(Mis)Representing Black Sexualities: Madea versus MaDukes

Amber Johnson / Prairie View A&M University

Currently, there exists no safe space for discussing Black sexuality in mainstream media. Writers, directors, and producers continue to depict sexual stereotypes that limit the ways we view Black sexuality by portraying African Americans as deviant, inappropriate, hypersexual, and/or a-sexual. In this article, I focus on Tyler Perry and Aaron McGruder, two seemingly unrelated men brought together through sexual satire and speculation. I argue that both Perry and McGruder’s depictions of Black culture, sexuality, and gender are problematic and damaging at times.

McGruder’s cartoon, The Boondocks, courageously addresses politics, government, democracy, and race in America; however, his parodies of sexual desire fail to address complexity or the intersections of race, gender, and class, among other identities. Using satire in his episode titled “Pause,” Aaron McGruder insinuates that Tyler Perry is a gay drag queen through the character crafted in Perry/Madea’s likeness named Winston Jerome/MaDukes. McGruder criticizes the ways in which Tyler Perry enacts his perceived sexuality in secret, down low fashion utilizing his authority, power, money, religion, and theatrical performance as Madea. While Perry’s sexuality hangs in question during the episode, this article is not about whether Tyler Perry is gay. That is not my concern. Instead, I question the portrayals of Black sexuality by both McGruder and Perry. While Perry purports to tell stories that are uplifting and life-changing for his audience, he reifies certain stereotypes that further restrict the ways we understand and consume Black sexuality.

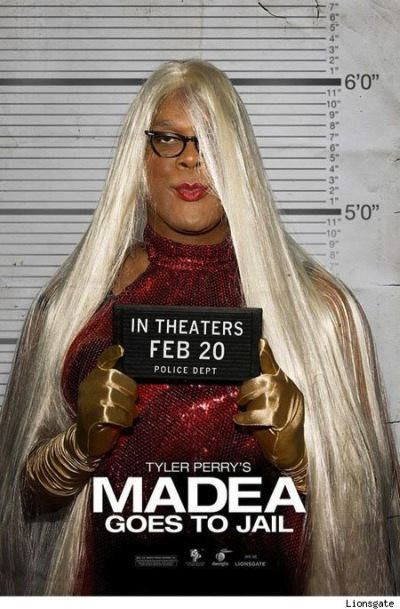

Madea Goes to Jail presents the first full narrative of Madea. Through newspaper clippings, headlines, photomontages, business cards, mugshots, and playbills, Perry brings Madea’s sexual and criminal past to the audience. Hailing from a long line of stripping, criminality, and prostitution, each mug shot captures Madea sporting exaggerated make-up, big wigs, sequined outfits, school-girl outfits, and other shiny ensembles that resemble a drag queen at the ball. While “She’s a Lady” flow from the speakers, we see images that suggest a very un-lady like grandmother based on Madea’s unconventional performances of hypersexuality and normative masculinity.

Tyler Perry purposefully plays to masculine/feminine gender roles through the Madea characters. Each image adds substance to the sexual and criminal narrative of Madea, and creates a masculine versus feminine dichotomy for her character. She is either associated with sex and sexuality, or fighting, strength, and aggression. She may refer to herself as a woman, but others call her a man, further explicating that using the song “She’s a Lady” as the backdrop of her narrative is not only a play on the lack of normative feminine characteristics, but also a lack of female genitalia. What this does in terms of Black women’s sexuality is reduce our behavior to that of deviance, hypersexual, and uncivilized, or what Patricia Hill Collins refers to as controlling images. The available narratives for Black women are already limited, Madea’s performances do not add to those representations, but instead mock them. Mcgruder introduces another facet of Madea by exploiting Perry’s performance in drag.

While Perry only narritivizes Madea’s sexuality in his works, McGruder brings that narrative to life in first person form through MaDukes. McGruder’s satire of Perry/Madea as Winston Jerome/MaDukes misrepresents the down low as a negative, shameful, and deviant space due to an insensitive reading of the intersections of race, class, and gender. Both representations fail to address the complexity of black sexuality. While countless scenes from “Pause” illustrate the limited depictions of Black sexuality, I want to focus on two scenes specifically, “It’s Alright to Cross Dress for Christ” and the final scene.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show parody focuses on the embodied performance of drag. The audience witnesses Winston Jerome in his private time away from work dressed in MaDukes’ fat suit, but not necessarily as MaDukes. Winston Jerome is a drag queen, on and off camera. The revamped lyrics ignite images of bananas, cream, unicorns, and wet dreams. Winston Jerome and his cast of men and women dance seductively to the music, swaying their hips and gyrating for, presumably, Christ.

Much like Winston Jerome delivering the last line with a pelvic thrust to the buttocks of a male cast member, McGruder blatantly connects Tyler Perry with drag and homosexuality in this scene. The images and the lyrics are no longer suggestive, but outright accusatory. This scene portrays Winston Jerome as gay, in denial, and willing to blame his deviant behavior on the fact that Jesus is behind his performance, literally and figuratively.

Aaron McGruder’s use of Time Warp and Sweet Transvestite capture the full critique of hiding behind a religious organization to perform homosexual acts and posits that Tyler Perry produces his works so he can perform the Drag Queen he is without being considered homosexual. He is simply a man performing his work for Jesus and to spread a message to women.

In this final scene, Granddad is able to confirm his heterosexuality through derogatory comments towards sexy women, denying Winston Jerome’s advance, clowning Winston Jerome for being a homosexual, and, ultimately, by utilizing the term “no homo.” While he may not have been able to get with beautiful, “big-tittied” women half his age, he does get to redeem his masculinity in hegemonic ways. While Huey, Riley, and Granddad may have a happy ending filled with resolution and redemption, the episode’s ramifications complicate DL discourse and Black sexuality.

To pit “Pause” and Tyler Perry together may seem accusatory, but that is not the point here. I am not arguing that Tyler Perry is gay or on the DL, or that Aaron McGruder is homophobic. Instead, I argue that current DL discourse results in the further ostracizing of all Black men and more dissent between Black men and women. While it does create space for dialogue, the dialogue ensuing is not necessarily productive in terms of sexual health in Black communities.

Discursive constructions of the down low presume that DL men participate in heterosexual relationships while sleeping with men discreetly, casting a heteronormative hue over the DL. Reasons for being on the DL are more than one can list here, and do not all rely on heterosexuality.1 The DL categorizes more than a space for men to be heterosexual in public and queer in private; it is a much more complicated construct.2 It is an alternative construct for enacting quare sexuality without having to adopt white, normative, homosexuality. As McCune poignantly suggests:

The DL may offer an alternative to the closet—a space where much more happens than black men having sex with wives/girlfriends while having sex with other men—where men actively negotiate issues of race, gender, class, and sexuality. Indeed, if we must accept the idea that black men do play, dwell, or reside in the closet…the closet’s entanglement with ‘coming out’ often jeopardizes its utility for men of color. As one DL man told me, ‘There is no closet for us [black men] to go in—neither is it necessary to come out.’3

Unfortunately, popular culture and text have created a negative depiction of the DL that does not take into account race, class, or gender differences. Instead, it dehumanizes black sexuality from multiple angles. One need not look much further than popular rhetoric. From Ebony and Essence magazine, to the Oprah show, black men have been told, “come out of the closet, out of the basement. Down-low Brothers, face up to who you are, and let us live!”4 They have been blamed for ruining our lives, living dangerous lies, and breaking up families.5 They have been accused of ruining entire communities.6 Pop culture labels DL men selfish, accuses them of putting their deviant desires ahead of their families, victimized wives, and children. This discourse creates a strangling reality that can further deter Black men from being comfortable about performing sexuality7 , and forcing them to participate in a type of queer world-making that renders itself invisible to heteronormative constructs.

Black sexuality stands stranded under the guises of deviance, hypersexuality, and disease. McGruder made a conscious decision to pit perceived closeted sexuality in the homophobic belly of Hip Hop and the Black Church. By using homophobic spaces to address homophobia, McGruder is able to draw forth a larger critique of mediated queer sexuality. However, McGruder is held hostage to many of the same dominant cultural symbols that we all fall victim to. His use of the master’s tool invoke (mis)representation of the DL while continuing his critique of closeted homosexuality within homophobic arenas. We must challenge our artists, writers, producers, and directors to create new images that reflect lived realities beyond stereotypes through a continued search for knowledge and understanding of multiple subjectivities that are constantly shifting.

Image Credits:

1. Screen capture from The Boondocks, Adult Swim

2. Madea Goes to Jail movie poster

3. Screen capture from The Boondocks, Adult Swim

3. Screen capture from The Boondocks, Adult Swim

- Boykin, K. (2005). Beyond the down low: Sex, lies, and denial in Black America. New York: Carroll & Graff. [↩]

- King, J. (2003). Remixing the closet: The down-Low way of knowledge. Retrieved May 2, 2011, from http://www.villagevoice.com/2003-06-24/news/remixing-the-closet/1/. Pg. 38-46.; Boykin, K. (2005). Beyond the down low: Sex, lies, and denial in Black America. New York: Carroll & Graff.; McCune, J. Q. (2008). “Out” in the club: The down low, Hip Hop and the architexture of black masculinity. Text and Performance Quarterly, 28, 298-314.; Hill, M. L. (2009) Scared straight: Hip-hop, outing, and the pedagogy of queerness. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 31: 1, 29 — 54. [↩]

- McCune, J. Q. (2008). “Out” in the club: The down low, Hip Hop and the architexture of black masculinity. Text and Performance Quarterly, 28, 298-314. [↩]

- Norment, L. (2011, May 16). The low-down on the down-low. Ebony. Retrieved from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1077/is_10_59/ai_n6132472/ [↩]

- The Oprah Winfrey Show. (2010a. October 7). Free from life on the down low. Retrieved from http://www.oprah.com/oprahshow/Free-from-Life-on-the-Down-Low. [↩]

- The Oprah Winfrey Show. (2010b, October 11). A Husbands betrayal: How his wife contracted HIV. Retrieved from http://www.chicagonow.com/blogs/ndigo-girls-and-toys/2010/10/oprah-guest-jl-king-tells-5-things-women-must-know-about-the-down-low.html [↩]

- Boykin, K. (2005). Beyond the down low: Sex, lies, and denial in Black America. New York: Carroll & Graff. [↩]