Colombo Calling: Radio Ceylon and Bombay cinema’s “national audience”

Aswin Punathambekar / The University of Michigan

“I would never miss it. Every Wednesday, I would make sure I was near a radio set,” I remember my father saying. He would often tell me about his favorite radio show, Binaca Geet Mala, broadcast on shortwave by Radio Ceylon, a Colombo-based broadcasting company, during the 1950s. “His voice, it was like he was speaking to me,” he would say of Ameen Sayani, the renowned host of Binaca Geet Mala and other shows on Radio Ceylon and later, on All India Radio. I like to think that the stories about radio and Hindi cinema’s playback singers, music directors, and stars that I heard from my father and others in his generation have something to do with my interest in mapping Bombay cinema’s relationships with other media – radio, state-owned television (Doordarshan), cable and satellite television, and now, the Internet and the mobile phone. Imagine my excitement, then, when I got to meet Ameen Sayani in downtown Bombay last year, in the same office where he produced, each week, a show that captured the attention of millions across the Indian subcontinent. It is this story of my encounter with one of the most important figures in broadcasting and Indian film culture that I wish to narrate in this column as a way of raising from broader questions about broadcasting and film history.

Apart from brief mentions of radio as an important site for audiences’ engagement with film music, there is no sustained historical analysis of how broadcasting shaped the workings of film industry in Bombay. The story of film songs and broadcasting has been narrated mainly from the perspective of All India Radio and nationalist elites’ interventions in the realm of cultural policy.

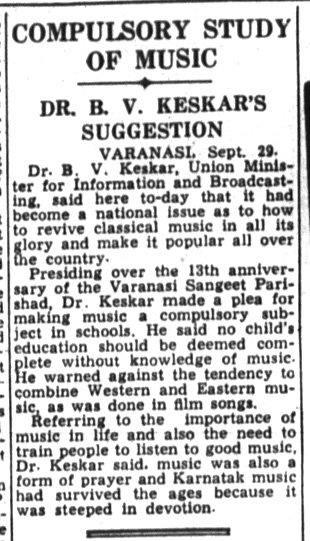

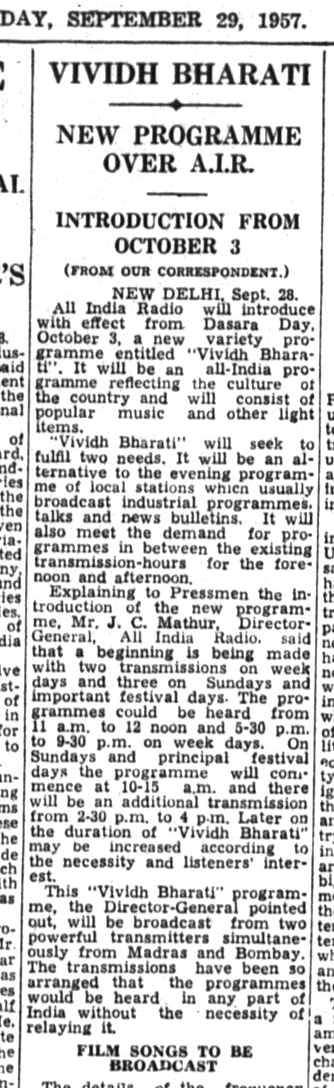

As the story goes, B. V. Keskar, minister of information and broadcasting from 1950-1962, deemed film songs ‘cheap and vulgar’ and effected a nearly complete ban on film songs1. While Keskar attempted to create ‘light music’ – with lyrics of ‘high literary and moral quality’2 and music that would steer away from the ‘tendency to combine western and eastern music as was done in Hindi films’3 listeners across India began tuning in to Radio Ceylon for film songs. As one oft-quoted survey of listener preferences noted, ‘out of ten households with licensed radio sets, nine were tuned to Radio Ceylon and the tenth set was broken’4. Recognizing the enduring popularity of film songs and acknowledging the difficulties involved in forging a new taste public, Keskar relented and on October 28, 1957, announced the launch of a new variety programme called Vividh Bharati that would ‘consist of popular music and other light items’5. The press release also pointed out that of five hours’ programming on weekdays, nearly four hours were dedicated to film songs.

This was, without doubt, a struggle over defining “national culture” and as Lelyveld points out, government controlled All India Radio was expected to play ‘a leading role in integrating Indian culture and raising standards’6. However, this narrative, in which Radio Ceylon makes a brief appearance, does not shed light on any other aspect of the film industry’s relationship with radio. How did producers, music directors, and playback singers react to All India Radio’s policies? How exactly did the overseas programming division of a commercially operated broadcasting station from Colombo establish ties with the Bombay film industry? What role did advertisers play? What was the production process for a hit-parade program like Binaca Geet Mala? In what follows, I draw on my conversation with Ameen Sayani to provide a brief account of Binaca Geet Mala and highlight Radio Ceylon’s role in forging a “national audience” around the songs and stars of Bombay cinema.

In 1951, Radio Ceylon established an agency in Bombay – Radio Advertising Services – in order to attract advertising revenue and recruit professional broadcasters who could record both commercials and programs. It was through this agency, headed by Dan Molina, an American entrepreneur who had lived and traveled across the subcontinent, that Ameen Sayani and a small group of producers and writers created a number of film-based radio programs including Binaca Geet Mala. Sponsored by a Swiss company named CIBA and broadcast using three powerful short-wave transmitters, Geet Mala was initially produced as a half-hour competition program in which seven random film songs were broadcast each week with audiences invited to re-arrange the songs chronologically. With a hundred rupees as the jackpot each week, the show attracted attention immediately and according to Ameen Sayani, ‘the very first program, broadcast on December 3, 1952, brought in a mail of 9000 letters and within a year, the mail shot up to 65,000 a week.’ Recognizing the difficulties of the competition format, Sayani and other producers decided to transform Geet Mala into a one-hour hit parade in December 1954.

While continuing to encourage audiences to write in with song requests, CIBA, after consultations with their sales personnel, identified 40 record stores across India that would send weekly sales reports to be used as the basis for the countdown show. However, when it became clear that some film producers and music directors were involved in rigging record sales, Geet Mala producers decided to set up radio fan clubs across the country as a “popular” counterweight. As Sayani explained,

We used to get letters from avid listeners, and some of them used to say, we are listening to your show along with our friends. And our letter went back saying if you are listening with your friends, why don’t you form a club? Give your club a nice name and if you have the funds, type up a letterhead or at least have a rubber stamp. Get people together at one place to listen, if you can, otherwise figure out two or three places where people can congregate and listen. Then send us, every week, your top songs so that we can play the songs you have chosen. And they responded. At the peak, we had 400 radio clubs all over India.

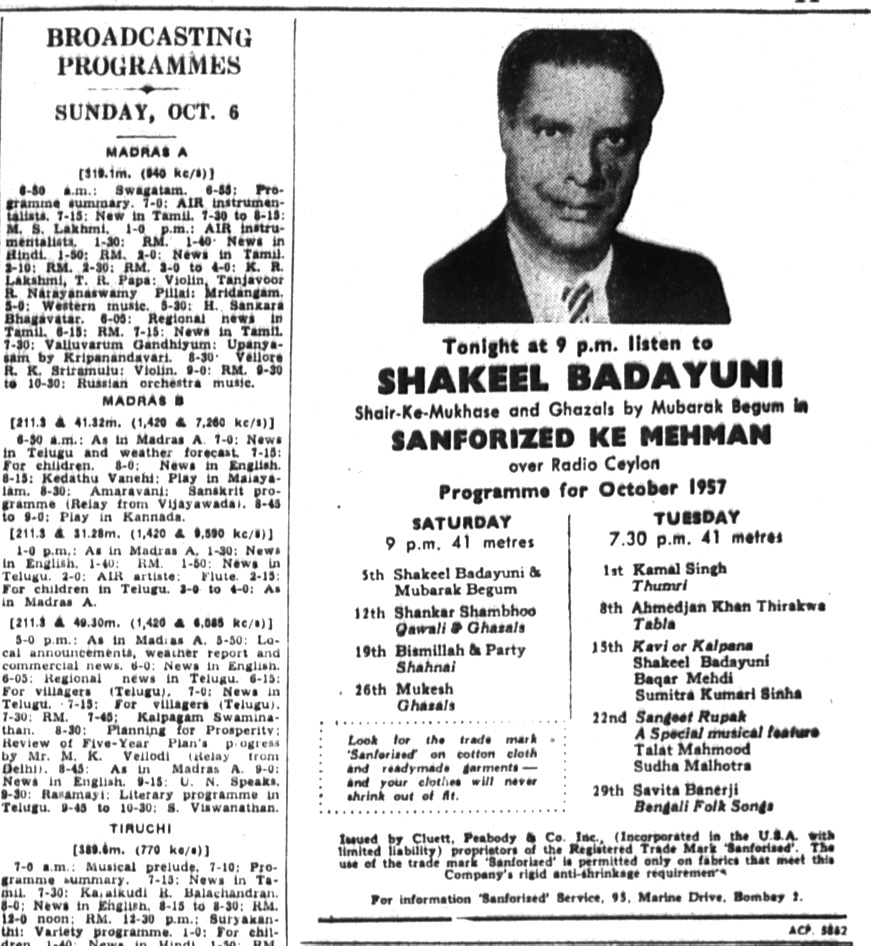

Each week, representatives from CIBA would collect sales figures and fan letters and develop a countdown that Ameen Sayani would use to produce a show. Each week’s show, recorded in Bombay, would be flown to Colombo and broadcast from 8:00-9:00 pm on Wednesday and as Sayani reminisced, “the streets would be empty on Wednesday nights…in fact, Wednesdays came to be known as Geet Mala day.” While the relationship between radio programs, the routines of daily life in independent India, and ongoing struggles to define “national culture” certainly merits in-depth analysis, I wish to draw attention here to the ways in which the film industry became involved with Geet Mala.

The overwhelming popularity of Geet Mala led to complaints from music directors when their songs did not feature in the weekly countdown, and as Sayani explained, “some came to CIBA to say that something fishy was going on and they were losing business.” In response, CIBA’s representatives invited film producers and music directors to go through the sales figures and registers, and Ameen Sayani suggested appointing an ombudsman from the film industry who would check the countdown list. With established figures like G. P. Sippy and B. R. Chopra assuming this role, producers and music directors seemed satisfied with the process and according to Sayani, information regarding record sales and popularity among audiences in different parts of the country began circulating in the film industry. By the mid-1950s, directors and stars from the film industry were participating in weekly sponsored shows on Radio Ceylon and film publicity quickly became a central aspect of Radio Ceylon’s programs. As Sayani recalled, “no film was ever released without a huge publicity campaign over Radio Ceylon and later, Vividh Bharati.” Radio, in other words, provided film stars, directors, music directors, and playback singers with the opportunity to both listen, speak to, and imagine a “national audience.”

I do not wish to suggest that the picture of the “audience” that radio shows provided the film industry carried greater weight than box-office considerations and the information that producers, directors, and stars in Bombay received through distributors. What I am arguing for is a consideration of radio’s role in making the films, songs, and stars of Bombay cinema a part of the daily life of listeners across India, creating a shared space for listeners in locations as diverse as the southern metropolis of Madras and a small mining town like Jhumri Tilaiya in the northern state of Bihar, binding together the nation-as-audience, and enabling the Bombay film industry to imagine a “national audience.” Furthermore, this story of radio and film also encourages us to ponder how other developments in media and communications – for e.g., satellite television and the emergence of powerful media companies such as the London-based Eros International – influenced the circulation of films and film music, reconfiguring the Bombay film industry’s spatial coordinates and engendering new sites and forms of consumption. This does not necessarily mean that we think only about continuities from the 1950s to the present. Rather, this story opens up a space for more grounded explorations of the inter-woven histories of different media technologies and institutions in Bombay.

Image Credits:

1. The Hindu, September 29, 1953

2. The Hindu, October 3, 1957

3. The Hindu, September 29, 1957

- Lelyveld, D. (1995) ‘Upon the Subdominant: Administering Music on All India Radio,’ pp. 49-65 in

Carol Breckenridge and Arjun Appadurai (eds) Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [↩] - Awasthy, G C. (1965) Broadcasting in India. Bombay: Allied Publishers, 51. [↩]

- The Hindu (1957) ‘Compulsory Study of Music,’ September 29. [↩]

- Lelyveld, D. (1995) ‘Upon the Subdominant: Administering Music on All India Radio,’ pp. 49-65 in Carol Breckenridge and Arjun Appadurai (eds) Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 59-60. [↩]

- The Hindu (1957) ‘Vividh Bharati: New Programme Over All India Radio,’ September 29. [↩]

- Lelyveld, D. (1995) ‘Upon the Subdominant: Administering Music on All India Radio,’ pp. 49-65 in Carol Breckenridge and Arjun Appadurai (eds) Consuming Modernity: Public Culture in a South Asian World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 57. [↩]

Aswin,

Really interesting piece. Makes me think of my own relationship with Radio including my first memories of filmi music– given the size of our living room radio I actually thought that Lata Mangeshkar lived inside it. (i was very young, ofcourse). My dad talks about how in his student years at Benares Hindu University, the street radio would become the favorite add of the college students creating a youth culture engendered through consumption cultures (eating out, smoking, watching films for example) in masculinized public spaces. The figure of Lata Mangeshkar is especiallly interesting to me, in imagining a national audience.

Thanks, Madhavi. I love the idea of Lata Mangeshkar living inside the radio! And if anything, your comment underscores the need for accounts of radio and daily life. All we have at this point are bureaucrat-written histories of All India Radio and a handful of scholarly articles focused on the more “political” aspects of radio in the subcontinent.

My father is the Dan Molina you spoke of in the article. He gave both Sayanis their start. Binca Geet Mala was his brain child. He loved radio all of his life.

Hi Mimi – I’m thrilled, as you can imagine, to see your comment here! And I’d appreciate an opportunity to chat with you. Pl let me know.

Dear All,

!!!Greetings!!!

I used to listen Sh. Amin Sayani on Radio Cylone in my childhood. His programme ” Cibaca Geetmala” has made a special place in my heart.

Now, I am 40 yrs and want to relive those moments by listening this programme. Could anyone provide the recordings of ” Cibaca Geetmala” and other programmes in which Sh. Amin Sayani has given his golden voice.

I shall be really grateful.

With regards,

S.K. Chitra

INDIA

M- 9871643667

I sang along with Laurie Lopez (somwhere in 1964-65) an Everly Brothers number “Bye Bye Love” on Cadbury Amateur Hour Amin Sayani compere, and the clip was played again on Radio Journal on Thursday following. Is it possible to get a recording of the same.

Thanks

Allan

Pingback: Bollywood & the “new media” question « BollySpace 2.0