Revisiting Fandom in Africa

Olivier J. Tchouaffe / Southwestern University

In thinking about Aca/Fan, I begin with the match between cinephilia and self-fashioning and the ushering of a different paradigm of visual experience pulling away layers wrapped around notions that were once claimed as “Low-brow,” “Middle-brow,” and “High-brow” to flesh out a composite picture of what can called “No-Brow.” Hence, my usage of the term “No-Brow” is to argue how fandom studies are hollowing out terminologies such as “High-brow,” “middlebrow,” or “Low-brow,” and, in this sense, even kitsch can be granted artistic respect because distinction is not the primary aesthetic value but habitus which is the abilities of fans to mine deep into their cinephilia to self-fashion themselves overtime. It states the knowledge that subjectivities such as class, sex, gender or race are not necessarily predominant in the engagement with the texts because politics do not inform the context of reception as lived experience; habitus and self-fashioning do. Hence, the cultural entanglement with the text is too large to be reduced or essentialize to a particular subjectivity. The rapport with the text, consequently, is multi-sited and involves an infrastructure that combines a complicity between technology, media and the fans which taken together informs on the context of reception. This combo brings back the profane into the temple once reserved exclusively to the gods until Prometheus stole the fire from the skies. Thus, one can make the argument that Aca/Fandom is essentially a form of cultural anti-snobbism, partly, because the fans are deep into their own enjoyment to impose their wills on others. It is a horizontal relationship that assumes the multiplicity of ways of beings.

There follows the argument that “No-Brow” is linked to the rise of mass-media and modern development from which Africa has been left out. An aggregate argument can be made that, as a result of, different economic models, infrastructures, resources and capacities- deficit, in addition to, a lack of shared histories, and because the continent is largely known through anachronistic images of National Geographic and Discovery channels, all describing a place out of touch with big mass media megatrends and less likely to experience the modern fandom phenomenon as described by Henry Jenkins. These important factors may enshrine a narrative of disunity in fandom studies but that would be to ignore how notions of fandom circulate in places outside of the West. It begins with what Brian Larkin calls “the colonial sublime” which is how the introduction of railways, highways bridges and media technologies to create infrastructure which “refers to this totality of both technical and cultural systems that create institutionalized structures whereby goods of all sorts circulate, connecting and binding people into collectives.” He goes on to claim that the contradiction at the heart of the colonization where the colonial subject has to be “preserve” while at the same time being brought into the modern era through the “colonial sublime,” therefore, “railways, roads and broadcasting were erected to bring into beings a technological mediated subject proud of his past but exposed to new ideas, open to the education, knowledge, and ideas traveling along this new architecture of communication (2008, 6, 21 & 37). Thus, this colonial infrastructure was the beginning of a process of transculturation changing the continent’s cultural cartography. Hence, media studies must learn to problematize multilayered spaces of discourses ranging between the global to the local to understand media flows.

Along the same lines, the most important question we can ask regarding fandom in Africa is whether or not other forms of fandom can exist outside of the societal context theorized by Henry Jenkins. Along the same lines, is it possible that an alternative form of African fandom exists and that it reenacts, to some degrees, firmly established forms of American fandom including in its identity formation, cultural practices and socialization all entrenched in hyper-spaces such as fan clubs, fan zines and other media platforms. The accumulation of these forms of fandom’s cultural capital and creative interactions result on novel forms of performativities and relationships which transform and reconfigure the relationship between fans and creative industries into a relationship of creators and co-creators.

The application of fandom and its resources is not the same in all cultures, and within this context, African fans might not be recognized as legitimate fans, but the point of this piece is to demonstrate that there is, despite popular scholarship that seeks to isolate the African continent as a cultural backwater, an unifying figure of American domination of mass culture. This infuses my reading of Jenkins’ work with the knowledge that every society needs symbolic battles not only to define themselves but also to delineate what is legitimate or illegitimate in cultural interactions with others. My view of fandom goes beyond the immediate pleasure of the text and says something profound about the role of inter-subjectivities and social organizations. In this sense one can recognize some aspects of interactional sociology present in the work of others thinkers such as Erving Goffman, Michel de Certeau and Dan Sperber.

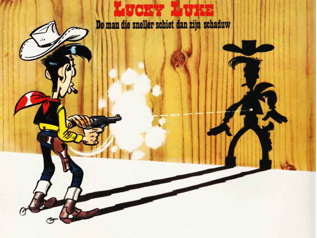

While in a discussion of fandom in Africa, I would like now to look at my own family which owned movie theaters and helped produce films in the West African countries of Cameroon. In addition, I would like to discuss my mother, Marie-Claire Tchouaffe, an executive in the country’s largest distributor of books, newspapers and magazines who made me highly popular in the neighborhood and turned me into a one-man library of sorts by regularly bringing home the cartoons of Superman, Batman, Spiderman, Mandrake the Magician, Tarzan, Akim, Zembla, and Flash Gordon, in addition to others impersonating Americans and almost unknown in the US, including, Blek the Trapper and Lucky Luke that I now regularly lend to my American friends for an unique view of their own culture from an outside perspective.

I grew up in a rich, inspirational and media saturated environment from which I saw firsthand the development of African fandom in relation to American popular culture. My grandfather, Jean Baptiste Tchouaffe, the family patriarch, also known by the name “Colt” from the Giuliano Gemma’s character in the Western Spaghetti “Arizona Colt” (1966), a testimony to his excessive fandom of Western films and Chinese Hong-Kong martial-art films as well. 1 Consequently, the most resilient images from my tender childhood are those from watching, mostly Westerns and Chinese Martial arts films, with my grandfather, while at the same time watching my father, Gilles Tchouaffe, labor in the 1980s and 90s to develop a respectable film industry in the country of Cameroon. These indelible images motivated me on a path of media- education since early on; I became aware that media narratives are more than entertainment. They help us make sense of our lives and generate codes of ethics, and sets values to live by. If there is something personal and familiar I bring to media studies, in this case, are the memories of my media-oriented family growing up under the influence of American and Chinese media in Cameroon.

Hence, being a fan is about pushing the boundaries of what is humanly possible. Heroes whether Superman, Batman or even the anthological Prometheus can be seen as redefining the limits of human potential since they are breaking into the final frontier, and in so doing, enlarging the scope of human knowledge and abilities. Perhaps, the most interesting thing about fandom is that it involves a mixture of technology, mythology, fantasy, and the drive to transcend borders, which is what had led me to Texas in the early 1990s, a place which in the eyes of my family was still very much like the wild West, and where many of my future American friends supposed I still had zebras, tigers and lions trotting around my backyard.

Knowing the details and profound logic of Batman or Superman, moreover, is a science and a language in of itself where notions of space and time, tradition and modernity are constantly intertwined and overlapping. Part of the core message is the love of seriality and the pleasure of anticipation. These different systems of writings and performance have something in common which at the core was the idea that the world of tomorrow will be a better and more tolerant place because the actions of these heroes increase scientific knowledge. Hence, fandom for me always was about open and unlimited spaces of possibilities where the grandeurs of human potential always asserted itself. Reading about Batman and Superman allow me to revel in all kinds of scientific absurdities while also allowing me better sense of the political and cultural environment of my own country Cameroon while growing up in the country under a dictatorship. It opened up my eyes providing me with a way to circumvent the mind-numbing local political propaganda by inventing an alternative world of unlimited possibilities.

As I continue to take note of the ongoing transformation of Superman and Batman, I am still baffled by cartoons like Blek the Trapper and Lucky Luke, the man who shoots faster than his shadow, and how both of them where representing respectively the tale of the struggle for American independence and the taming of the American wild West, as seen through the eyes of Italian and Belgian artists. These hand me down cartoons were sold to us in Cameroon as quintessential American stories and reveal how multi-layered complicated notions of fandom can seem since with these cartoons we have an Italian or Belgian perspective of American history recapitulated and passed on as a hybrid-sort of fandom to share with Africans. I always found it interesting that my American friends had never even heard of these characters who are supposed to be a great part of their stories, thereby, illustrating my point about complex layers of fandom.

To clarify, Blek, the Trapper and Lucky Luke represent a view of America refracted and reflected through European eyes, which as with the Spaghetti Western of Sergio Leone, reveal the worldwide appeal of myths involving the American West which itself can be seen as a substitute for a kind of eternal wild frontier. It is equally interesting while revisiting Lucky Luke to examine the debate about ethics around fandom. My enthusiasm nowadays is tempered by the clichés and stereotypes embedded in the cartoons even if they were created in good humor. While the description of colonial Brits in Blek the Trapper as “Red Lobsters” might cause to ponder about the origin of the famous seafood chain, the recurrence of Chinese as cunning and sneaky and of Mexicans as lazy and irresponsible and of the Blacks as darkies are unequivocally racist in nature, even though they are offset by Lucky Luke as a defender of the vulnerable. Thus, the grotesque depiction of minorities allows us to make a moral judgment about the relationship between representation and reality. These cartoons heroes depiction therefore even though they did not look like us, or move like us, and did not come from our culture but they did talk like us and they were always defending of the hopeless and the oppressed. You can feel the desire for justice and to make the world a better place by fighting evil on all fronts with the power of human potential. Thus, even though it was all fantasy and we knew all the codes, it was a convention we were happy to live by since it gave us hope.

Hence, fandom generally considered not to infiltrate Africa; but my childhood shows that both “No-Brow” and mainstream fandom did exist, a fandom sometimes from America itself, other times as seen through Europeans eyes, which even though it consisted of racial overtones and derogatory stereotypes, still provided us with the hope for a better life other belief in the triumph of liberty.

Image Credits:

1. Lucky Luke

2. Arizona Colt

3. Arizona Colt

4. Batman

5. Superman

6. Blek

7. Blek

Please feel free to comment.

- I went on to write my master’s thesis on the reception of Hong Kong films in Cameroon [↩]

Pingback: Special Issue: Revisiting Aca-Fandom | Flow