The Faces of Athletes

Markus Stauff / University of Amsterdam

The Faces of Athletes: Visibility and Knowledge Production in Media Sport

Markus Stauff / University of Amsterdam

While sport is often defined as, for example, the public display of physical exercise, in media sports we encounter equally often the public display of emotions. The visibility of the face is one of the decisive differences between the reception of sport in the stadium and in the media. Already in the 1960s the integration of faces of players, as well as those of the fans in the stadium, during the NFL broadcasts was thought to open the sport, defined as the realm of masculinity, to a female audience. It is no wonder then, with the realm of masculinity under pressure, that the esteem of faces and their expressions is observed with disapproval. The emphasis on the face is thought as a commercial media strategy that distracts us more and more from the real nature and meaning of sports. At the same time, emotions are often said to be one of the core features of sports; even more, sports is considered one of the last resorts of emotions and also the guarantor of authentic emotions that are not restricted by social norms of behavior. The face, then, is at the heart of sports’ cultural representation as it is at its margins, ambivalently connected to all that is thought to lie beyond true sports: advertising, star cult, personal biography, and so on. I want to argue that the display and interpretation of facial expressions are – not unlike statistics – part of the many different ways of knowledge production that not only embellish but also constitute modern sport and its particular political potential.

Sociologist Tobias Werron has shown that the public comparison of performances is the decisive difference between modern sports and older forms of games, of ritualistic competitions, of occasional or spontaneous contests: A public beyond the audience in the stadium comments on the competition on a regular, and also somehow standardized, basis. The mediatized communication about sports (made possible in the 19th century through the combination of mass press and the telegraph) leads to the integration of the single contest into a continuous comparison of performances. 1

The single event, the present competition, the moving and fighting bodies only make up one half of modern sports, and they are in no way the more relevant or more essential half. The other half is the mediated comparison between performances that are separated by time and/or space. The talking and writing about sport in media is not an external representation of, or influence on, sport, it is a level of mediation that makes modern sports possible. 2 Thus, the visibility and comprehensiveness of the performance and the possibility to attribute the results to isolated components are of special importance. Sport is ruled by an ‘imperative of transparency’: Not only the result, but also the way the result is achieved should become evident. The standardizing of rules, the organization of leagues, the structure of the stadium, the gestures of the referees, the numbers on the jerseys of the players all aim at an augmented visibility and enhanced comparability – as do tables of leagues, statistics or slow motion replays. The media, from the start, define what can be recognized as a relevant aspect of a performance and an achievement.

The depiction and interpretation of faces, thus, are an essential part of media sport insofar as they contribute of the ‘imperative of transparency’ – to the definition, the comparison, and the explanation of achievements and performances. I will use a short example to elaborate on that: In television sport, a facial close-up very often follows a series of shots that depicted part of an ongoing competition. After seeing a foul or an offside we see the face of at least one of the players involved. The faces most times seem to display reactions to the events. Yet what is specific for media sports is that there is no clear action-reaction scheme; instead the typical sports live broadcast is a process of permanent revision, discussion, and reevaluation that takes place in the interconnection between images and commentary, between action, face and speech.

I here refer to German coverage of the final match of the Champions League in May 2006, between Arsenal London and Barcelona: In the first shot we see Thierry Henry receiving a long pass. The commentary refers to the pass as well as Henry’s technical ability: “… a nice pass … and how he takes it …” In the next shot we see Henry lose the ball to his opponent but then fight back, presumably by committing a foul – the referee at least blows his whistle. The commentator now has to revise his appraisal of the previous event. The third shot shows Henry in a kind of close-up, shaking his head in apparent disagreement with the referee’s decision. The next shot shows an instant replay of the man-to-man tussle between Henry and his opponent, now in a closer view. This is not only a repetition but at the same time a reevaluation of the earlier situation as well as a comment on the close-up on Henry, because it questions Henry’s evaluation of the situation. The commentary refers to the instant replay to come to the conclusion that Henry has committed a foul. Thus, while Henry’s face comments on the referee’s decision, the television commentary comments on Henry’s face by interpreting a slow-motion replay of his previous action. In this short example we first had a situation in which the commentator had to revise his own evaluation of Henry’s action and then a situation where he qualifies Henry’s evaluation of the referee’s decision.

It is important for this central status of the face that deciphering the facial expression is not only a feature of communication about achievements and performances, but also an operational part of the performance itself. While television tries to read the exhaustion and determination from the athletes’ faces it never misses the opportunity to emphasize that competing opponents do the same: Lance Armstrong looking in the eyes of Jan Ulrich before attacking him at the climb of L’Alpe d’Huez (Tour de France 2001) has become an often repeated icon of sports history, and stories of athletes judging one another, or their (feigned) injuries, by looking in each other’s faces are innumerable.

The human face in television sports, then, is always an object, as well as an instrument, of the process of knowledge production; it has to be scrutinized in slow motion and commented on to achieve public meaning. The face is a display that gives access to otherwise invisible aspects of the competition that can be physiological as well as psychological. In comparing the performances it becomes important to differentiate participants by the ‘transparency’ of their faces; in endurance sports like bicycle racing, for instance, it is quite usual to hear commentators talk about an athlete who is very ‘difficult to read’ because his face always looks strained, not just when he is in a tight spot.

On the one hand the visualization and interpretation of the face are totally integrated in the way knowledge is produced in television sports. They are connected to the physiological and psychological, to the quite complex technical and tactical features that differ in different sports and on different occasions. On the other hand the visualization and interpretation of the face can at the same time be connected to quite a lot more popular, broader forms of knowledge. The most frequent examples are psychological or biographical narratives in which the performance of players is connected to their lives outside of sports. The depiction of faces, thus, is symptomatic for three levels of ambivalence that are characteristic for modern media sport:

- The first level is the ambivalent relation between sports and media: The faces are part of the spectacle the media produces. Nevertheless, the faces are linked into the comparison of performances and are thus as much ‘performance itself’ as they are an embellishment thereof.

- The second level is the ambivalent relation between precise, operational knowledge and a kind of popular readability, i.e. between specialist discourses and interdiscourse. The face is scrutinized through regulated procedures and connected to psychological and physiological knowledge, but it is also an opportunity to articulate stardom, fandom, and the corresponding polysemic textuality. Not least through the depiction of faces, media sports becomes a field in which not only specialist discourses is shown to be relevant to the public, but popular knowledge can, conversely and quite operationally, also be applied to explain events. This process is quite fundamental for the integration of our highly specialized society as it is based on the division of labor.

- The third level is the ambivalent relation between on-field and off-field: During the competition the face of the athlete shows expressions that cannot be found elsewhere and thus define what sport is really about. At the same time, the faces – be they the athletes’, the coaches’, the fans’, or the cheering politicians’ – extend the sports into nearly any social or cultural field of relevance.

The politics of media sports has to be understood in this context. The body politics of sports quite often result from a naturalization but also a stylization of the body. Ethnic and gender differences are easily connected to the display of the athletes’ bodies, but the ‘facial politics’ are somehow more complicated. The ambivalent relation of the face to the body foster the connection of physical competition with so many other cultural meanings and modes of knowledge. In television sports the human is still a longing individual that can equally be interpreted (and finally understood) through scientific reasoning as well as common sense. The necessary hermeneutic process can strategically take up or avoid topics, and integrate as well as disintegrate different agencies. The nationalist ideas or the racist descriptions so omnipresent in sports can also be found in other media genres, if sometimes less clearly articulated. Specific for the genre of sports is the dynamic way these ideas can strategically be limited to ‘sport itself’ and at the same time consequentially be applied to common, general aspects of life – the interpretation of facial expression is on of the decisive procedures supporting this political potential of media sport.

Image Credits:

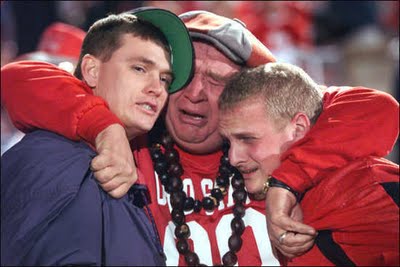

1. Fans crying after a loss

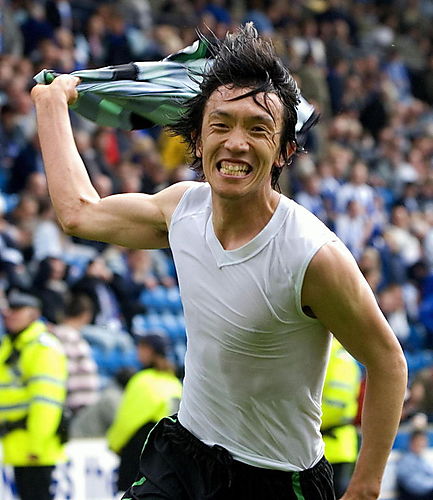

2. The thrill is evident on the face

3. Spanish soccer player Fabregas

4. Barcelona forward Thierry Henry

5. Front page image Lance Armstrong

Markus Stauff teaches Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam and is co-editor of the journal Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft. Main fields of interest are: Television Studies, Governmentality Studies, Politics of Media, Visual Culture of Sports. (http://home.medewerker.uva.nl/m.stauff/)

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: PHOTOS: The Hottest O Faces In Male Soccer / Queerty

Pingback: PHOTOS: The Hottest O Faces In Male Soccer | Sawatdee Network