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958)

4. Penny Dreadful episode 4, “Demimonde” (author’s screen grab)

5. Peter Cushing in The Mummy (1959)

6. Penny Dreadful episode 3, “Resurrection” (author’s screen grab)

7. Christopher Lee in Dracula Has Risen From The Grave (1969)

8. Penny Dreadful episode 1, “Night Work” (author’s screen grab)

9. Library seance from The Devil Rides Out (1968)

10. Library seance from Penny Dreadful episode 1, “Night Work” (author’s screen grab)

11. Christopher Lee in The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

12. Penny Dreadful episode 3, “Resurrection” (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Rose, Gillian. (2007). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage. 142. [↩]

- Rose, 142, 147, 151. [↩]

- Danesi, Marcel. (2012). Popular culture: Introductory perspectives, 2nd edition. New York: Roman & Littlefield. 188. [↩]

- Danesi, 188. [↩]

I like to watch horror stories and horror movies. Mostly i watch horror movies with my friends in a dark room..But it is not good for the children under 12 age.. And i will say one word for this post” Awesome”

Films are stories about people, and visual effects are the ability to present this film to the public. I recently stumbled upon a student arthouse about the availability of information. They talked about the need to legalize such sites https://au.papersowl.com/. This movie hooked me. I think that young people should use the Internet as freely as possible.

Very interesting post. Horror movies are one of my favorite genres. But it is also important to write a good resume. If you are a nurse and are looking for a job then you need how to write a nurse resume. This is an easy way to find a job.