How Not to Format (or, What the Global Format Trade Could Teach Tim Gunn)

by: Tasha Oren / University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee

Format television most often depends on unscripted interactions nestled within rule-defined sequences and set-piece locations: the game show, the “life-in-bubble” elimination, the makeover, the cook-off. Globally, television’s increased reliance on the format has grown so commonplace as to make up its own TV universe, existing peaceably with TV’s other universe of elaborately-structured, long-form narratives.

Indeed, the two trends are easily thought of as opposing impulses: the dazzling complexities of narrative possibilities (that play not only with multiple storylines but also through reconfigurations of the episode and season as flexible temporal units) versus the repetitive protocols of format television. Further, the growth industry of global format trade is all about paring down to content-containers: a set of formal, modular “rules” or codes. It is these codes (the format “engine”) that are traded (and borrowed, and stolen) across television systems. And, it is these rules that make each iteration familiar.

The storytelling possibilities of much of contemporary television were eloquently addressed on this site and elsewhere. But what of the evolving format? Are there particular critical tools useful for judging the delicate alchemy of rule-bound systems and repetitive custom-procedurals of tasks, ritualized judgments, nerve-fraying time-constraints, and the Great Reveal (transformation/elimination)? What’s “good” in good format TV?

Global formats depend on the most televisual of principles: formulaic repetition and familiarity. One common way of thinking about code and content is global rules and local adaptation. Examples of such local adaptation abound in writings about global reality shows like Big Brother or Pop Idol around the world. These shows are instantly recognizable to any viewer familiar with the rules, yet the content has the feel of the local, and the program, as one Australian format devisor has termed it, plays out a “parochial internationalism.” Whether the dominance of global TV formats is evidence of globalized homogenization of culture or the assertion of national locality has taken up the bulk of critical debate. But one aspect I’d like to take up here is that global formats are about the modular logic of television—the basic “innovation within convention”—and that audiences know and understand formats’ inherent mobility. Formats must, in order to work, demonstrate a satisfying complimentary relationship between code and content, rules and what happens within them. And all this brings me to Tim Gunn.

Co-hosts Tim Gunn and Veronica Webb

One of the striking TV failures this fall is Tim Gunn’s Guide to Style. For Bravo, Gunn’s makeover format show (coinciding with the release of a style book authored by Gunn) was no-brainer TV gold. Tim Gunn—the thoughtful intermediary between competing designers and judges on Project Runway—had emerged as the undisputed star of the hit designer competition format. The show would premiere to a built-in audience, a retail tie-in, a thriving all-things-Gunn internet portal and so much spin-off sheen (including appearances from Project Runway personalities). Further, Gunn’s approach (and book)—emphasizing process, lists and rules—seemed tailored to format-making.

Project Runway Season 3 cast

Built on the engine of the BBC format What Not to Wear (adapted in the US by TLC ), Gunn’s version (co-starring former model Veronica Webb) highlights rules (the four piles of closet-binging, the 10-item shopping list) but further codifies the format’s basic structure of analysis/purge/lesson/shopping/reveal with yet another overlapping structure that further names (and graphically identifies) each stage. Among them are:

The contract (in which the self-nominating woman is urged to commit to change):

The closet purge:

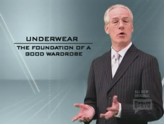

The underwear inspection (yes, the Gunn rulebook stresses the importance of “foundational garments”):

The consultation (Gunn uses a computer-generated image of the participant’s figure to illustrate rules of fit):

A visit to a “life coach”:

An upscale lingerie shop, the shopping spree:

The gift cabinet (each woman is presented with a product-placed gift, fetched elaborately from a set-piece cabinet):

The makeover:

And, finally, the Reveal, where friends and family enact the makeover format’s money shot, the tearful fashion show:

Following its debut in September, television critics were politely dismissive. In posts, blogs and discussions sites, viewers were unusually unanimous in their disappointment, first professing admiration for Tim Gunn and then pronouncing the show a thin, soporific gruel. After only four episodes, Bravo put the show on hiatus and, as of this writing, has no clear plans to air the remaining season.

The utter failure of the show to generate excitement, Bravo’s squandering of one of their best assets, and the format’s complete inability to speak to the network’s base offer one pathway into understanding the format universe of lifestyle TV and what about the formulaic works. There is plenty to explain the show’s inability to deliver televisual pleasure: the too-tight mechanics of segmentation, the enervating, matched coolness of Gunn and Webb, the self-conscious politics of class and borough clash, the relentless sameness of advice; in these and more, the show is instructive in—to use Gunn’s own oddly obsessive attachment to undergarments—illustrating the foundations of format success.

The Gunn 10-item shopping check list

Since all format television is recombinant, and increasingly depends on the audience’s contextual and layered understanding of its conventions, what makes certain format adaptations work is largely the fit between general protocol (the “rules” and structural logic of each text) and the specifics at play.

The show fails in skewing the ratio of code to content: successful global formats’ elaborate content is enabled by a set of simple rules. In contrast, Tim Gunn’s Guide to Style is so thoroughly overburdened by tight protocol as to nearly close down variation or tension. Thus, many fans’ most memorable moment has been one participant’s horrified refusal to submit to an underwear inspection. With no built in elasticity, such pushback results in breakdown. An audience skilled in format reading enjoys the play made possible by the rules, not their clockwork efficiency.

Another important aspect of the format as a modular unit of television programming is that it often travels as an iteration, rather than an original text. Indeed, much of the (academic) fascination with Big Brother, Survivor, Who Wants to be a Millionaire? or So You Think you Can Dance has been their proliferation and various global incarnations. The format, after all, is an open recipe, a system of rules designed to produce particular—although preferably not entirely predictable—effects. Most importantly, it is not a tabula rasa, as viewers and participants draw on collective conventions of the format to read its present iteration. Thus, Gunn’s show was read by viewers as such a version, not merely of “makeover” shows but a “what-not-wear” iteration, Bravo-style. Unlike critics, viewers were not so much disappointed that the show’s format was familiar but in that Bravo and Gunn were unable to work the format—its celebrity host retreating into a staid instructor role, with the participant as star. In format, originality of form hardly matters; how rules enable character and conflict is content.

Most significantly, however, the show fails in addressing its locality—a cardinal tenet of format television.

In the emerging body of TV scholarship about global formats, persistent attention is paid to local iterations as expressions of national identity and cultural specificity. I’d like to stretch (shrink, actually) the locality approach to the U.S. case and the inter-network articulation of specificity to suggest that one reason for Tim Gunn’s Guide to Style‘s failure is its lack of Bravo native-ness.

Like globally distributed formats that seek to articulate local “takes” on global formats, inter-network formats in the U.S. case can also be understood as local iterations. For TLC’s populist appeal, the What Not to Wear format’s casual emphasis fit the network’s overall address, yet Bravo’s location on the psychic dial clashed with its iteration’s balance of code and content. The tight protocol of scheduled activities and responses allowed the show’s style-challenged participants precious few moments to be anything but compliant, while Gunn and Webb’s instruction and determinedly backseat approach highlighted the ordinary fashion woes of these straight, bridge-and-tunnel middle-class women, insisting that they, not the show’s urbane hosts, were its principle actors.

Clinton Kelly and Stacy London of TLC’s iteration of What Not to Wear

Gunn as Bravo native

And with plastic hangers

The successful format is nothing if not culturally elastic, yet articulation of location and audience-identity largely determine its ability to travel. Learning from Tim Gunn, the “local” that modifies the global of television can be more than just geographical.

Image Credits: Images supplied by author.

Please feel free to comment.

Tasha – I’m really glad that you decided to take on Tim Gunn’s ill-fated show, and why it so completely doesn’t work, before it disappears entirely from our collective pop memory. It’s a stunning example of a failure of “format TV,” not only because it failed to register with audiences, but also because Bravo hyped this show beyond belief in the months before its premiere. (Were they trying to compensate for something?) One might say we can even learn more about how format TV works by analyzing a failure than one of the innumerable (and, personally, in the case of “Dancing with the Stars,” absolutely puzzling) successes.

The idea of Bravo as location is also quite interesting; exec Lauren Zalaznick is pretty transparent about developing a suite of shows that all work together. Here’s a quote from a memorable “New York” magazine story:

“She says that what crystallized Bravo’s programming philosophy for her wasn’t Project Runway so much as Bravo’s previous smash hit, Queer Eye. “We had to define what pop culture meant on Bravo,” says Zalaznick. “And what pop culture, as defined by us, has come to mean is five affinity groups: fashion, food, beauty, design, and pop. It’s not coincidental that the five guys in Queer Eye each represented one of those things.”

(http://nymag.com/news/features/35538/)

Which brings me to Queer Eye — I wonder why that show, which also featured a team of hosts going into someone’s home and basically tearing it apart, as well as a quite stringent protocol for its weekly particpants, was such a runaway hit? Perhaps because, as you point out, the participants took a back seat to the (purposely queer-caricatured) hosts? Is there a culturally embedded difference between entering a straight man’s home and tearing apart his “style” and going into a woman’s home and rifling through her underwear? Is it just that Gunn and Webb aren’t funny? I’m inclined to think it’s a combination of all those and more.

And, on another note: *SO* excited for Project Runway 4!