Borat In (Next To!) The Balkans

by: Daniel Marcus / Goucher College

The Borat film has become a fixture at the multiplex in Ljubljana's biggest mall since its opening coincided with the American release. (Ljubljana is the capital of Slovenia, the richest and northernmost of the former republics of Yugoslavia. Turn east from Venice, cross the Adriatic, and you end up in Slovenia. It is a member of both NATO and the European Union.) Sascha Baron Cohen has made a successful promotional trip in character to the neighboring Croatian capital of Zagreb and was featured prominently on one of the Croatian national news programs. The former Yugoslavia has caught Borat fever.

Given that Borat plays off ricocheting notions of national and cultural identity among Americans and non-Americans, watching the Borat phenomenon from another country provides the opportunity to explore one region's take on Americans and transnational interactions. For those in the former Yugoslavia, Borat offers a rich field of representations to express and explore their self-definitions as emerging participants in Western culture and social practices, and to establish their difference from (read: superiority over) other societies that have not merged to the same extent with Western economies, political associations, and popular culture. At the screening I attended, the mostly young audience started laughing from the first shots of Borat's hometown. Their laughter indicated that in their minds, their own circumstances were comfortably distant from the dilapidated rustic scene. Most Slovenians grew up in small to medium-sized towns, and the architecture of the “Kazakhstani” town bore some basic similarity to Slovenian housing, given that the depicted village is actually in Romania (though Slovenian villages are much more prosperous). To the Slovenian audience, however, the backwardness of the village circumstances were cues for derisive laughter. When I asked college-age fans if the audience was aware that the village was actually European, they replied that it didn't matter – that to Slovenians, both Kazakhstan and Romania were “the East,” meaning backward, unsophisticated societies, where seeing cows in the living room should be no surprise. (Of course, Kazakhstanis have registered objections to such notions of their own increasingly wealthy country.)

Indeed, to some Slovenians, the joke would work if the rustic scenes were said to be even in neighboring Croatia, because to them, the rest of the former Yugoslavia qualifies as the East. This feeling seems to be stronger among younger people who never experienced feelings of solidarity with fellow Yugoslav citizens in the pre-1990 era, and who take their attitudes from the more prominent European countries. In European thinking, the Balkans are often associated with ethno-religious feuding and hatred, unreconstructed male chauvinism, unpredictable and overemotional behavior, lack of cultural sophistication, and economic deprivation. Enjoying the film's snipes at rustic rubes is a self-affirmation by Slovenians that THEY couldn't possibly be the ones being laughed at; they can assume the superior position of the Western (and, in the symbolic schema of the region, therefore non-Balkan) viewer that the film constructs at its beginning. Judging from the warm welcome Borat received in Croatia, the Croatians also use the film to affirm their position as Western, no matter what the Slovenians may think; as one of the Slovenians I talked to put it, each country in the region likes to think that the Balkans start just beyond its own southern or eastern border.

This affirmation of distance from the backwardness the film depicts is telling, given that the figure of Borat actually bears strong visual similarity to previous generations of Balkan men. Early versions of Borat in Baron Cohen's act hailed from Albania and Moldova. The anti-Gypsy attitudes of the character also coincide with Balkan social reality. Assuredly, to most Americans, Borat might as well be from the former Yugoslavia – the jokes would work the same to American audiences. In Borat, however, the distance of the character's sophistication from the self-conception of the audience here means that the possibility that Baron Cohen is using Kazakhstan as a stand-in for their own homeland is not even considered.

Of course, Kazakhstanis are not the only nationality that Baron Cohen victimizes in Borat. He skewers American attitudes with even greater discursive power, given that the portraits of foolish Americans are presented as something approaching real-life encounters. For Slovenians, this provides a double movement of superiority and derision; they can feel superior to the clueless Kazakhstanis, and to the equally clueless Americans. The stupidity of Americans presents itself in two distinct though related forms. First are the racist and homophobic comments that Borat elicits, which some Slovenian fans identified as the strongest parts of the film. While some audience members professed awareness that the ugliest comments were cherry-picked for comedic or political purposes, the responses fit too well with Slovenian (or, at least, young, urban, Slovenian) conceptions of American attitudes to be discounted significantly. As one student put it, the infamous South Carolina frat boys corresponded to his image of typical American collegians – “fat, ignorant, and racist.”

Secondly, the idea that the Americans were taken in by Baron Cohen, that they would actually find Borat to be believable in his ludicrous opinions and apparent ignorance of Western social practices, was proof of Americans' own ludicrous understanding of the rest of the world. While Slovenians might enjoy exaggerated scenes of Eastern squalor, they would also believe that anyone who was educated enough to have a job as a reporter, who dressed in a Western suit and was generally competent in English, would necessarily be familiar with ubiquitous media images of American society and culture and would act in accordance with Western norms. Because some Americans took Borat's ridiculousness seriously, Borat confirms suspicions that Americans are profoundly heedless of the realities of global culture. Indeed, when “Borat” was interviewed on Croatian national news, the reporter played along as if Borat were a genuine reporter, while simultaneously winking at her audience that she was doing so only to further Baron Cohen's entertainment and promotional agendas. In so doing, she established her superior knowingness to those American newspeople and interview subjects who were taken in by Borat's persona.

In the Croatian interview, Borat steered clear of the anti-Semitic attitudes that feature heavily in the film, but he indulged in a couple of Gypsy jokes, to the enjoyment of his television host. Baron Cohen straddles that tenuous line between exposing racism and sexism through humor and using racist and sexist attitudes to make his jokes work. Slovenian fans stated that they felt confident that Slovenian audiences would laugh at the anti-Semitism displayed in the film, rather than with it, because anti-Semitism is not particularly active in the national culture (and perhaps because some may know Baron Cohen is Jewish). They also asserted that they laughed at the anti-Gypsy attitudes, but could not be so confident that other audience members were laughing at those remarks rather than with them. The Roma community in Slovenia constitutes the most put-upon, least assimilated, and poorest minority in the country, and a recent outbreak of anti-Roma protests and violence, resulting in the displacement of one community from its homes, has sparked the biggest political controversy since a conservative administration took office two years ago. Anti-Roma attitudes pervade the region, and in the Croatian broadcast at least one of the Baron Cohen's jokes registered as more anti-Gypsy than anti-prejudice. American audiences may be able to enjoy Borat's anti-Gypsy comments as so distant from American realities as to be harmless or quaint, as well as ugly, but no such distance is possible here. Of course, that can also mean that some of the comments can be more effective in Slovenia in exposing the logic of anti-Roma prejudice. It also creates an even greater impression of American racism, because Americans' muted reaction to the character's anti-Gypsy rants are taken here as powerful evidence of anti-minority feelings, rather than as befuddlement or polite neglect of irrelevant foreign nastiness.

Slate's Dana Stevens wrote that, ultimately, the only group who should really be insulted by Borat is fat people, and the wrestling match did get the biggest immediate reaction from the multiplex crowd of any scene in the film. In the Slovenian context, however, the true target of the film's ire is the American people in the Age of Bush, while the film is also useful in furthering Slovenian feelings of belonging to the advanced civilization of Western and Central Europe (a civilization that has produced, in Baron Cohen's act, the British dimwit Ali G and Austrian fashion slave Bruno). Do American Blue State viewers (a recently expanded category!) exhibit the same attitude toward the Southerners and Westerners in the film as Slovenians do to representations of Kazakhstan? Is enjoyment of those scenes inextricably connected to the felt distance from the behavior displayed? Indeed, is the assertion of distance the most meaningful pleasure we can produce from such scenes? Baron Cohen lets Southeastern Europe off the hook by using Kazakhstan as Borat's homeland; in Slovenian eyes, no Americans are afforded the same kind of comfort, for we are all generally implicated. And it will take more than one election to change that.

Image Credits:

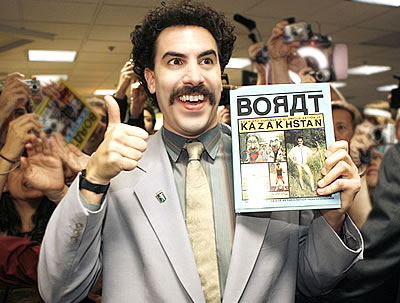

1. Borat success

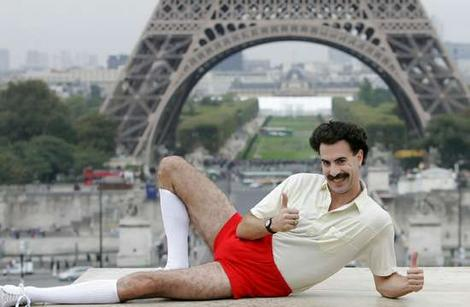

2. Borat

3. Sascha Baron Cohen, “Borat”

Please feel free to comment.

ugly Americans at home

While I understand why the wrestling scene might be in some ways the most universally insulting, I was perhaps most taken aback during the scene at the dinner party. As I said to the person with whom I’d gone to the movie — I’m embarrassed for everyone involved in this situation, including myself, the other people in this theatre, and everyone on screen.

Most interesting to me were the places that the film actually did make people seem nice. The couple running the Bed and Breakfast seemed genuinely kind; the prostitute seemed like someone scrambling to get by like anyone else. I wonder why exactly these particular subjects were let off the hook. In the case of the bed and breakfast owners, I’d assume because it helps ensure that the film isn’t perceived as actually anti-Semitic, as the only “real life” Jewish people in the film are well-meaning and gracious.

The film does work to expose a lot of ugly thinking on the parts of Americans who are ignorant of and sheltered from the realities of “foreign” cultures and people. However, while the film works at this level when played outside the United States and when shown to certain audiences in the U.S., do those people caught with their racist, homophobic, misogynistic pants down ever get that they are the butt of the joke? I’d assume that the South Carolina fraternity brothers (who are involved in a lawsuit over their portrayal) got it. But, did the majority of these people? I just wonder how effective the “lessons” here are for the participants who appear to be most in need of schooling.

Irony in Borat

I agree that there IS a danger of subtle ironies being lost on those for whom such ironies are ultimately constructed, but in these exposures (in all their unrestrained vulgarity) are indeed effective lessons.

However, for me, the film is not educating those who are ignorant, but those who are ignorant of this ignorance: the supposed “tolerant” cinema-goers.

Is not the shock of Borat that such blatant hatred still exists in a “free and multicultural society”? Indeed, could we not see in “Borat” an illustration that whilst we continue to go on imagining that we live in a society free from ignorance and hate, we really have just learned to sublimate them?

The irony of the frat boys’ law-suit is that it is not the influence of a fantasmatic, out-of-context situation that they found themselves in (as a result, they argue, of encouragement and alcohol), but precisely the opposite: it is the REMOVAL of the P.C. fantasy framework that has been built up around Western socialism that confirms this fantasmatic framework within which we all operate.

In short, the true irony of Borat lies in the “superior feeling” of those people who watch Borat in the cinema with both mocking and an unconscious relie: that it is not they who are caught out with his revelatory guise.

on Borat/Slovenian perception

I enjoyed reading the article. But being a Slovenian I have to say that the author of the article misinforms and generalizes about life in Slovenia – just as authors of Borat have done about life in Kazakhstan. And yet, one more time (as the authors of Borat have done), presents one nation (this time Slovenian) as the one who is rather reckless – although I am sure this was not his intent. I sincerely believe people should try to experience a different cultural environment as deeply as possible and look from the constructive perspective instead of the destructive, negative side that serves to nothing (except to self-aggrandizement). Afterall everything in the world exists for a reason – and that goes for peoples’ habits as well. Unfortunately the article is yet another generalized and rather negative presentation of a nation, which – furthermore includes incorrect data(for example: neither me, my parents nor my Slovenian friends have ever lived in a village or a house similar to Borat’s – although I am sure it could/would be a lot of fun :)). And for the end – I think we should finally realize that there is a good/positive side to everything and start respecting other nations and their habits just as much as we would like our’s (ours) to be respected. People from less developped countries are often happier that people from the West – aren’t they then the only ones, who could feel superiour? Afterall, happiness is all that matters at the end, isn’t it?

America = Eastern Europe

When I first watched the movie Borat in theaters, I was immideately fascinated by how ignorant Americans are about other cultures. I cannot myself say that I know anything about Kazakhstan or even where it is located on the map, but watching the “Fat Americans” unknowingly admit to their racist, homophobic, and misogynistic tendencies was a little disheartening and that Americans in general do not know anything about distant cultures. What is interesting about this article however is that Slovenians seem to have similar sudo-racist thoughts as well. The Slovenians feel “superior” to the Kazakhstanis just as the whites once thought they were “superior” to the blacks. It seems that even though american slavery is the most well known and infamous of bigot behavior in the last 200 years, and that the world still thinks of us in that way, it still exists in those countries that we percieve as “over to the east somewhere”.

Humans Will Be Humans

Given the artistic merit that performers are allowed, Daniel Marcus comments on how Sascha Braon Cohen’s universally comedic character, Borat, puts himself in politically incorrect circumstances and thus is able to produce counter hegemonic comments on society. I find it fascinating that this notion carries over seas onto the Eastern Hemisphere. Most Americans are made to believe that other areas of the world are much more open-minded, when this article proves that that is not the case at all. I feel as though Borat, though intended primarily as a comedic enjoyment plays off of society’s hegemonic values and social norms and forces us to see not just American ideals, but the universal authentic human perspective.